Os Mitos de Lovecraft (2020) is a crowdfunded Brazilian black-and-white graphic anthology edited by Douglas P. Freitas and published by Skript, probably best known for the deluxe hardcover edition which has a cover modeled on the bound-in-human-skin Necronomicon ex Mortis from Evil Dead 2 and Army of Darkness. Like its fellow Brazilian Lovecraftian anthology O despertar de Cthulhu em Quadrinhos (2016), while there is a common theme in terms of subject, the style and tone of the individual works inside varies considerably. Every style of comic art and horror can be represented under the broad remit of Lovecraftian comics, from straight adaptations of Lovecraft in exquisite realistic depiction to splatterpunk-esque gore fests with plenty of airbrush-style gore streaks to lighter works with more cartoonish tentacled Cthulhu-esque characters.

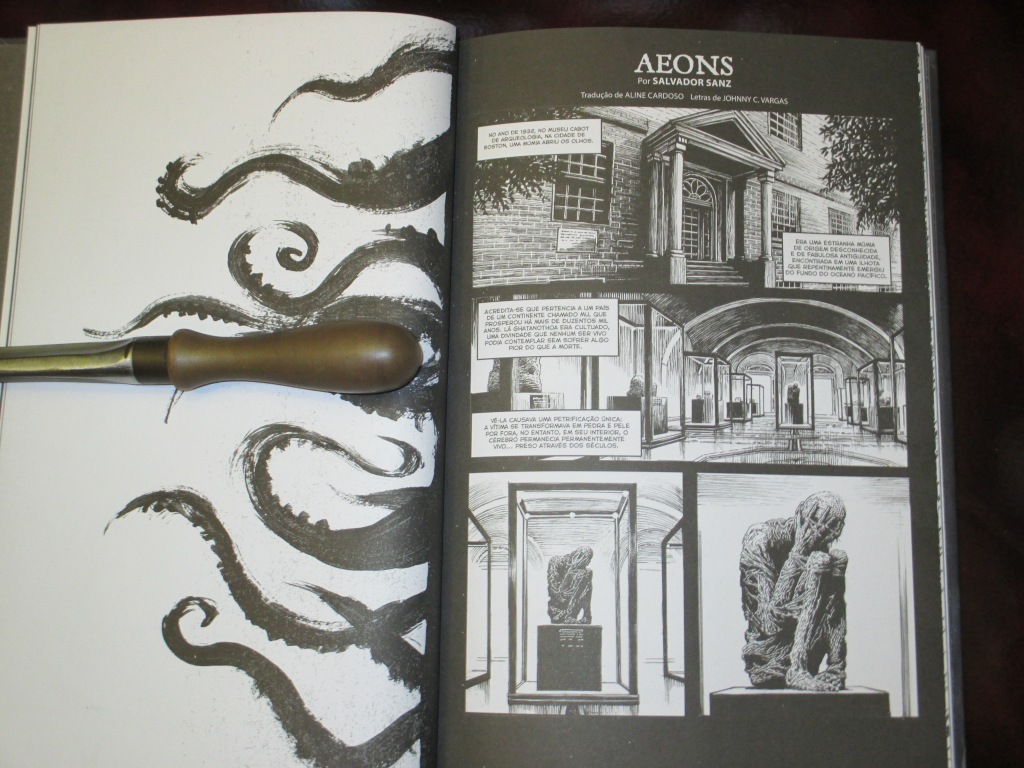

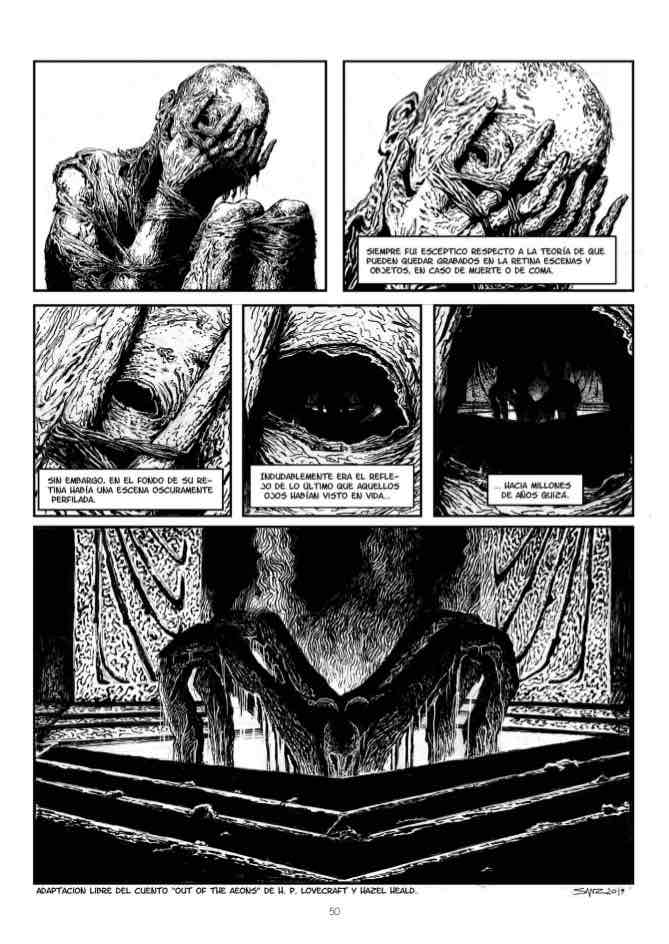

The anthology begins with an absolute masterpiece in two pages, by Argintenean artist Salvador Sanz, which originally appeared in the Spanish-language graphic horror anthology Cthulhu 23; for this anthology, it was translated into Brazilian Portuguese by Aline Cardoso and re-lettered by Johnny C. Vargas. This is a distillation of “Out of the Æons” (1935) by Hazel Heald & H. P. Lovecraft, subtracting all the human characters, the drama, and the fantastic history deciphered from the scroll in exchange for focusing on a masterful rendering of the mummy who caught a glimpse of Ghatanothoa—and paid the price.

In a cinematic journey, the reader is taken closer and closer to the ancient petrified horror. The panels zoom in on the one eye that peeks out between gnarled fingers. To the dark image that is still captured there, on the retina. The detail on the art, the pacing, and the execution of the concept, which boils down the essence of the Lovecraft/Heald horror story into two pages, is exquisite.

※

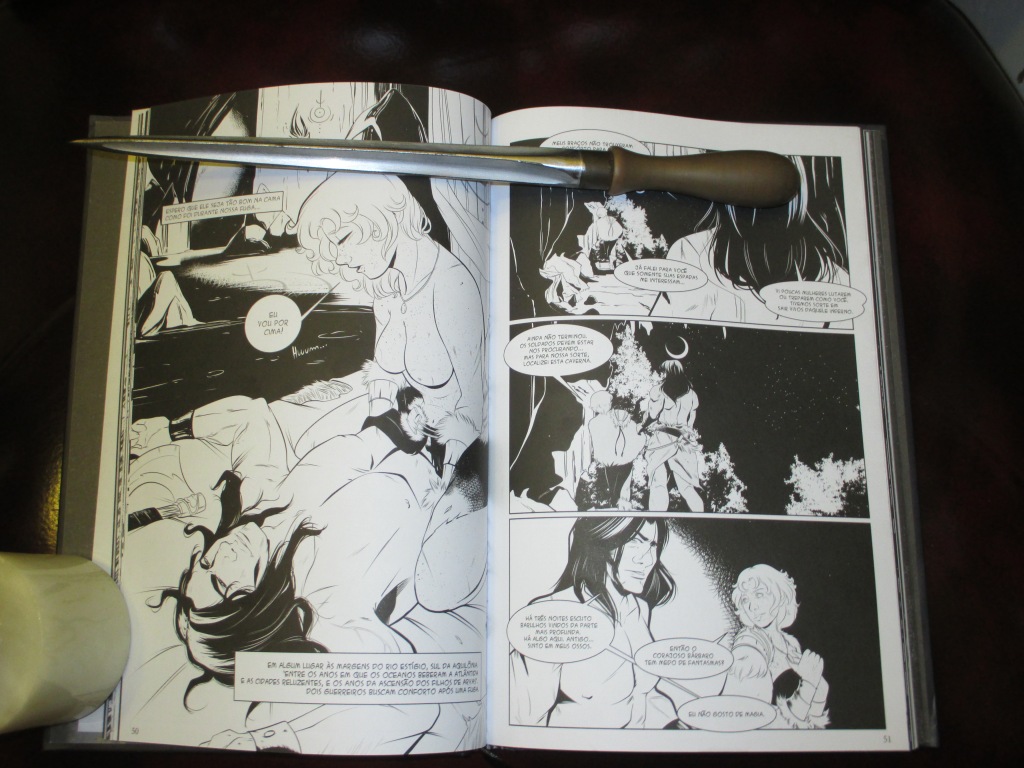

Freitas’ own contribution to Os Mitos de Lovecraft is “Sob As Trevas” (“Beneath the Darkness”), in collaboration with illustrator and comic creator Chairim Arrais. This is a tongue-in-cheek 8-page sword & sorcery story involving a nameless Cimmerian warrior and their female partner Ruivas (“Red”/”Red-hair”). Freitas & Arrais are clearly referencing Robert E. Howard’s most famous creation, Conan the Cimmerian, and aren’t coy about it:

| Em algum lugar às margens do rio Estígio, sul da Aquilônia, ‘entre os anos em que os oceanos beberam a Atlântida e as cidades reluzentes, e os anos da ascensão dos filhos de Aryas’. Dois guerreiros buscam conforto após uma fuga. | Somewhere on the banks of the River Styx, south of Aquilonia, ‘between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the sons of Aryas’. Two warriors seek comfort after an escape. |

| Os Mitos de Lovecraft page 51 | English Translation |

—Robert E. Howard, “The Phoenix on the Sword”

The character Ruivas is depicted similarly to the eponymous character in Arrais’ standalone comic “Red+18”; whether this is intended as an unofficial crossover, an Easter egg for fans of Arrais’ work, or just a coincidence—the character could as easily be a play on Red Sonja for the Marvel Comics, albeit sans the trademark mail bikini—is unclear, and maybe unimportant.

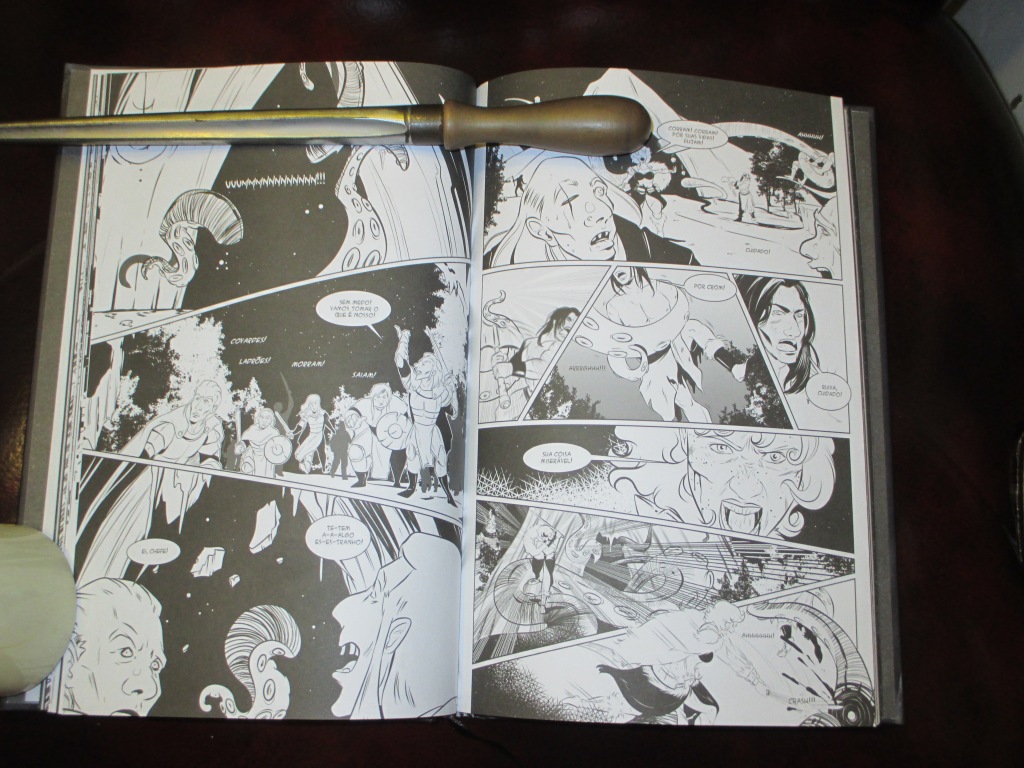

The story itself is fairly slight and straightforward: after successfully stealing a jewel, the pair of thieves hide out in a convenient cavern…which ends up being occupied by some nameless eldritch horror.

| Ei, Chefe! Te-tem a-a-a-algo es-es-tranho! | Hey, Boss! Th-there’s s-s-something s-strange! |

| Os Mitos de Lovecraft page 54 | English translation |

The story really wanted more pages; there’s little opportunity to really develop any atmosphere before the tentacles emerge from the darkness, and the action sequences are correspondingly cramped and staccato-like, crammed into increasingly more panels per page. With the in media res debut, the titillation, and the swift conclusion, this is strongly reminiscent of the kind of back-up feature that sometimes ran in Savage Sword of Conan, more of a sketch of an interlude than a full-fledged story.

Yet what there is there is fun. The writing is light-hearted, the chemistry between legally-not-Conan and Ruivas is alternately playful and rocky, and Arrais’ artwork does everything the script calls for. The brief sword & sorcery interlude sets a different tone than the other stories in the anthology, featuring more sex and action than horror or outright comedy. While I would have liked for it to delve more into the Howardian vibe of horror that permeated tales like “Xuthal of the Dusk” or “Red Nails,” limitations of space have to be acknowledged. Still, it would be nice if Freitas & Arrais had the opportunity to revisit the idea at a longer length more suitable to develop the characters and story at some point.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein uses Amazon Associate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.