I first met him at the Boston Convention when the amateur journalists gathered there for this conclave, in 1921. I admired his personality but frankly, at first, not his person.

As he was always trying to find recruits for amateur journalism he offered to send me some amateur literature not only form his own pen but also from the pens of others whose effort he felt was worthy of my perusal; works that appeared in the different amateur journals.

From then on we kept up quite a steady correspondence, and I felt highly flattered when he told me in some of his letters that mine indicated a freshness not born of immaturity, but rather a refreshingness because of originality and the courage of my convictions when I disagreed.

And I disagreed often, not just to be disagreeable, but because I wanted, if possible, to eradicate or partly remove some of his intensely fixed ideas.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 132

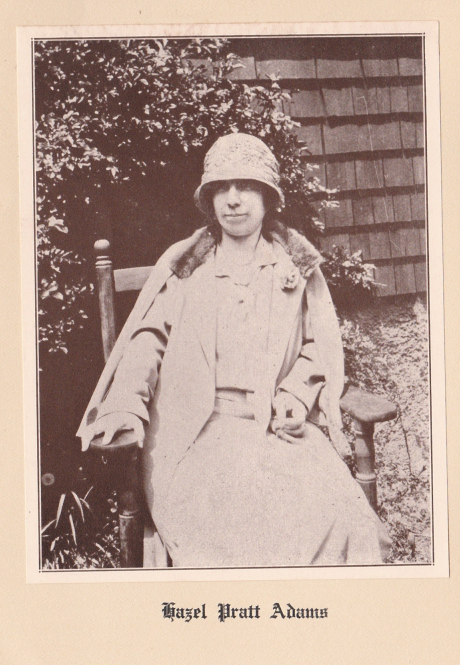

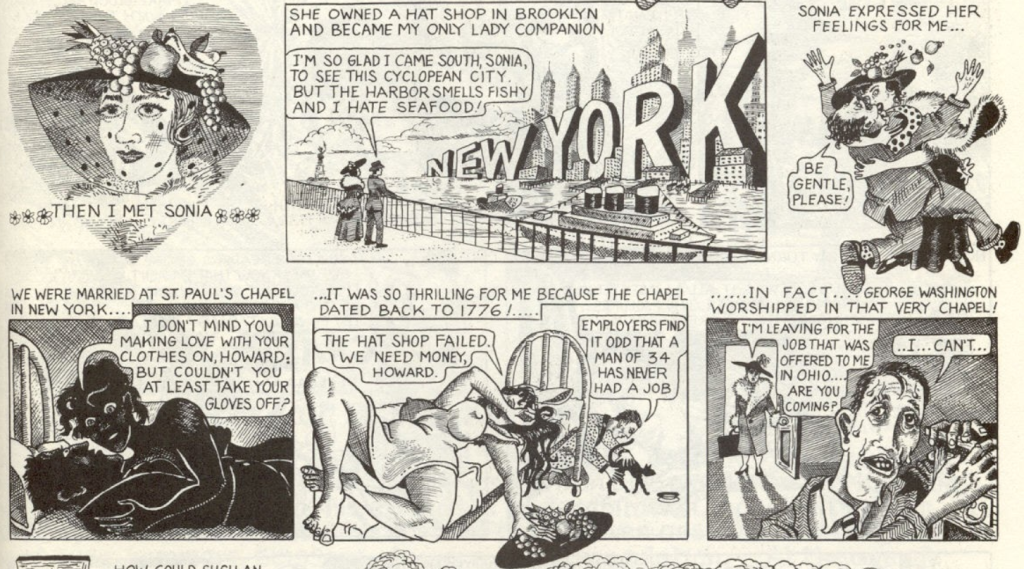

Sonia Haft Shafirkin was born to a Jewish family in 1883, in or near Ichnya, in the present-day Ukraine; then the Russian Empire. By the time Sonia was 7 years old, her father had left or deserted the family, and her mother obtained a divorce and emigrated westward. Sonia spent two years in the United Kingdom at school; her mother traveled on to the United States of America, remarried, and sent for her daughter. The homelife was not entirely happy, and her step-father soon put his new stepdaughter to work; Sonia was apprenticed to a milliner at age 13. At age 16, she married a 25-year-old Russian immigrant, Samuel Greene (ne Seckendorff). Her first child, a son, was born the next year and died in infancy. A daughter, Florence Carol Greene, was born in 1903.

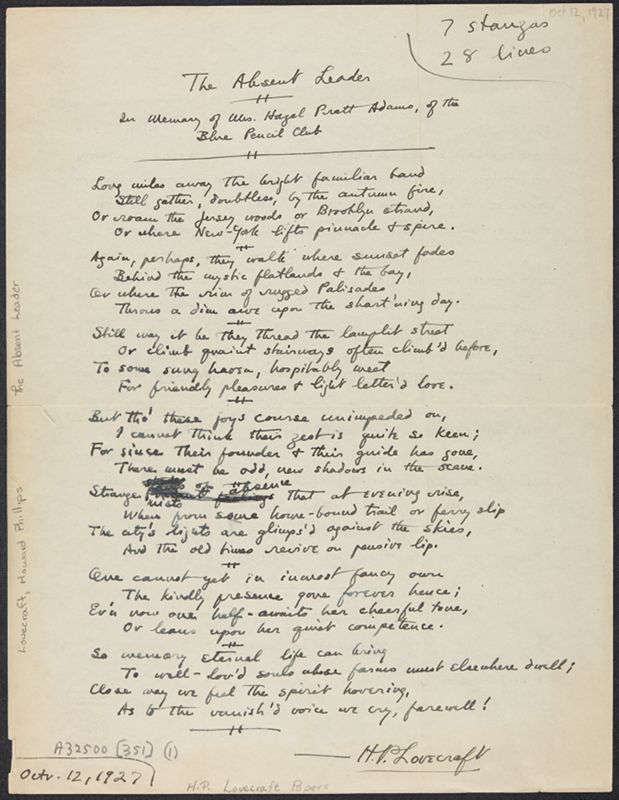

The marriage did not last; Samuel Greene died in 1916. Sonia Haft Greene lived in New York continued to climb the ranks of the millinery trade, attended night schools and evening courses, raised her daughter, and helped to care for her mother (now separated from her husband) and two half-siblings. Sonia was draw into societies like the socially progressive Sunrise Club and the Blue Pencil Club, an amateur journalist affiliate where she met James F. Morton. Because of her connections with the BPC, Sonia attended the July 1921 amateur journalists convention in Boston, Massachusetts…and there, met H. P. Lovecraft.

It was not love at first sight, but there was a connection made, and the two began to correspond. We cannot say exactly what Sonia saw in Lovecraft, but consider her circumstances: a widow or divorcee, a single mother of an almost-grown daughter, financially self-sufficient, with literary interests…and here was an intelligent man who no doubt wrote her extremely gentlemanly yet challenging letters, probably filling pages on topics literary and philosophical…and Sonia apparently answered back. While many memoirs speak of Sonia’s beauty, few of them discuss her intelligence and wit…but Lovecraft did.

Lovecraft persuaded her to join the United Amateur Press Association, the amateur journalism group he was associated with, and she generously subscribed $50 to the fund (the equivalent of a month’s rent in many New York apartments at the time). These first letters do not survive, but based on the remarks that appear in Lovecraft’s letters at the time, and Sonia’s own comments, we can get an idea of some of the contents. For example, when Lovecraft wrote:

Galba, yuh’d orta hear what she says about you in her latest 12-pager! […] I never before saw a nut quite like Mme. Greenevsky—it must be Slavonic blood For pure hot air she may have rivals, but the joke is that there is sound sense and profound literary erudition beneath all the nonsense. So she thinks Grandpa is egotistical? Hell! That’s what she told me at the convention—and then added that she never would have wasted her valuable time in trying to convert me if I were not an unusual specimen, or something like that. Her worst trouble is an absent sense of humour—the poor fish thought it was serious egotism when I told her that I despise all mankind and consider myself a cosmic intelligence aloof from the race. In letters Mme. G. is not at all egotistical—I was surprised at the Uriah-Heepness of her written as distinguished from oral arguments. But Holy Yahveh, what floral rhetoric! However, let me not libel an honest and learned thinker, who is really the most remarkable accession which amateurdom has had for some time.

—H. P. Lovecraft to the Gallomo, 31 Aug 1921, Letters to Alfred Galpin 104

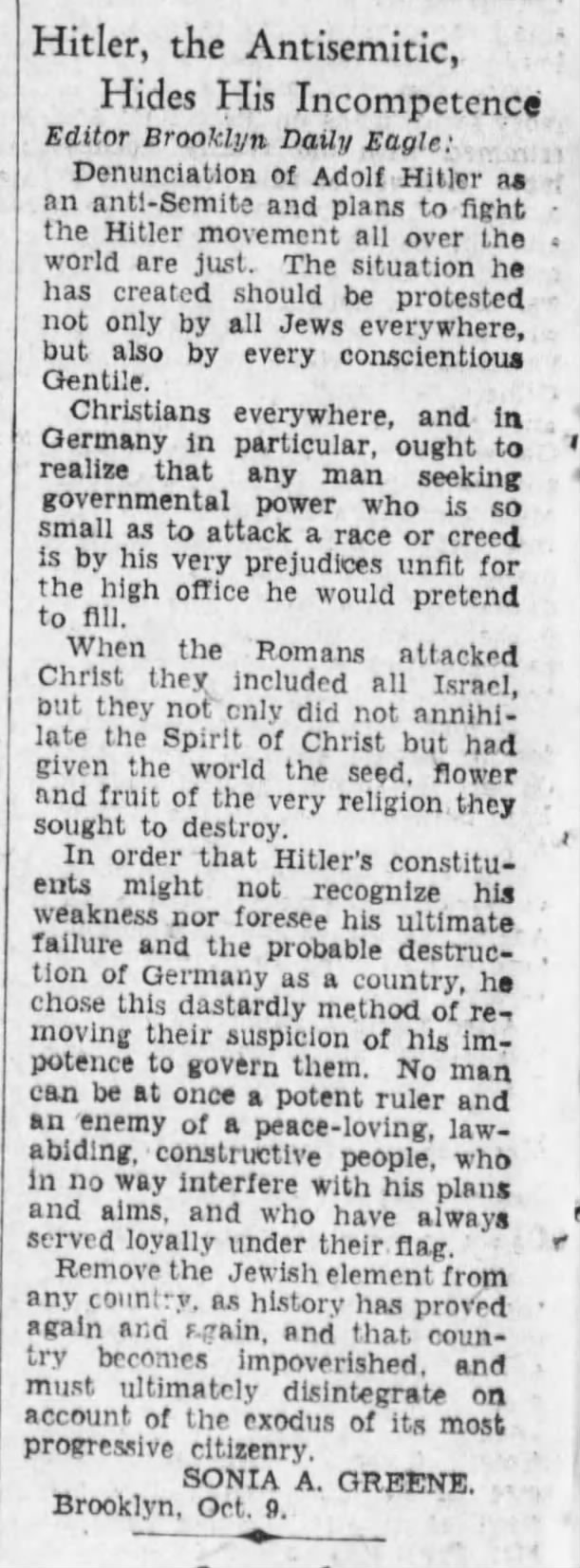

Alfred Galpin and Lovecraft had been reading and discussing Frederick Nietzsche (or related works like Schopenhauer’s Studies in Pessimism(1890), and Galpin’s essay “Nietzsche as a Practical Prophet”), and this had apparently spilled over into the letters with Sonia. At the same time that this July-August 1921 correspondence was taking place, Sonia and Lovecraft were planning out a new amateur journal, The Rainbow. The first issue (October 1921) contains a nominal essay by Lovecraft titled “Nietzscheism and Realism,” culled from excerpts from two of his letters to Sonia. It’s difficult to judge Sonia’s exact sentiments from Lovecraft’s letters, but some years later she wrote:

Editor Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

In last evening’s Eagle I was amazed to find that Dr. M.P. McDonald has so far misinterpreted Nietzsche’s philosophy as to state that one “should trample his neighbor down,” and that this is so typically exemplified in the subway, where we find even the most modest girls flailing their arms to get into a much crowded car. I fear Dr. McDonald is interpreting the German professor literally.

The proper interpretation to put upon his philosophy is that if Nietzsche had his way, there would never be such crowded subways and there would be no need for trampling of any kind.

It is appalling how many people read Nietzsche and how few know how to interpret him. Any one who really wishes to understand him should read H. L. Menken’s [sic] “The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche.” I would advise the biography by Frederic Halevy; after reading which, the reader will find Nietzsche as a practical prophet rather than a destructive one.

The average American girl or boy will answer, when asked about Nietzsche: “Oh, that’s the guy who is to blame for the war.” Upon further inquiry, “Have you read anything by Nietzsche?” you will hear: “Aw, no. I haven’t and I don’t want to! He’s no good to read about anyway!”

As with Caesar, the good is interred with Nietzsche’s bones, and all that appears evil in the eyes of the nonunderstanding majority is flagrantly and maliciously flaunted into the universe.

—Sonia Haft Greene to the Brooklyn Eagle, 10 Feb 1931

In her memoir, Sonia also wrote:

Yet, in one of his earliest letters to me, part of which I incorporated in my second issue of the Rainbow, he indicates the true reasons for being kindly, humane, just and merciful.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 145)

Nietzsche’s work is also notably antisemitic, which may have tied into another subject that they discussed in their letters: the poet Samuel Loveman, who had been re-introduced to amateur journalism through Lovecraft’s efforts.

Long before H. P. and I were married he said to me in a letter when speaking of Loveman, “Loveman is a poet and a literary genius. I have never met him in person, but his letters indicate him to be a man of great learning and cultural background. The only discrepancy I find in him is that his of the Semitic race, a Jew.”

Then I replied that I was a little surprised at H. P.’s discrimination in this instance—that I thought H. P.. to be above such a petty fallacy—that perhaps our own friendship might find itself on the rocks under the circumstances, since I too am of the Hebrew people […]

It was only after several such exchanges of letters that he put the “pianissimo” on his thoughts (perhaps) and curtailed his outbursts of discrimination. In fact, it was after this that our own correspondence became more frequent and more intimate until, as I then believed, H.P. became entirely rid of his prejudices in this direction, and that no more need have been said about them.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 147-148

Lovecraft apparently urged Sonia to write to Loveman as well. At first, Sonia demurred. However, she had occasion to visit Cleveland, where Loveman lived, and met him there. They got on quite well; Lovecraft heard of the trip through Sonia’s letters:

When I wrote to him later I deplored the fact that he, too, could not have been with us; that his presence would have made my happiness complete for that evening, etc.

In reply I found a letter from him at home which was quite warm and appreciative, coming from him, but even the warmth was bountifully intermixed with reservations.

By this time I had two correspondents: H. P. and S. L.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 133

In September 1921, Sonia stopped in Providence while traveling on business, meeting Lovecraft and his aunts and putting the finishing touches on the first issue of The Rainbow, which was published to some acclaim the next month. Their 1921 letters no doubt discussed the contents, and their letters from October 1921 to early 1922 must have discussed the contents of the second issue, which would be published in May 1922:

I am grateful to Mrs. Greene for her editorial in support of my literary policies, as indeed for many instances of a courtesy & generosity seldom found in this degenerate aera. You may be assur’d that I shall not diminish the frequency of the epistles I send her, tho’ I am of opinion that S. Loveman & my grandchild Alfredus deserve much of the credit for her retention in the United. I regret that she hath suffer’d indignites from Mrs. Houtain; whose cast of mind, I suspect, is not exempt from the petty cruelty & fondness for gossip which blemish the humours of the most commonplace females.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Rheinhart Kleiner, 25 Jan 1922, Letters to Rheinhart Kleiner & Others 194

However, Sonia also began to push another idea in her letters:

Her latest idea is to have a sort of convention of freaks & exotics in New York during the holidays; inviting for two weeks such provisional sages as Loveman, The Chee-ild [Frank Belknap Long, Jr.], & poor Grandpa Theobald [Lovecraft]! Only a sincere enthusiast could thus think of uprooting such outland fixtures from their native hearths!

—H. P. Lovecraft to Rheinhart Kleiner, 21 Sep 1921, Letters to Rheinhart Kleiner & Others 192

The idea of an amateur get-together in New York was a bit bold, but then Sonia had met both Lovecraft and Loveman separately, and must have known from their letters that Lovecraft had never met Loveman and desired to do so. It took some considerable convincing…but Sonia had considerable charm, and perhaps a secondary motive:

It was his prejudice against minorities, especially Jews, that prompted me to invite H. P. and S. L. to spend some time in New York, so that if H. P. never met a Jew before, I was happy to know that for the first time he would meet two of them, both of whom were favorably cultured and enlightened, and that the favored of the race is not limited to this infinitesimal number.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 148

Lovecraft had met Jewish people before, and Sonia’s hope of curing his prejudices didn’t work. However, he did accept her invitation to visit New York in April 1922 (if only to meet Loveman and visit with friends), and his letters to his aunts go into great detail about the attractions of the city and the graciousness of Sonia as a host. Then he departed for home, and their correspondence resumed.

The second (and last) issue of The Rainbow has a cover date of May 1922; this received a bit less attention than the first, and yet it must have been an expensive production. We’ll never know if it was the lack of reception, the cost, busyness on the part of Sonia and Lovecraft, or something else that caused her to cease publication. Yet their relationship continued after Lovecraft’s first New York adventure—and deepened.

Sonia made occasional visits to Providence, and on a trip to Magnolia, Massachusetts in June 1922, she invited Lovecraft to come along. The visit lasted from 26 June-5 July and resulted in the composition of at least two stories: “The Horror at Martin’s Beach” and “Four O’Clock”, with a third tale apparently unpublished.

The trip also saw the start of a new correspondence circle, the Gremolo (Sonia GREene, James F. MOrton, and H. P. LOvecraft), similar to those that Lovecraft already participated in:

By the way—it looks as though the Galpinian cast-asides are going to found a scholastic salon of their own, for this a.m. there blew into the Magnolia P.O. two bulky duplicate letters for Mme. G. & myself, from good ol’ Mocrates [James F. Morton] in Madisonium. He calls the new circle the Gremolo, & doubtless intends it as the standard refuge for rejected second-raters. […] Mo gives a cruel anecdote in the new Gremolo, which you must not repeat to SL on pain of death.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Alfred Galpin, 30 Jun 1922, Letters to Alfred Galpin & Others 226

No letters from Lovecraft to the Gremolo (or Morton or Sonia to the Gremolo) have surfaced, so it’s not clear how long it lasted, or if it differed substantially from Lovecraft’s other letters to Morton. Judging by Lovecraft’s letters to other such correspondence groups, they would probably have focused on literature, philosophy, and amateur affairs of mutual interest. Certainly, Lovecraft would not include anything intimate to letters intended for both Morton and Sonia.

Lovecraft and Sonia had seen quite a bit of each other in those early months of 1922, and Sonia noted:

After my vacation in Magnolia we each went to our respective homes. Then our more intimate correspondence began which led to our marriage.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 138

We have very little idea of what this “intimate correspondence” might have looked like or consisted of. Some of it was no doubt cajoling Lovecraft into additional visits; he went down to New York to visit her again in September 1922. Some of it must have discussed the possibility of marriage, and we have a surviving excerpt from such a letter, which Sonia incorporated into an article as “The Psychic Phenominon [sic] of Love”; this was eventually published, at least Lovecraft’s portion, as “Lovecraft on Love” in the Winter 1971 issue of the Arkham Collector. Sonia notes on the manuscript:

It was Lovecraft’s part of this letter that I believe made me fall in love with him; but he did not carry out his own dictum; time and place, and reversion of some of his thoughts and expressions did not bode for happiness.

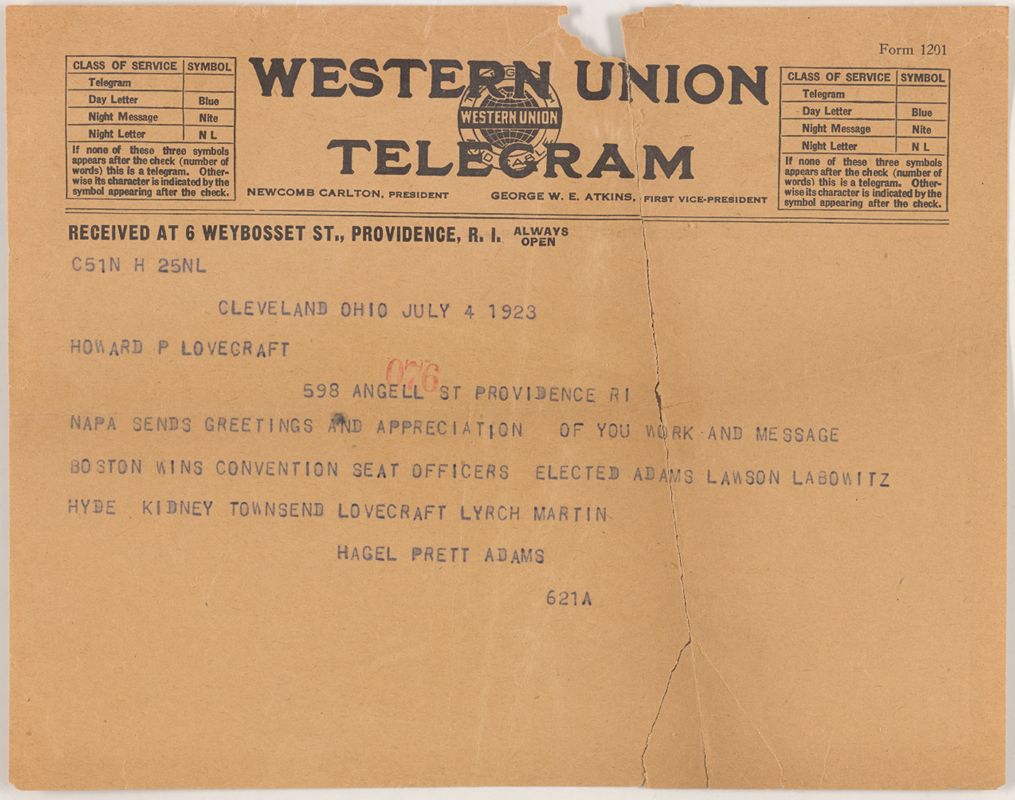

The September 1922 visit was another success; Sonia and Lovecraft both wrote to Providence encouraging the aunts to come, and the younger aunt Annie E. P. Gamwell took them up on it. When Lovecraft and his aunt returned to Providence, Sonia found opportunities to visit in October and November, and when passing through in July 1923 she dragged Lovecraft along to a visit to Narragansett Pier. All these visits suggest a deepening relationship, but they were no doubt precipitated and followed by letters and postcards. Another subject would rear its head in 1923: Sonia was elected president of the United Amateur Press Association.

I got a note from Mrs. Greene asking to be relieved of the unexpected & cataclysmic presidential burden, but have written back urging her to hang on for dear life until Saas, P. J. C., & I get the matter thrashed out. If she resigns, the office will automatically fall on that impossible creature Mazurewicz—1st Vice-Pres.—which of course means utter chaos. You see we have a definite presidential succession, unlike The National with its need for directorial action. But—I shall not try to do anything, or to ask S. H. G. to serve, unless I am absolutely assured of the active & strenuous cooperation of Daas & Campbell.

—H. P. Lovecraft to James F. Morton, 23 Sep 1923, Letters to James F. Morton 55-56

Sonia of course had a full-time job, and probably little to no idea what being president of an amateur press association entailed; no doubt her initial generosity had encouraged the votes for her. We have little idea of her personal life during this period, but she was traveling frequently and it appears that it was during this time period (1921-1923) that her daughter Florence (who Lovecraft had met during the 1922 visit) left her home to work as a journalist.

Weird Tales debuted in 1923, and Lovecraft immediately formed a rapport with the editor Edwin Baird and the proprietor J. C. Henneberger. He sold several stories, including Sonia’s “The Horror at Martin’s Beach,” which appeared in the October 1923 issue as “The Invisible Monster”—which was no doubt discussed between them. Sonia’s accounts of this period suggests that the correspondence was prolific and heavy:

I well know that he was not in a position to marry, yet his letters indicated his desire to leave his home town and settle in New York. […]

After two years of almost daily correspondence—H. P. writing me about everything he did and everywhere he went, introducing names of friends and his evaluation of them, sometimes filling 30, 40 and even 50 pages of finely written script—he decided to break away from Providence.

During our few years of correspondence and the many business trips I took to New England I did not fail to mention many of the adverse circumstances that were likely to ensure, but that we would have to work out these problems between us, and if we really cared more for one another than for the problems that might stand in our way, there was no reason why our marriage should not be a success. He thoroughly agreed.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 136

Strange as it may sound, Lovecraft’s prospects at this point were positive: he had a lucrative ghost-writing assignment doing a story for Houdini for Weird Tales (“Imprisoned with the Pharaohs”), there were possibilities for remunerative literary work in New York City, he was doing some considerable revision work for David Van Bush, Sonia had her well-paying job and savings, many of his friends were in New York…while the whole thing was a gamble, there were reasons to be optimistic.

So on 3 March 1924, Sonia H. Greene became Sonia H. Lovecraft.

Being, like me, highly individualised; she found average minds only a source of grating and discomfort, and average people only a bore to escape from—so that in our letters and discussions we were assuming more and more the position of two detached and dissenting secessionists from the bourgeois milieu; a source of encouragement to each other, but fatigued to depression by the stolid grey surface of commonplaceness on all sides and relieved only by such isolated points of light as Sonny Belknap, Mortonius, Loveman, Alfredus, Kleiner, and the like.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Lillian D. Clark, 9 Mar 1924, Letters to Family and Family Friends 1.102

When Sonia and Howard were living together, they had no need to writer letters to one another. Much of what we know about their marriage during this period comes from diary-like entries in Howard’s letters to his aunts, and occasionally to others. A full account of their marriage is beyond the scope of this article, but it is notable that their period of cohabitation was not long. Health troubles landed Sonia in the hospital; financial troubles struck them as well—Sonia’s high paying job was gone, a hat shop venture failed, Howard’s efforts to secure employment failed consistently, and the new couple were forced to economize—and by December 1924, Sonia had determined that she had to take a position in the Midwest.

Howard would not follow.

Our marital life for the next few months was spent on reams of paper washed in rivers of ink.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 140

H. P. Lovecraft’s letters during 1925-1926 give our only insight into their married life. For most of that period, Howard remained in New York while Sonia worked in Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Chicago, returning to New York for visits whenever she got the opportunity. His letters to his aunts give the flavor of what must have been their almost exchanges:

Her last letter to me before returning sheds so much light on the hard conditions preceding her loss of the post, that I think I will enclose it for you & L D C [Lillian D. Clark] to read.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Annie E. P. Gamwell, 26 Feb 1925, Letters to Family and Family Friends 1.254-255

In a letter just recd., S H suggests that I drown the memory of my losses in a trip to Saratoga the middle of next month, whilst her employers are away—possibly working a call on nice old Mr. Hoag.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Lillian D. Clark, 28 May 1925, Letters to Family and Family Friends 1.301

Had a letter from S H yesterday, saying that Mrs. Galpin didn’t shew up in Cleveland at all! She’s quite worried, imagining all sorts of kidnappings, wrecked, & such like; but I fancy Mrs. G. was merely too tired out to relish the Youngstown change of cars, so went straight home to Chicago.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Lillian D. Clark, 27 Aug 1925, Letters to Family and Family Friends 1.367

Another letter from S H, whose prospects seem unfortunately black. Conditions in new place are uncongenial owing to rivalry of those who sell on occasion. She advises me to move—but I stand by my vote & the results of the election & stay!

—H. P. Lovecraft to Lillian D. Clark, 22 Oct 1925, Letters to Family and Family Friends 1.457

For his own part, Lovecraft’s responses seemed to include terms of endearment:

For nearly two years our almost daily exchanges of letters consisted of each assuring the other of real appreciation. On his part it was a case of “Oh, it isn’t you, my dear, it is all the others.” “You don’t know how much I appreciate you!” etc. etc.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 149

Howard’s initial enchantment with New York had by this time soured. He had no job and was supported by money given to him by his absent wife and a few dollars from his aunts, living in a neighborhood of the city swiftly becoming a slum, and someone broke into his rooms and stole his clothes—and Sonia’s wicker valise. His letters to others showcase his increasingly xenophobic and racist sentiments regarding New York and its denizens, particularly Jews, immigrants, and Harlem. Profoundly unhappy, his aunts suggested he return home to Providence, and Sonia supported the move:

S H endorses the move most thoroughly—had a marvellously magnanimous letter from her yesterday. She may be in Cleveland 2 wks. Or more to come, so there’s no need of bothering her with the packing.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Lillian D. Clark, 1 Apr 1926, Letters to Family and Family Friends 2.585

For the next three years, Howard would remain in Providence, sometimes visited by Sonia, sometimes traveling down to New York to visit with her, sometimes for weeks as when Sonia again attempted to open a hat shop in Brooklyn in 1928. During such periods when they were together, their correspondence must have ceased, or perhaps been limited to cards as Lovecraft took the opportunity to travel to places within reach of New York in search of colonial antiquities. However, this shop failed too, and Lovecraft returned to Providence.

For the next several months we again lived in letters only. He was perfectly willing and even satisfied to live this way, but not I. I began urging a legal separation, in fact, divorce. […] I told him I did everything I could think of to make our marriage a success, but that no marriage could ever be such in letter-writing only; that a close propinquity was necessary for a true marriage. Then he would tell me of a very happy couple whom he knew, where the wife lived with her parents, in Virginia, while the husband lived elsewhere for reasons of illness, and that their marriage was kept intact through letters. My reply was that neither of us was really sick and that I did not wish to be a long-distance wife “enjoying” the company of a long-distance husband by letter-writing only.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 140-141

Howard protested, but eventually acceded to Sonia’s request. No-fault divorce was not available, but under Rhode Island law Howard could file for divorce on the cause of Sonia having abandoned the marriage, and her failure to respond would be proof of the abandonment. While this legal fiction was pursued, Howard failed to sign and file the final decree—so that they were technically still married, even though Sonia believed they were divorced, and Howard uniformly presented himself as such, in the rare occasions when he mentioned his marriage in later years.

After a year and a half of almost daily letter-writing, back and forth, we were finally divorced in 1929, but we still kept up correspondence; this time it was entirely impersonal, but on a friendly basis, and the letters were far and few between until in 1932 I went to Europe. I was almost tempted to invite him along but I knew that since I was no longer his wife he would not have accepted. However, I wrote to him from England, Germany and France, sending him books and pictures of every conceivable scene that I thought might interest him.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 141

Most of our information on Sonia’s life and her correspondence with Howard came through his letters. Now that they were divorced, their correspondence waned, and Lovecraft’s skittishness to talk about his marriage leads to gaps in the record. One rare reference on their correspondence from 1929-1930:

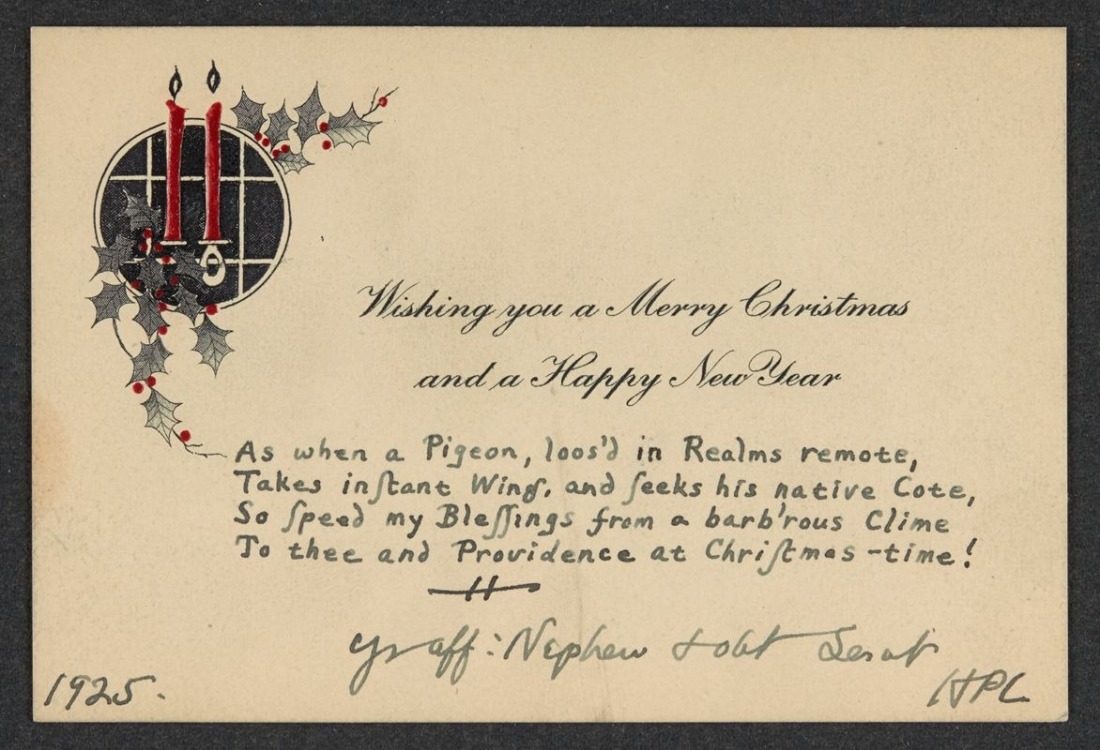

No—you hadn’t previously mentioned the relay’d greetings from the quondam Mme. Theobald; an incident which prompts the usual platitude concerning the microscopic dimensions of this planetary spheroid. My messages from that direction during the past two years have been confin’d to Christmas & birthday cards, but if occasion arises to exchange more verbose greetings, I shall assuredly add your respects & compliments to my own.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Alfred Galpin, c. Sep 1930, Letters to Alfred Galpin & Others 264

There must have been periods of greater activity; during Sonia’s 1932 trip to Europe, which led to Lovecraft compiling and revising her notes into a travelogue: “European Glimpses.” She wrote for him to join her in Connecticut in 1933. It may have been at this time that “Alcestis: A Play” was written, if not earlier. It was their last meeting.

After the Hartford and Farmington visit I did not see Howard again, but we still corresponded, on and off, after I came to California; it was here that I soon met Dr. Davis and remained there.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 145-146

Sonia H. Greene married Nathaniel A. Davis in 1936. It is not clear if she ever informed Lovecraft of the marriage, or if by that point they had fallen completely out of touch. Lovecraft’s lists of postcards sent from his Southern travels do not include entries for Sonia. She was apparently not informed of his death by his surviving aunt, Annie E. P. Gamwell, or by any of their mutual friends at that time, and did not learn about it until about a decade later, probably after the death of her third husband in 1946.

As in many cases when discussing Lovecraft’s correspondence, we do not have Sonia’s own letters to Lovecraft to go by. Whether he choose not to keep them or whether he did and they were not preserved after this death is unknown. Certainly, such intimate correspondence as a man might have with his wife might not be something Lovecraft wished preserved for posterity. However, unlike most of his other correspondents, we don’t have almost anything of Lovecraft’s side of the correspondence either.

In her memoir, Sonia states:

I had a trunkful of his letters which he had written me throughout the years but before leaving New York for California I took them to a field and set a match to them. I now have only the one in the Rainbow and one which I received from him after I returned from Europe. But there are still about a dozen picture postal cards that he sent me before our marriage, during and afterward. Some are still of some interest.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 145

As mentioned, Sonia had been largely if not completely out of contact with the world of things Lovecraftian since they parted in 1933. She was not immediately aware of his death, or of the efforts to preserve and publish his fiction and letters, the appointment of R. H. Barlow as his literary executor, the foundation of Arkham House for that purpose in 1939 by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei, or the beginnings of critical and biographical efforts in works such as W. Paul Cook’s In Memoriam: Howard Phillips Lovecraft (Driftwind Press, 1941) and Winfield Townley Scott’s “His Own Most Fantastic Creation: Howard Phillips Lovecraft” (1944). Ultimately, she was made aware of Lovecraft’s demise, posthumous fame, and began to reconnect with friends like Samuel Loveman.

Whether prompted by a friend or on her own initiative, Sonia composed a memoir of her late husband, the raw manuscript of what would become “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” and read part of it to August Derleth in New York in 1947. According to Derleth’s account:

Meanwhile, did I tell you Sonia Lovecraft Davis turned up with some laughable idea of cashing in on HPL’s “fame” and the desire to publish a “frank” book, entitled THE PRIVATE LIFE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT, and quoting generously from his letters. She read me part of the ms. in New York, and in it she has HPL posing as a Jew-baiter (she is Jewish), she says she completely supported HPL for the years 1924 to 1932, and so on, all bare-faced lies. I startled her considerably when I told her we had a detailed account of their life together in HPL’s letters to Mrs. Clark. I also forbade her to use any quotations from HPL’s letters without approval from us, acting for the estate. I told her by all means to write her book and I would read it, but it was pathetically funny; she thought she could get rich on the book. She said it would sell easily a million copies! Can you beat it! I tried to point out that a biographical book on HPL by myself, out two years, had not yet sold 1000 copies, and that book combined two well-known literary names. She thought she should have $500 advance on her book as a gift, and royalties besides! I burst into impolite laughter, I fear.

—August Derleth to R. H. Barlow, 23 Oct 1947, MSS. Wisconsin Historical Society

One salient point is “quoting generously from his letters.” Arkham House had begun the process of collecting and transcribing letters from Lovecraft’s correspondents for the Selected Letters project, but the first volume would not be published until 1964. The letters that Sonia was quoting must therefore have still been in her possession at least as late as 1947.

Post-World War II, and the exposure of the horrors of the Holocaust, public antisemitism was a vastly different manner than it had been during the interwar period. Derleth’s comments shows he was aware of the potential difficulty if Lovecraft’s antisemitism became well-known. While he did not necessarily speak for Lovecraft’s estate, he had received permission from Lovecraft’s surviving aunt Annie E. P. Gamwell to work with Barlow to publish Lovecraft’s work, and Derleth used this as license to be very protective of both Lovecraft’s intellectual property and his image.

Some correspondence from Sonia survives from this period that sheds light on what happened:

Am I to understand that letters HPL had written to me subsequent to our marriage and those he wrote to me afterwards are not my own private property to do with as I choose? That I must not use them in any way I wish? I am not using material he may have written to some else, only that which he has written to me and for; such as my stories & poems revised by him. Do these, too, belong to you?

—Sonia Davis to August Derleth, 13 Sep 1947, MSS. John Hay Library

To be clear: the writer of a letter still has copyright of the contents, even if physical ownership of the letter belongs to someone else. This seems to be the tack that Derleth was taking: in the pretense that he represented Lovecraft’s estate, he was forbidding her from quoting Lovecraft’s correspondence. This was technically a bluff, since Derleth had no such authority…but legal bluster can be useful to a canny businessman. Derleth must have replied in the affirmative, since Sonia wrote:

So upon reflection I wrote to Mr. Derleth telling him I would have my own publisher do the work and that I would use my story of the “Invisible Monster” as revised by H.P. of mine first as well as some very personal letters and poems of his revision.

In reply he shot back a spec. del. letter that all HP. material belong to the estate of H.P.L. and that “Arkham House” (ie. he) alone had full legal rights to its use; and that I was likely to find that the could would restrain the sale of the work, would confiscate & destroy it.

I have written him stating that I had already offered the material to you, but that I may have to retract the offer if I am to be punished for using letters that were addressed to me personally.

Perhaps I am quite ignorant of the law but I cannot see how these can belong to the Lovecraft estate, to Mr. Barlow (as he stated) or to himself! Personally I no longer feel an interest in my past. Other interests have developed since then. However, because Mr. D. & you and others clamored for HPL’s private life with me, I thought it might be a source of income, and at the same time tell some truths that would throw more light on his character and perhaps on his psychology.

Since I do not know the law regarding these matters and as I have no money to start any “fights” it might be the better part of valor to drop the matter altogether, since while I do not fear Mr. D’s veiled threats and open intimidation I’m not in a position to fight.

Mr. D’s method of “high pressuring” me into doing what he wants is not to my taste. It would be interesting to contact the county clerk in Providence and make sure my reasons to believe that H.P. died intestate. If so, how does the property belong to Barlow and Derleth?

—Sonia Davis to Winfield Townley Scott, 13 Sep 1947, MSS. John Hay Library

Legal intimidation is a tactic because it works; by this point Sonia was 60 years old and was apparently still in, or had re-entered, the workforce after the death of her third husband. Whether or not one chooses to believe that Derleth was acting in what he thought was Lovecraft’s best interests, his accounts of the affair at the time do not reflect well on him:

I’ve heard from various sources in town that Lovecraft’s wife has suddenly put in an appearance and is causing somewhat of a rumpus. Is this true, or is it, as usual, the kind of ill thought out gossip that is prevalent among the inept citizens of the L. A. Fantasy Society?

—Ray Bradbury to August Derleth, 19 Nov 1947, MSS. Wisconsin Historical Society

Lovecraft’s wife did turn up; she is now a Mrs. Sonia Davis, the widow of the husband (no. 3) she had after HPL. She wrote a biography called THE PRIVATE LIFE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT, and wanted to incorporate a lot of his prejudices as if they were major parts of his life, seen through her Yiddish eyes; she also wanted to include letters of Lovecraft, but we pointed out that the only way she could do that would be with our permission first. We have heard nothing further from her, though I had a talk with her in New York City.

—August Derleth to Ray Bradbury, 21 Nov 1947, MSS. Wisconsin Historical Society

Given the circumstances, Sonia made a possibly fateful decision:

Here is what I propose to do with the H.P. material. I’ll send you my version of his biography but not his letters. If you find this sufficiently interesting to review for your newspaper you may use it for whatever monetary consideration it is worth to you.

You may revise and edit it to suit yourself, of course, adhering to the general context, but as I shall wish to use it later for publication I trust there will be no trouble in so doing. That is, I wish to sell the story but not the rights to it. Nor do I wish Derleth to make use of any part of it without my permission.

He wants the story and the letters. And as he has stated that the letters belong to the H.P. estate he would probably copy them and return the original.

The entire story is not yet all typed but if you are still interested I shall type it and you may use what you wish.

—Sonia Davis to Winfield Townley Scott, 4 Nov 1947, MSS. John Hay Library

“The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” that we have today is a meandering document, often filled with random remembrances that occur on the page as they occurred to Sonia. Scott heavily edited this manuscript, reorganizing it into a basically chronological narrative of the marriage, retaining most of Sonia’s language and insights, but like the manuscript we have it contains few direct quotes from Lovecraft. The memoir was published as “Howard Phillips Lovecraft As His Wife Remembers Him” published in the Providence Journal 22 Aug 1948. A notable omission in this version of Sonia’s memoir is that it makes no reference to burning a trunk of letters. She does show continued anxiety about the subject:

Derleth told me that I cannot & must not quote H.P. not only from his letters but not even anything he said that might not have been in letters. So that if you can manage to paraphrase, it may be alright. Otherwise Derleth will stop at nothing, to hurt me, even if he had to take me into court. And I’m not in a position to quarrel with him and win, for I have no income other than what I earn.

—Sonia Davis to Winfield Townley Scott, 6 Aug 1948, MSS. John Hay Library

Derleth had no way of knowing Sonia had submitted the manuscript to Scott, and apparently had not heard from her in some weeks after her had made his legal threats in early September 1947. So he wrote to her:

I have so far had no reply to my letter of 18 September. Meanwhile, I hope you are not going ahead regardless of our stipulations to arrange for publication of anything containing writings of any kind, letters or otherwise, of H. P. Lovecraft, thus making it necessary for us to enjoin publication and sale, and to bring suit, which we will certainly do if any manuscript containing works of Lovecraft do not pass through our office for the executor’s permission.

You will be interested to know that we now have in Lovecraft’s own letters to his aunts a complete and detailed account of how things went during his entire married life.

—August Derleth to Sonia Davis, 21 Nov 1947, The Normal Lovecraft 29

Derleth was describing the diary-entry letters, some of which do describe their married life in great detail, although certainly leaving out many things a man might say to his wife, and vice versa. Sonia apparently consulted her friends about what to do.

Enclosed is a letter from (August) Derleth. Do you think he is “shooting in the dark”? Bluffing? I answered, telling him as long as he has H.P.’s letters to his aunts he no longer needs my version of the story.

—Sonia Davis to Samuel Loveman, 30 Nov 1947, The Normal Lovecraft 28

Some of the Sonia/Derleth correspondence is not accessible to scholars at this point. Although the letters for the critical period at the end of 1947 exist, they are apparently in private hands. However, Lovecraft and Derleth scholar John D. Haefele quoted one such letter in one of his publications:

You are at perfect liberty to destroy those letters from Lovecraft without showing them to anyone. …. You are not at liberty to publish any part of them without our permission…

—August Derleth to Sonia Davis, 19 Dec 1947, Lest We Forget 15

This strongly suggests that the holocaust of letters Sonia describes may actually have happened at the end of 1947 or early 1948. There is apparently a reference to burning the letters written on the back of Derleth’s letter of 1 October 1965 (Arkham House Archive), but it is difficult to believe that Sonia would have waited until 1965 to burn a trunk of letters: she suffered a heart attack in Summer 1948, and in 1960 she broke her hip, forcing her to move into a nursing home. Late 1947 or early 1948 may have been the last period when Sonia was physically able to accomplish such destruction without assistance.

Sonia and Derleth reconciled, her Lovecraft memories and revisions printed in Arkham House books (except for Alcestis and European Glimpses), and they remained good friends until her death. Even with the destruction of these years of correspondence, one or two odd survivals apparently remained. “The Psychic Phenominon [sic] of Love” being one:

Before burning 400+ letters of H.P.L.’s I copied part of one, adding my own version. After many years, I came across it, and am sending you a copy for permission to try to sell it. I do not know where I can sell it; but if I may use it and am unable to sell it, I will use it as part of my biography which has been invited by the Library of Special Collections at Brown University which is publishing my late husband’s works, N. A. Davis.

—Sonia Davis to August Derleth, 29 Nov 1966, MSS. Wisconsin Historical Society

As for the cards that Sonia had sent to Lovecraft over the years, they suffered a similar fate:

Mrs. Gamwell also gave the children about a hundred picture postcards that Sonia had mailed to Howard. These all held loving, spirited messages to H.P.L. from his sweetheart in New York. Not knowing their possible value in the far-away future, I did not hold on to any of these cards bearing Sonia’s signature, written in her breezy, happy handwriting. It was plain to be seen, from the messages on the cards, that this pretty woman of writing ability—among her other gifts—really liked H.P.L.! And the strange part of it all was that he had not once mentioned his love affair to us…and we were his very good friends.

The children played for hours with the cards, and they eventually went the way all children’s toys go…in the ash-heap!

—Muriel E. Eddy, The Gentleman From Angell Street 17

That is essentially the end of what we know for Sonia H. Greene’s letters to H. P. Lovecraft. “Lovecraft on Love” and “Nietzscheism and Realism” are the major letter-excerpts that remain; the former has not been reprinted as far as I can determine, while the latter is available in several collections, notably Arkham House’s Miscellaneous Writings and the Necronomicon Press facsimile of The Rainbow.

In some of H. P. L.’s letters to me he often spoke of reincarnation, but I do not think he believed in it.

—Sonia H. Davis, “The Private Life of H. P. Lovecraft” in Ave Atque Vale 150

We are so fortunate, as readers and scholars, that so many of Lovecraft’s letters have survived. Not only for what they tell us about Lovecraft himself, but about the people he interacted with, the lives and relationships he had with women like Sonia H. Greene. Through his surviving letters to his aunts and friends, we have a deeper, more complete idea of his marriage and his critical formative period in New York. She was a critical part of his life, and we would not know as much as we do about Sonia without his letters.

Yet, there is always that regret that we couldn’t know more. That decisions were made which cost us that inside glimpse at her life with Lovecraft, her love affair with a man who, while he would go on to become a legend, was at once just a husband trying to make the best of it in the big city…and things didn’t work out. They grew apart. The letters and postcards just stopped one day.

As they must. No one lives forever, no relationship lasts forever. Normally when we look at the correspondence with Lovecraft, the story we tell really stops when Lovecraft dies; but Sonia’s story went on…and her story and his are intimately intertwined, even in death.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard & Others (2019) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014).