| Sonia (Assise en train d’écrire, elle s’interrompt, levant la tête et s’exprimant a voix haute): Howard est mort. Quelle tristesse! Et moi, qui ne suis plus tout à fait sa veuve… Divorcée, remariée, je ne peux plus être sa veuve officielle. | Sonia (Sitting down to write, she interrupts herself, raises her head and speaks out loud): Howard is dead. What sadness! And I, who am not quite his widow anymore… Divorced, remarried, I can no longer be his widow, officially. |

| Howard, Mon Amour 19 | English translation |

Ever since the publication of The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft (1985) by Sonia H. Davis in various recensions, there has been great interest in the marriage of H. P. Lovecraft, and in his wife Sonia Haft Greene, who remarried in 1936 and became Sonia H. Davis. As the story of their marriage has unfolded in letters and memoirs, the narrative possibilities have struck several writers. Richard Lupoff included Sonia as a character in Lovecraft’s Book (1985), later expanded or restored as Marblehead (2015), to give one prominent example. Readers and scholars who have traced the story of their meeting, their work on the Rainbow, their collaborations “The Horror at Martin’s Beach” (1923), “Four O’Clock” (1949), Alcestis: A Play (1985), and “European Glimpses” (1988), and their final separation all speak to a dramatic narrative—some might say a tragedy, for all human lives tend toward tragedy at the end.

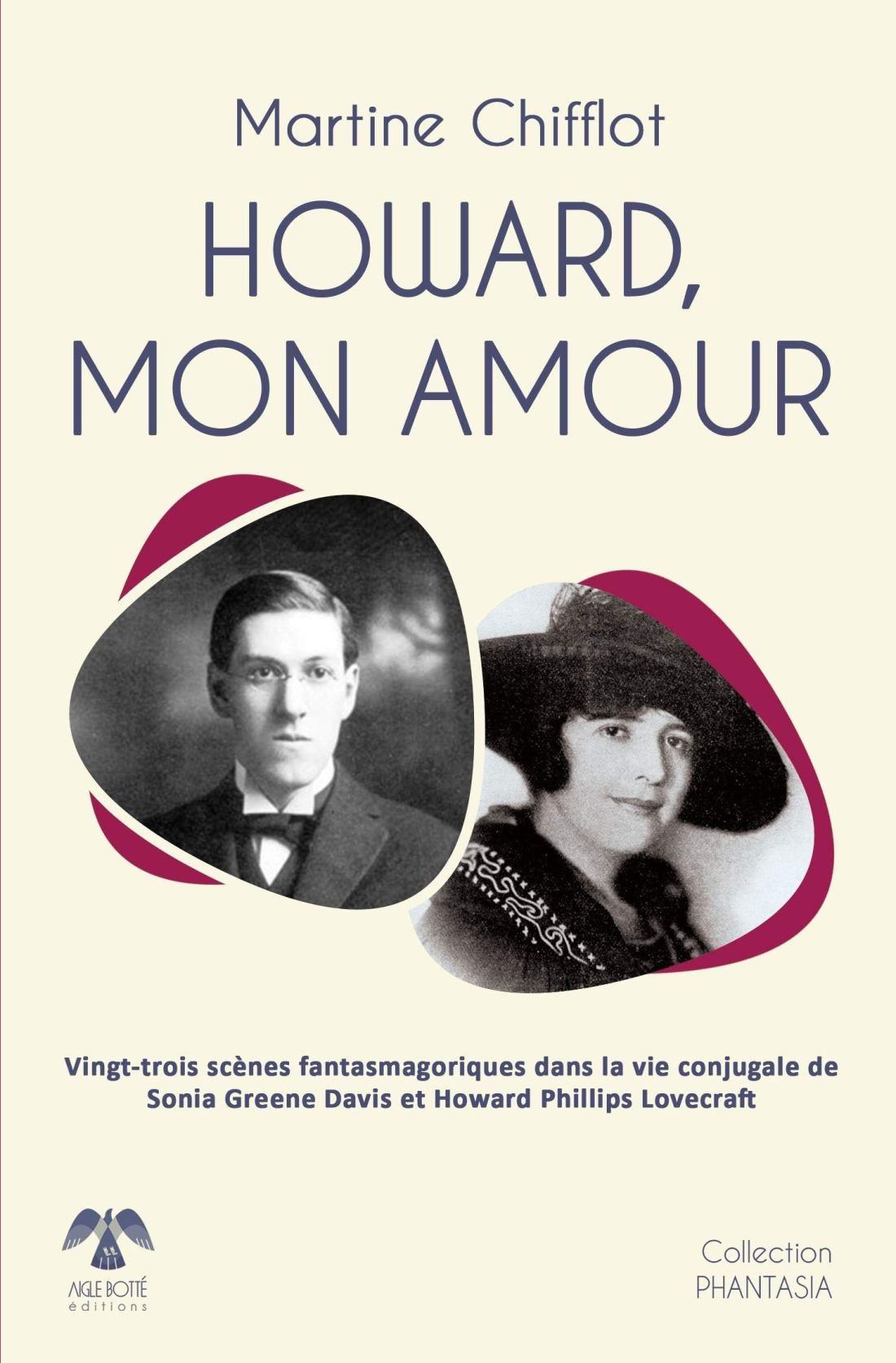

Howard, Mon Amour is a short drama in 23 scenes by Martine Chifflot. The scene is 1946; their mutual friend Wheeler Dryden has informed Sonia of the death of H. P. Lovecraft, nearly a decade prior. The two had fallen out of touch, and apparently contact had been broken prior to her third and final marriage to Nathaniel A. Davis. Alone while writing, the phantom of Lovecraft appears…whether his ghost, or a hallucination born of her grief, never quite clear. It doesn’t really matter.

| Howard: Je suis ici, Sonia; je resterai aussi longtemps que tu vivras. Les choses là-bas ne sont pas tout à fait semblables à ce que l’on raconte, à ce que, moi-même, j’en ai dit et je ne suis pas autorisé à en parler mais il a été permis que je revienne… pour toi, comme pour t’accompagner, comme pour te remercier. | Howard: I am here, Sonia; I will stay as long as you live. Things down there are not quite the same as we are told, as I myself have said, and I am not allowed to talk about them, but I have been allowed to come back… for you, as if to accompany you, as if to thank you. |

| Howard, Mon Amour 22 | English translation |

The French found an early appreciation for Lovecraft, and not just his fiction but many of his letters and associated biographical materials have been translated into French, including Sonia’s memoir. “Un mari nommé H.P.L.” (“A Husband Named H.P.L.” in Lovecraft (Robert Laffront, 1991) appears to have been Chifflot’s main source of data on the marriage, and Chifflot’s drama is fairly accurate to the facts. She may put words into her character’s mouths, but the events play out largely in accordance with Sonia’s account of the marriage, warts and all; the drama of the scenes is a little heightened in the telling, the events more emotional and detailed, but also emotionally true to how Sonia told them herself.

| Tante Lilian (ou Sonia L’imitant), apres un moment de silence): Chère Sonia, nous vous remercions mais cela est tout bonnement impossible. Voyez-vous, Howard et nous-mêmes sommes des Phillips et nous ne pouvons envisager que l’épouse de Howard doive traviller pour vivre à Providence. Cela constitue une sort de déshonneur que nouse ne pouvons tolérer pour Howard et pour nous-mêmes. Non. L’épouse de Howard Phillips Lovecraft no peut entretenir son ménage, ni ses tantes. C’est le devoir du mari de subvenir aux besoins familiaux et Howard a joué de malchance à cet égard. Nous connaissons, tout comme vous, les grandes qualités de Howard et nouse aimerions vous voir réunis mais cela ne se peut dans de telles conditions. Vous nous entretiendriez et nous seriouns à votre charge. Ce serait une honte pour nous malgré votre générosité. Cela ne se peut, chère Madame… et nous devrons tous souffrir en silence. | Aunt Lilian (or Sonia imitating her), after a moment of silence): Dear Sonia, we thank you but this is simply impossible. You see, we and Howard are Phillips and we cannot contemplate Howard’s wife having to work to live in Providence. This is a dishonor that we cannot tolerate for Howard and ourselves. No. The wife of Howard Phillips Lovecraft cannot support his household, nor his aunts. It is the husband’s duty to provide for his family, and Howard has been unfortunate in this regard. We know, as you do, the great qualities of Howard and we would like to see you reunited, but it is not possible under these conditions. You would be supporting us and we would be in your charge. It would be a shame for us despite your generosity. It cannot be, dear Madame… and we must all suffer in silence. |

| Howard, Mon Amour 64 | English translation |

Most of the scenes are monologues, recalling some incident from their married lives; the more interesting scenes are dialogues, where Howard and Sonia actually have a bit of back-and-forth; other characters like Howard’s aunts Lillian and Annie have brief roles, and as suggested, could simply be retold by the actress playing Sonia doing their parts. It is a work meant to be not just read, but acted out; Chifflot herself has performed on stage in the role of Sonia:

For all the research that went in Howard, Mon Amour, there are a few idiosyncrasies that go beyond the facts. Little attention is given to Sonia’s Jewish identity or how Howard’s prejudices and antisemitism spiked during his stressful stay in New York, for example. There is an odd moment where Sonia believes that Howard’s correspondence with his revision client Zealia Bishop caused a “cooling” (refroidissement) of their relationship; and another where Sonia is said to dislike Crowley (in reality, Sonia and Aleister Crowley never met, it’s all an internet hoax). Which can all be explained as dramatic license rather than error or intentional misdirection. These are things that might stand out to a Lovecraft scholar with a penchant for pedantry more than a Lovecraft fan.

The emotional core of the work is true, however. In many ways, Sonia did find herself haunted by Lovecraft’s ghost for the rest of her life; his legacy clung to her as people asked her about the marriage, and many of her surviving letters survive because they are about Howard or addressed to his friends like August Derleth and Samuel Loveman. In Howard, Mon Amour, Sonia seems to accept that…and that she still loves him. Which, perhaps, is true. It was never love that got in the way of their relationship, but everything else around them: her health, his aunts, their finances, a difference in wants and needs, what they were and were not willing to do.

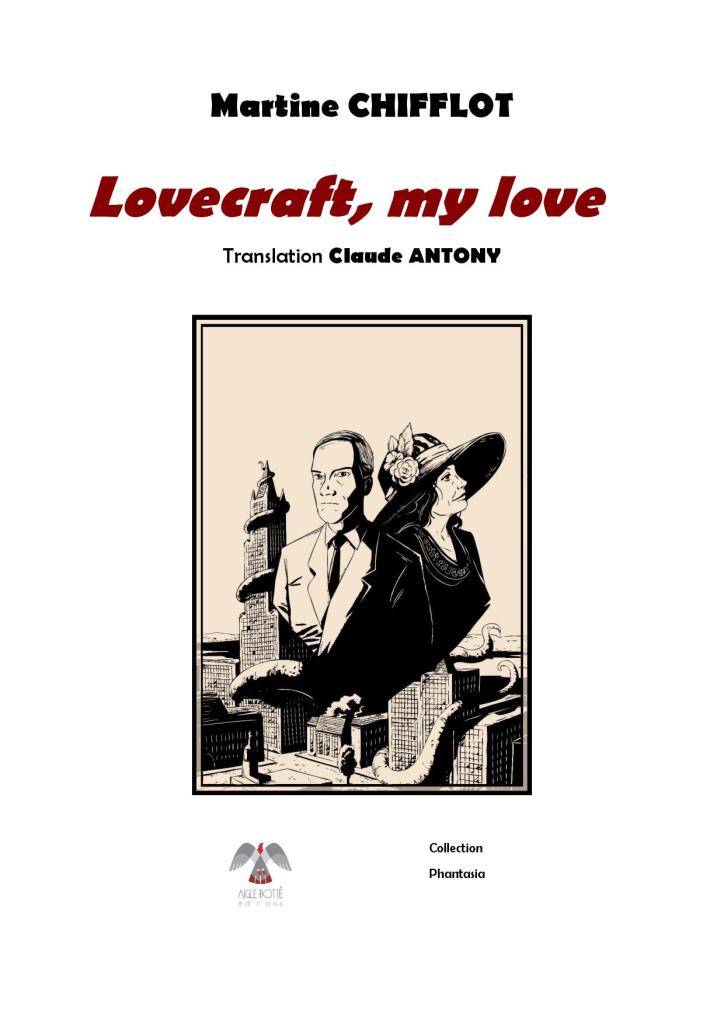

Howard, Mon Amour by Martine Chifflot was published in 2018 by L’Aigle Botté, and has been performed on stage as “Lovecraft, Mon Amour.” An English translation by Claude Antony has been announced:

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard & Others (2019) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014).