H. P. Lovecraft spent most of his adult life in genteel poverty, slowly diminishing the modest inheritance that had come down to him from his parents and grandparents. He had no cash to spare on expensive gifts for his many friends and loved ones. So Lovecraft was generous with what he had—time, energy, and creativity. While not religious or given to mawkish displays, when it came to Christmas, Lovecraft poured his time and energies into writing small verses to his many correspondents, a body of poems collectively known as his “Christmas Greetings.”

Yesterday I wrote fifty Christmas cards—stamping & mailing them before midnight. Only a few, of course, had verses—& these were all brief and not brilliant.

H. P. Lovecraft to Lillian D. Clark, 23 December 1925, Letters to Family & Family Friends 1.511

Most of these verses do not survive. They would have been written on cheap Christmas cards, which were seldom preserved. Those that survive are mostly attested in drafts that survive among Lovecraft’s papers, or more rarely in a letter where he copied a few verses to share with someone else (LFF 1.511-515). Most of them are not pro forma verses, the same rhyme copied for each recipient, but are uniquely tailored for their recipient, a reflection of their shared history and correspondence with Lovecraft.

In looking at Lovecraft’s Christmas Greetings to his women correspondents, we catch a glimpse at Lovecraft’s thoughtfulness. Their response, unfortunately, is often lost to us; though some few of them certainly responded in kind. We know Elizabeth Toldridge, for example, wrote her own Christmas poems to Lovecraft, because at least one survives.

To Lillian D. Clark

Enclos’d you’ll find, if nothing fly astray,

Cheer in profusion for your Christmas Day;

Yet will that cheer redound no less to me,

For where these greetings go, my heart shall be!

The Ancient Track 330

Six poems to Lovecraft’s elder aunt survive. Probably he began writing these to her as a child. Probably too this was one of the later verses, when an adult Lovecraft spent Christmases in New York, and his Christmas greetings would be sent by mail instead of delivered by hand. Though Lovecraft might travel as widely as his finances permitted, and visit friends far away, yet his heart was ever in Providence, Rhode Island—and his family there.

To Mary Faye Durr

Behold a wretch with scanty credit,—

An editor who does not edit—

But if thou seek’st a knave to hiss,

Change cars—he lives in Elroy, Wis.!

The Ancient Track 314-315

One poem survives to Mary Faye Durr, president of the United Amateur Press Association for the 1919-1920 term, and refers to amateur journalism affairs. The “knave” in this case was E.E. Ericson of Elroy, Wisconsin, who was the Official Printer for the United.

To Mr. and Mrs. C. M. Eddy, Jr.

Behold a pleasure and a guide

To light the letter’d path you’re treading;

Achievements with your own allied,

But each the beams of polish shedding.

Here masters rove with easy pace,

Open to all who care to spy them,

And if you copy well their grace,

I vow, you’ll catch up and go by them!

The Ancient Track 328

One poem survives to the Eddys. They were friends from Providence before Lovecraft eloped to New York in 1924, and Lovecraft would revise or collaborate with Clifford Martin Eddy, Jr., and his wife Muriel E. Eddy would write several memoirs of Lovecraft in later years, chiefly The Gentleman from Angell Street (2001). While it isn’t certain, this letter probably refers to C. M. Eddy, Jr.’s efforts to embark on a career as a writer (“the letter’d path”).

To Annie E. P. Gamwell

No false address is this with which I start,

Since the lines come directly from my heart.

Would that the rest of me were hov’ring night

That spot where my soul rose, and where ’twill die.

But since geography has scatter’d roung

That empty shell which still stalks on the ground,

To Brooklyn’s shores I’ll waft a firm command,

And lay a duty on the dull right hand:

“Hand,” I will broadcast, as my soul’s eyes look

O’er roofs of Maynard, Gowdy, Greene, and Cook,

Past Banigan’s toward Seekonk’s red-bridg’d brook,

“To daughter Anne a Yuletide greeting scrawl

Where’er her footsteps may have chanc’d to fall,

And bid her keep my blessings clear in view

In Providence, Daytona, or Peru!”

The Ancient Track 327

Five poems survive to Lovecraft’s younger aunt, of which this is the longest—a Christmas greeting sent from New York, because Lovecraft was not in Providence to spend Christmas with her. The reference to “Daytona” references Anne Gamwell’s own trips to Florida.

To Sonia H. Green

Once more the greens and holly grow

Against the (figurative) snow

To make the Yuletide cheer;

Whilst as of old the aged quill

Moves in connubial fondness still,

And quavers, “Yes, My Dear!”

May Santa, wheresoe’er he find

Thy roving footsteps now inclin’d,

His choicest boons impart;

Old Theobald, tho’ his purse be bare,

Makes haste to proffer, as his share,

Affection from the heart.

The Ancient Track 326-327

Four poems to Sonia H. Greene, who in 1924 became Lovecraft’s wife, survive. This one dates from after their marriage, but during a period when they were separated and unable to have Christmas together (“Thy roving footsteps now inclin’d”). Broke (“his purse be bare”), Lovecraft offers the only thing to Sonia he can: his love.

To Alice M. Hamlet

May Christmas bring such pleasing boons

As trolldom scarce can shew;

More potent than the Elf-King’s runes

Or Erl of long ago!

And sure, the least of Santa’s spells

Dwarfs all of poor Ziroonderel’s!

The Ancient Track 326

Three poems to Lovecraft’s fellow-amateur journalist Alice M. Hamlet survive. She is best-known for introducing H. P. Lovecraft to the works of Lord Dunsany, and this Christmas Greeting contains explicit references to Dunsany’s novel The King of Elfland’s Daughter (1924), such as the witch Ziroonderel and the land of Erl—and there is a slight joke comparing Santa in this context, as Clement Clarke Moore had famously described him as “a right jolly old elf” in “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (1823).

To Winifred Virginia Jackson

Inferior worth here hails with limping song

The new-crown’d Monarch of Aonia’s throng;

And sends in couplets weak and paralytick,

The Yuletide greetings of a crusty critick!

The Ancient Track 317

Two poems to Winifred Virginia Jackson, Lovecraft’s fellow amateur-journalism and literary collaborator, survive. The Aonian was an amateur journal, while Lovecraft was serving as head of the department of public criticism.

To Myrta Alice Little

Tho’ Christmas to the stupid pious throng,

These are the hours of Saturn’s pagan song;

When in the greens that hang on ev’ry door

We see the spring that lies so far before.

The Ancient Track 317

Not every Christmas Greeting was unique; in some cases Lovecraft sent identical (or near-identical) verses to multiple correspondents. So for Myrta Alice Little only one Christmas greeting survives, which was also sent to Winifred Virginia Jackson, Verna McGeoch, and Alfred Galpin—and the sentiments echo the opening to “The Festival,” where Lovecraft is less interested in the Christian ideology than the pagan roots of the holiday.

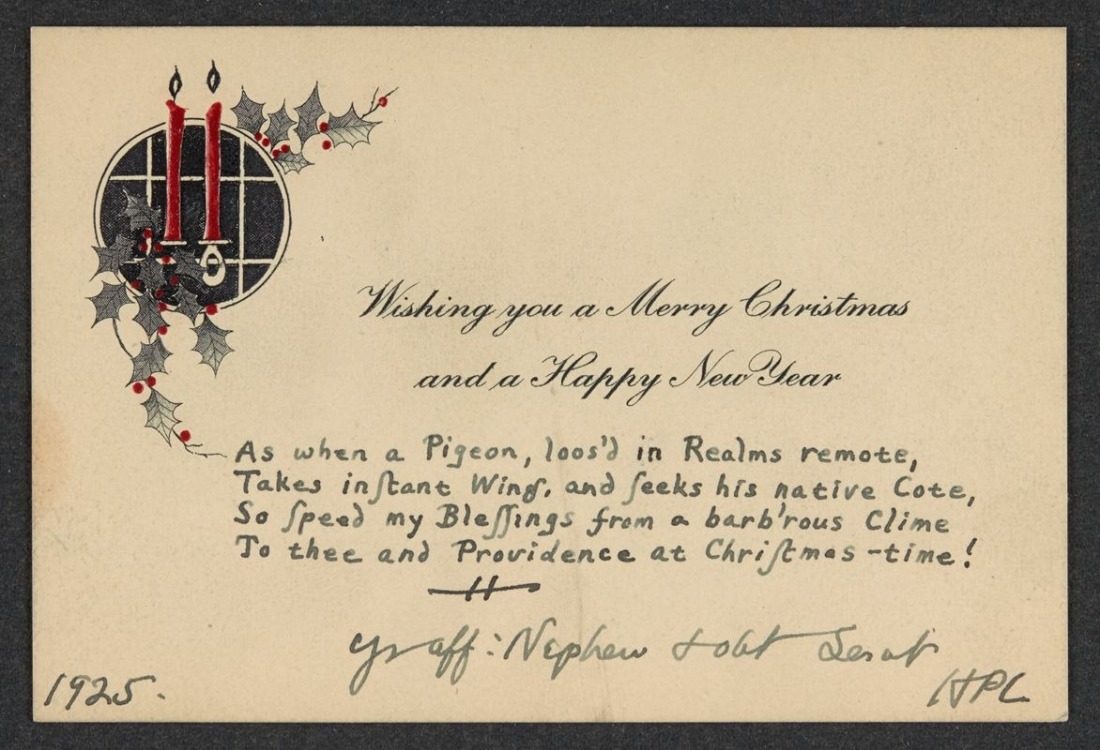

To Sarah Susan Lovecraft

May these dull verses for thy Christmastide

An added ray of cheerfulness provide,

For tho’ in art they take an humble place,

Their message is not measur’d by their grace.

As on this day of cold the turning sun

Hath in the sky his northward course begun,

So may this season’s trials hold for thee

The latent fount of bright futurity!

Yr aff. son & obt Servt., H.P. L., The Ancient Track 311

One Christmas poem to Lovecraft’s mother survives, though there are other examples of poetry he wrote to her on other occasions. These were likely some of his earliest Christmas Greetings, written during childhood and early adulthood, until his mother’s passing in 1921.

To Verna McGeoch

Tho’ late I vow’d no more to rhyme,

The Yuletide season wakes my quill;

So to a fairer, flowing clime

An ice-bound scribbler sends good will.

The Ancient Track 314

Two poems survive to Verna McGeoch, who was Official Editor of the United Amateur Press Association during Lovecraft’s term as president (1917-1918). The 1920 census shows McGeoch lived in St. Petersburg, Florida (“a fairer, flowing clime”), while Lovecraft froze in Providence. We know this poem was sent before 1921, because in the autumn of that year, Verna married James Chauncey Murch of Pennsylvania, and thus became Mrs. Murch and moved to that state.

To S. Lillian McMullen

To poetry’s home the bard would fain convey

The brightest wishes of a festal day;

Yet fears they’ll seem, so lowly is the giver,

Coals to Newcastle; water to the river!

The Ancient Track 318

One poem to Susan Lillian McMullen survives; she also published poetry under the pseudonym Lillian Middleton. A prominent poet in amateur journalism, Lovecraft wrote an essay praising her work, “The Poetry of Lillian McMullen” (CE 2.51-56), which would not be published during his lifetime. The two met at a gathering of amateurs in 1921. Their relations appear to have been cordial, though tempered by some of his criticisms of her poetry, and their correspondence was likely slight.

To Edith Miniter

From distant churchyards hear a Yuletide groan

As ghoulish Goodguile heaves his heaps of bone;

Each ancient slab the festive holly wears,

And all the worms disclaim their earthly cares:

Mayst thou, ‘neight sprightlier skies, no less rejoice,

And hail the season with exulting voice!

The Ancient Track 320

Five Christmas poems survive from Lovecraft to Edith Miniter, the grand dame of Boston’s amateur journalists. Miniter, among all of Lovecraft’s correspondents and fellow amateurs, was able and willing to take the piss a little with him, and wrote the first Lovecraftian parody, “Falco Ossifracus” (1921)—hence Lovecraft’s adoption of her nickname “Goodguile” for him.

To Anne Tillery Renshaw

Madam, accept a halting lay

That fain would cheer thy Christmas Day;

But fancy not the bard’s good will

Is as uncertain as his quill!

From the Copy-Reviser, The Ancient Track 311

Two poems survive to Anne Tillery Renshaw, teacher, editor, and amateur journalist. Lovecraft’s sign-off as “the Copy-Reviser” suggests their positions in amateur journalism at that time; Lovecraft had a tendency to correct metrical irregularities in poems of amateur journals he edited, and sometimes worked to revise the poetry of others. A Christmas card from Renshaw to Lovecraft survives.

To Laurie A. Sawyer

As Christmas snows (as yet a poet’s trope)

Call back one’s bygone days of youth and hope,

Four metrick lines I send—they’re quite enough—

Tho’ once I fancy’d I could write the stuff!

The Ancient Track 316

A single poem survives to amateur journalist Laurie A. Sawyer, whom Lovecraft described as “Amateurdom’s premier humourist” (CE 1.258). Sawyer was also president of the Interstate Amateur Press Association in 1909, and a leading figure of the Hub Club in Boston, moving in the same circles as Edith Miniter. She is known to have met Lovecraft at amateur conventions in Boston, and she helped issue the Edith Miniter memorial issue of The Tryout (Sep 1934).

To L. Evelyn Schump

May Yuletide bless the town of snow

Where Mormons lead their tangled lives;

And may the light of promise glow

On each grave cit and all his wives.

The Ancient Track 316

A single poem survives to amateur journalist and poet L. Evelyn Schump. She graduated from Ohio State University in 1915 and apparently took up the teaching profession in Ohio. The Church of Latter-Day Saints was established in Kirkland, Ohio during the 1830s until major schisms rent the church, whose members moved on to Missouri. Presumably there is some correspondence, now lost, behind this reference. Given how lightly Lovecraft touches on the issue of polygamy (officially rescinded in 1904), it isn’t likely she was a member of the congregation. As an amateur journalist, Lovecraft called her “a light essayist of unusual power and grace” (CE 1.224),

There are undoubtedly many Christmas Greetings that have been lost over the years, and what remains is little more than a sample of the whole. Yet it is clear that Lovecraft put his time and effort into crafting these verses, no matter how slight or silly, and even if he could afford no more than a card and a stamp, perhaps they spread a little cheer on long winter nights.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein uses Amazon Associate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.