| Erik Kriek hat etwas sehr Heikles gewagt: in Zeichnungen einzugangen, was man am besten und effektivsten der Phantasie des Lesers überlässt. Jeder, der ein Erzählung von H. P. Lovecraft, dem Meister der amerikanischen Ostküsten-Horrorgeschichten, liest, macht sich eigene Vorstellungen von den Monstern. Ich lasals kleiner Jungemeine erste Lovecraft-Geschichte, als mein Vater mir eine dicke Anthologie mit englischen und amerikanischen Horrorgeschichten schenkte: Vor und nach Mitternacht. Die sparsamen Illustrationen stammten von Eppo Doeve, unde heute, sechzig Jahre später, steht dieses Buch immer noch in meinem Regal, sind die Erzählungen in meinem Gedächtnis, befinden sich die Bilder auf meiner Netzhaut. Merkwürdige Zeichnungen, unvollständig, sparsam und, so wie es sich gehört, in Schwarzweiẞ. Das BUch hat eine lebenslange Faszination ausgelöst: Immer noch kaufe ich regelmässig Horror. Es erscheint keine Neuausgabe von Ambrose Bierce oder Roald Dahl, in die ich nicht hineinschaue, um ze sehen, ob darin – wie kurz auch immer – nicht doch etwas Neues steht. | Erik Kriek has dared to do something very tricky: to capture in drawings what is best and most effectively left to the reader’s imagination. Everyone who reads a tale by H. P. Lovecraft, the master of American East Coast horror stories, creates Monsters from his own Imagination. I read my first Lovecraft story as a young boy when my father gave me a thick anthology of English and American horror stories: Before and After Midnight. The sparse illustrations were by Eppo Doeve, and today, sixty years later, this book is still on my shelf, the stories are in my memory, the images are on my retina. Strange drawings, incomplete, sparse and, as it should be, in black and white. The book triggered a lifelong fascination: I still buy horror regularly. No new edition of Ambrose Bierce or Roald Dahl appears that I don’t look into to see if there isn’t something new in it – however briefly. |

| Forward by Gerard Soeteman | English translation |

Vom Jenseits und andere Erzählungen (“From Beyond and other Tales,” 2013, Avant-Verlag) is a German-language collection of graphic adaptations of Lovecraft’s stories “The Outsider,” “The Color Out of Space,” “Dagon,” “From Beyond,” and “The Shadow over Innsmouth.” The adaptations are very faithful to the original, often down to the level of the language, which is often directly quoting from the German-language translation of Lovecraft’s stories.

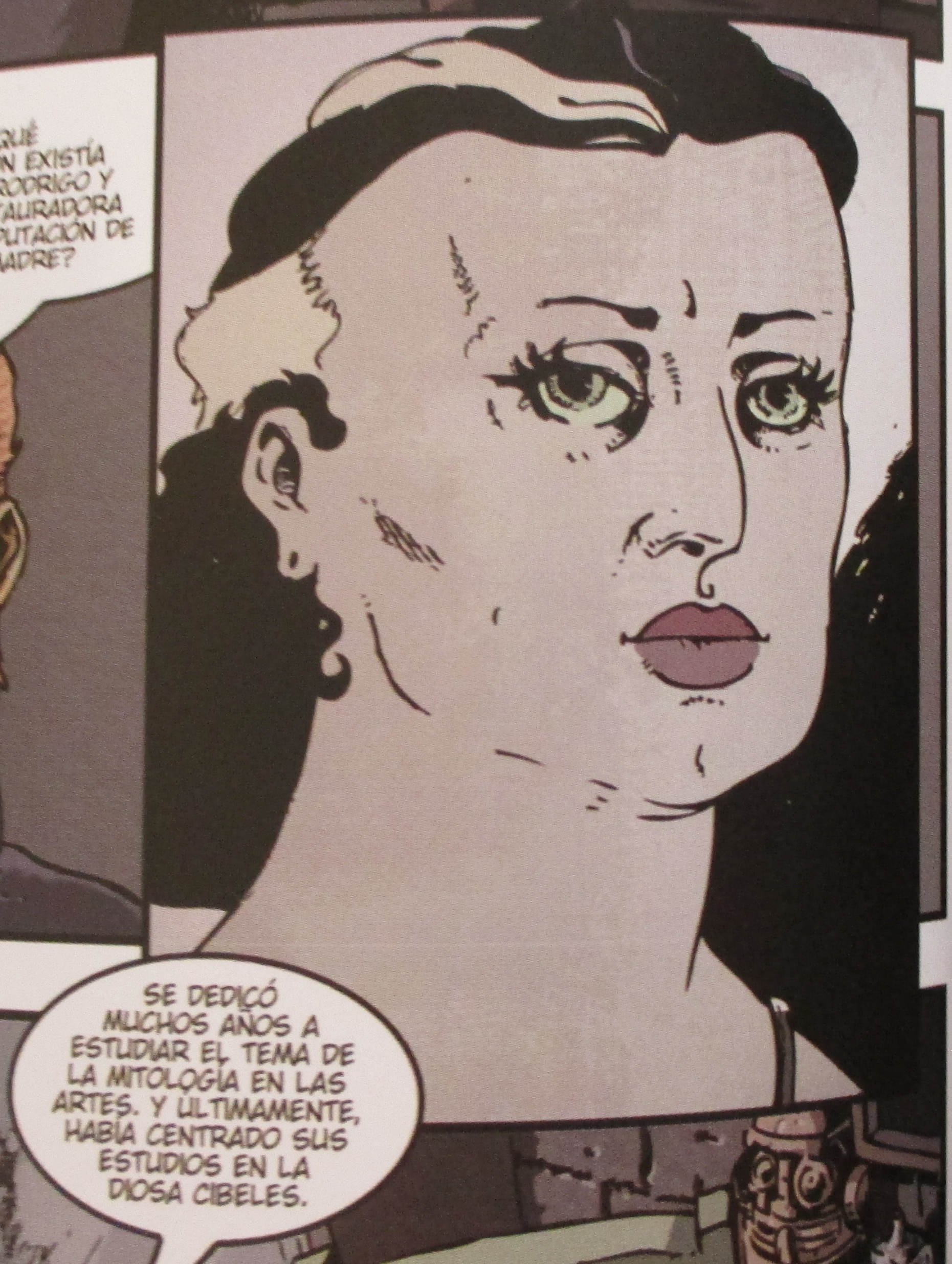

Kriek, who is both writer and artist, has lavished most of his creativity on the art itself—with great care and attention to the setting and costumes of the characters, putting them in period-appropriate dress and rooms, giving them little quirks Lovecraft didn’t mention but might well have imagined. The style makes heavy use of shadows for the panes of the face and the set of the body, very reminiscent of the black-and-white artwork of 1970s Warren horror magazines like Creepy or Eerie, but cleaner and starker. The clear-cut reality of the normal frames gives Kriek’s wilder, more imaginative and fantastic pages more impact.

There have been so many graphic adaptations of Lovecraft’s fiction over the years by so many artists, it is difficult to find points for fair comparison—or perhaps it is better to say, it’s hard to know where to start.

“The Outsider,” for example, is a 2,595 word short story; Kriek adapted it in six pages. Alec Preston Stevens also adapted “The Outsider” in six pages in Prime Cuts #1 (1987), so too did Bhob Stewart and Steve Harper in Monsters Attack #2 (1989), and Devon Devereaux and Tom Pomplun in Graphic Classics: H. P. Lovecraft (2002); Hernán Rodríguez did it in 14 pages (as “The Stranger”) in Heavy Metal (vol. 32, no. 8, Fall 2008), Tanabe Gou stretched it out to 24 pages for his 2007 collection …and because they are all adaptations of the same story, a really deep analysis could almost go line-by-line and panel-by-panel in comparison.

The same could be said for most of Lovecraft’s other stories. He did not leave a particularly large body of work, but nearly every story and many of the poems he wrote or had a hand in have been adapted in some fashion at some point by somebody—even relatively obscure works like the revision “Medusa’s Coil” is represented by “Medusa’s Curse” (1995) by Sakura Mizuki (桜 水樹氏) and “Nelle Spire di Medusa” (2019) by Massimo Rosi & Tommaso Campanini. Probably only Edgar Allan Poe has received better coverage in the comics.

Which might beg the question: why? What does a new graphic adaptation of Lovecraft bring to the audience that wasn’t there before? Was there something lacking about all the previous adaptations of “The Outsider” that moved Kriek to try his hand at Lovecraft in his own vivid style? Kriek’s adaptation in particular is very faithful to the original; he was not adapting the stories to his own times, not injecting any contemporary value or message into Lovecraft’s narrative. These adaptations are a genuine effort to do justice Lovecraft’s original vision, while also showcasing Kriek’s own interpretation.

Which might be the answer in itself. Comic adaptations of Lovecraft exist because the stories are there in the public domain. No one can stop you. They are mountains to be climbed, caves to be spelunked. The fact that you are not the first to climb to the top of a particular mountain does not take away from the achievement of doing it. Anyone who completes a comic adaptation of “From Beyond” or “The Color Out of Space” may be competing, in some philosophical fashion, with every other artist who seeks to express the inexpressible in some fixed medium, but there is never going to be any final winner. Someone else is bound to come along and try their hand at it…but people can point to books like Vom Jenseits und andere Erzählungen and say: “Already, here’s what I did. What have you got?”

Kriek’s collection ends with “Vom Jenseits” (“From Beyond”) by Milan Hulsing, which is not the short story of the same name but a short biography of H. P. Lovecraft illustrated with a few choice pictures based on photographs of Lovecraft and his life. “Jenseits” is the German term for “on the other side” or “beyond,” but it can also refer to the afterlife, the underworld, the next world—in other words, there are some connotations that may or may not quite line up exactly with the English terms. Euphemistically, we are doing the same thing; catching a glimpse of another world…only the resonator is the book in our hands.

Addendum: I could not end this review without including this anecdote from the introduction:

| Lovecrafts Erzählung Das Ding auf der Schwelle faszinierte und fasziniert mich noch immer so, dass ich sie, als eine Hollywood-Produzentin mich bat, einen Polit-Thriller zu schreiben, zu einem Drehbuch umgerbeitet habe. Um die geforderte Aktualität hineinzubekommen, dachte ich mir einen sehr wichtigen Berater eines neugewählten amerikanischen Präsidenten aus, der in einer kleinen neuenglischen Stadt à la Lovecraft landet. Man erlebt, wie er durch Seelenwanderung allmählich verrückt wird und zu glauben beginnt, dass das Ende der Welt, wenn es nicht sowieso schon bevorsteht, von ihm herbeigeführt werden muss. Als vollkommen Wahnsinniger reist er zerück nach Washington, um dort als Mitglied des Nationalen Sicherheitsrats dem Präsidenten verhängnisvolle Ratschläge zu geben … Die Produzentin lehnte das Drehbuch ab: „Wahnsinnige würden in Washington niemals in solche Positionen gelangen.“ Und dann … kam Oliver North, um Reagan zu dienen, und – später – taten Bushs Ratgeber ihre segensreich Arbeit so, dass die Vereinigten Staaten in maẞlose Schulden gestürzt wurden, um heillose Kriege zu führen und zu bezahlen … tja. | Lovecraft’s tale “The Thing on the Doorstep” fascinated and still fascinates me so much that when a Hollywood producer asked me to write a political thriller, I reworked it into a screenplay. To get the required topicality in, I thought up a very important advisor to a newly elected American president who ends up in a small New England town à la Lovecraft. You see him gradually go insane through transmigration of souls and begin to believe that the end of the world, if it isn’t imminent anyway, must be brought about by him. As a complete madman, he travels back to Washington to give disastrous advice to the president as a member of the National Security Council … The producer rejected the script: “Insane people would never get into such positions in Washington.” And then … Oliver North came to serve Reagan, and – later – Bush’s advisors did their beneficent work in such a way that the United States was plunged into gross debt to wage and pay for hopeless wars … oh well. |

| Forward by Gerard Soeteman | English translation |

English-language readers in the United States have a bad habit of not paying attention to what happens outside the Anglosphere, but the non-English-speaking world is large, and they pay attention to what we do here…because it affects them too. The resonator lets those from beyond see us as well as we see them; it translates both ways…and the world of H. P. Lovecraft is so much bigger and weirder than we can imagine.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein uses Amazon Associate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.