As for fortune-telling—I won’t try to argue the matter, but believe your continued studies in the various sciences will eventually cause you to abandon belief. Authentic psychology is one thing, but irresponsible prophecy is another.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Nils Frome, 19 December 1937, Letters to F. Lee Baldwin &c. 348

After a successful crowdfunding, Sara Bardi’s Eldritch Tarot has been unleashed upon the world—but this is not the first and will certainly not be the last tarot to take inspiration from H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos. To review this deck properly requires a certain understanding of what tarot is, where it comes from, how it has developed over the centuries—and how and why Lovecraftian tarots became a thing.

What has come to be the “standard” deck of playing cards in the English-speaking world are has ten pip cards (numbered Ace to 10) and three court cards (Jack, Queen, King) in four suits (typically diamonds ♦, spades ♠, hearts ♥, and clubs ♣). These 52 cards are often augmented by two “Jokers,” who have no suit and often are used as wild cards for some games. The exact number of cards, suits, etc. have varied over the centuries and in different countries, through a long and not always well-documented evolution.

Playing cards appear to have entered Italy from trade with the Mamlūk Empire in about the last quarter of the Fourteenth century (A Cultural History of the Tarot 8-9, 12-13). These early Mamlūk decks had four suits (Swords, Coins, Cups, and Polo Sticks); when translated into a European cultural milieu, where polo was less popular, the fourth suit became Batons—and over time, as the deck designs proliferated throughout Europe, different countries and places developed slightly different names and symbols. So the Italian suit of Coope (Cups) became Herzen (Hearts) in German, and Rosen (Roses) in Switzerland; Italian Denari (Coins) became Oros (Gold) in Spanish, Schellen (Bells) in German, Diamonds in English. Spade (Swords) became Spades in English, and so on forth.

Tarot cards are a branch of the evolution of the “standard” deck, and were intended to play games. A typical contemporary tarot deck has four suits (typically Cups, Coins, Swords, and Batons), each with pip cards (A to 10) and four court cards (Knave, Knight, Queen, King); twenty-one trumps, and a Fool card, which gives a total of 78. As with the “normal” playing deck, this was not set in stone, and there were many variations, especially considering the suits, the number and type of trumps, how they were ordered, etc. The trumps were incorporated for trick-taking games: whoever had the higher trump took the trick. Contemporary trick-taking games like Bourré played with normal playing carts designate one of the suits as trumps at the start of the game. In contemporary uses for divination & magic, the trumps (including the Fool) are typically called the Major Arcana, while the pip-cards and court-cards constitute the Minor Arcana.

Tarot decks begin to show up around Milan in the first half of the 15th century (A Cultural History of the Tarot 33-39), and spread and developed from there across Europe for several centuries. As might be expected, there were many local variations, some of which continued on and others which petered out. Eventually, certain consistent styles of decks became dominant: by the about the beginning of the 17th century, the most popular style of tarot deck in France was the Tarot de Marseille. Cartomancy, or divination by shuffling and revealing the cards, appears to have begun in the mid-to-late 18th century in France, and was popularized by the publication of Etteilla, ou manière de se récréer avec le jeu de cartes in 1770 (A Cultural History of the Tarot 93-95).

The system in Etteilla was not tarot-card reading as we know it today. The author Jean-Baptiste Alliette made a variation on the Tarot de Marseille (he used a piquet pack, which had the pip cards from 2 to 6 removed, plus the addition of an “Etteilla” card to represent the asker.) While Alliette was focusing on tarot for fortune-telling as a past-time, French occultist Antoine Court de Gébelin began to interpret the tarot trumps as occult symbols, and worked them into his system, claiming that they were a corrupted version of the Egyptian Book of Thoth (Egyptomania was prominent in France at the time, and would continue to be popular into the 19th century, which can be seen in developments such as Egyptian Freemasonry). De Gébelin surmised that tarot had been brought to Europe by the Romani (popularly, though pejoratively, called “gypsies,” and who were believed by some to be displaced Egyptians), and the association of tarot and the Romani would continue in the popular consciousness for centuries (A Cultural History of the Tarot 102-109).

By the time Alliette began selling the Etteilla and tarot decks for fortune telling, tarot as a card game had been defunct in Paris, though still popular in other parts of Europe. Building off of the work of de Gébelin and Alliette, Éliphas Lévi Zahed revised and incorporated the symbolism of the tarot trumps into his systemic works of ceremonial magic, including Dogme et Rituel de la haute magie (1854-1856), La Clef des Grands Mystères (1861), and Histoire de la magie (1860)—the latter of which, in the English translation, would eventually be read by H. P. Lovecraft. Lévi’s system brought together medieval European systems of correspondences, the zodiac, kabbalah, and the tarot trumps (A Cultural History of the Tarot 111-117).

While Lévi allowed that tarot was useful for cartomancy, his incorporation of tarot into a system of magic opened up the tarot to be used in other magical operations—and the alterations made in the tarot decks of Lévi, Attelier, and other popularizers like Papus (Gérard Anaclet Vincent Encausse) in the correspondences, numbering, and iconography of the trump cards encouraged others to make further alterations. There were many different occultists throughout Europe who developed the tarot as a means of divination or incorporated it into their occult philosophy—including Helena Blavatasky—but to focus on the path that leads to Lovecraftian tarots, the work of Lévi & co. was particularly influential on a small a group of English ceremonial magicians known as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (A Cultural History of the Tarot 126-136; A History of the Occult Tarot 76-90).

One of the founders of this society, Samuel Lidell Macgregor Mathers, published The Tarot: Its Occult Singification, Use in Fortune-Telling and Method of Play (1888) the same year that the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn came into existence. The order was organized along the lines of a Freemason lodge (albeit accepting both men and women) with three degrees of initiation, and the system they used was based on a Cipher Manuscript, and included instruction on using the tarot for magical operations. While drawing heavily on Attellier, Lévi, & Papus and still recognizably based on the Tarot of Marseille, the Cipher Manuscript again made several changes in the associations & numbering of the trumps. Among the initiates of the order were Arthur Machen and his friend Arthur Edward Waite, Algernon Blackwood, Aleister Crowley, Dion Fortune, William Butler Yeats, and William Sharp; a good book on some of these is Talking to the Gods: Occultism in the Work of W. B. Years, Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, and Dion Fortune by Susan Johnston Graf. Though the Order was relatively small, it had an outsized influence on contemporary occultism. The system of ceremonial magic that the Cipher Manuscript and related teachings described, and the tarot deck needed for it, would inform the decks and systems of its initiates (A History of the Occult Tarot 91-113).

In particular, in 1909 Arthur Edward Waite designed a deck, with art provided by Pamela Colman Smith (also known as “Pixie”). Waite based his iconography and numbering on the Order’s, with a few changes, but Smith apparently took inspiration from a 15th century tarot called the “Sola-Busca” deck. Unlike most tarot decks which left the pip cards relatively plain, this deck included full illustrations for all cards, which Pixie followed in her deck. The resulting deck, which was published by the Rider and is popularly (if inaccurately) known as the Rider-Waite tarot has become the most popular and influential tarot deck of the last century, with its suits (Wands, Pentacles, Cups, Swords), trump names and numbering, and iconography becoming iconic (A Cultural History of the Tarot 144-148, A History of the Occult Tarot 127-141).

The Waite-Smith tarot deck was widely published after World War II, and like ouija boards and other aspects of spiritualism and occultism found a new generation of adherents during the New Age movement in the 1970s. Yet before that happened, tarot was already a part of Lovecraftian occultism.

Aleister Crowley is a now-elderly Englishman who has dabbled in this sort of thing since his Oxford days. He is, really, of course, a sort of maniac or degenerate despite his tremendous mystical scholarship. He has organised secret groups of repulsive Satanic & phallic worship in many places in Europe & Asia, & has been quietly kicked out of a dozen countries. Sooner or later the US. (he is now [in] N.Y.) will probably deport him—which will be bad luck for him, since England will probably put him in jail when he is sent home. T. Everett Harré—whom I have met & whom Long knows well—has seen quite a bit of Crowley, & thinks he is about the most loathsome & sinister skunk at large. And when a Rabelaisian soul like Harré (who is never sober!) thinks that of anybody, the person must be a pretty bad egg indeed! Crowley is the compiler of the fairly well-known “Oxford Book of Mystical verse”, & a standard writer on occult subjects. the story of Wakefield’s which brings him in (under another name, of course) is in the collection “They Return at Evening,” which I’ll lend you if you like.

—H. P. Lovecraft to Emil Petaja, 5 April 1935,

Letters with Donald and Howard Wandrei and to Emil Petaja 420-421

Aleister Crowley is probably the most infamous former member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and expanded and changed its teachings in his subsequent magickal organizations the Argentum Astrum (A∴A∴) and the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.). As part of his occult publications, Crowley developed his own variant of the tarot deck, often called the Thoth deck (A Cultural History of the Tarot 137-142, A History of the Occult Tarot 142-156). Crowley’s final secretary and acolyte at the time of his death was a young man named Kenneth Grant, who went on to continute to develop and practice Crowley’s magickal system of Thelema, and to publish his own exegesis of the Golden Dawn-derived system. What sets Grant apart from from Crowley is that he directly incorporated fictional elements from the work of Arthur Machen and H. P. Lovecraft into his system in books like The Magical Revival (1972) and eventually inspired artist-occultist Linda Falorio to create the Shadow Tarot (A History of the Occult Tarot 310-311). Other occultist such as Nema Andahadna also used tarot in their Crowley-derived magickal systems. As an example of what this looks like:

One of Crowley’s methods of counter-checking a name or a number was by reducing it to a single number and adding together its component digits, referring the result to a Tarot Key. For example, if a spirit gave as its number 761, this would be checked thus: 7 + 6 + 1 = XIV, the Tarot Key entiled Art; and if the symbols and attributions of this Key were consant with the meaning of the number itself, it offered good ground for assuming that a bona fide spirit had responded to the invocation; but further tests would be necessary if doubt remained. Not only can the disembodied spirit of dead or sleeping people impersonate spirits and work evil by such means, but—which is infinitely more dangerous—extracosmic entities can masquerade as spirits and, if they are not banished before they can gain a foothold in the consciousness of he who invoked them, obsession follows. Austin Spare is the authority on their control; Lovecraft, on the devasation they leave in their wake when they are let loose upon the earth.

—Kenneth Grant, The Magical Revival 110

Grant wasn’t the only magician playing with Lovecraftian occultism, but he was the most prominent working within a syncretic system that incorporated tarot as part of its magical workings, as opposed to works like the George Hay-edited The Necronomicon: The Book of Dead Names (1978), which was styled on the medieval European grimoire tradition…which, of course, did not use the tarot in an occult context because playing cards and tarot cards weren’t introduced until the late medieval period, and then just for gaming. Those interested in a history of Lovecraftian occultism in general are encouraged to pick up The Necronomicon Files by Daniel Harms & John Wisdom Gonce III.

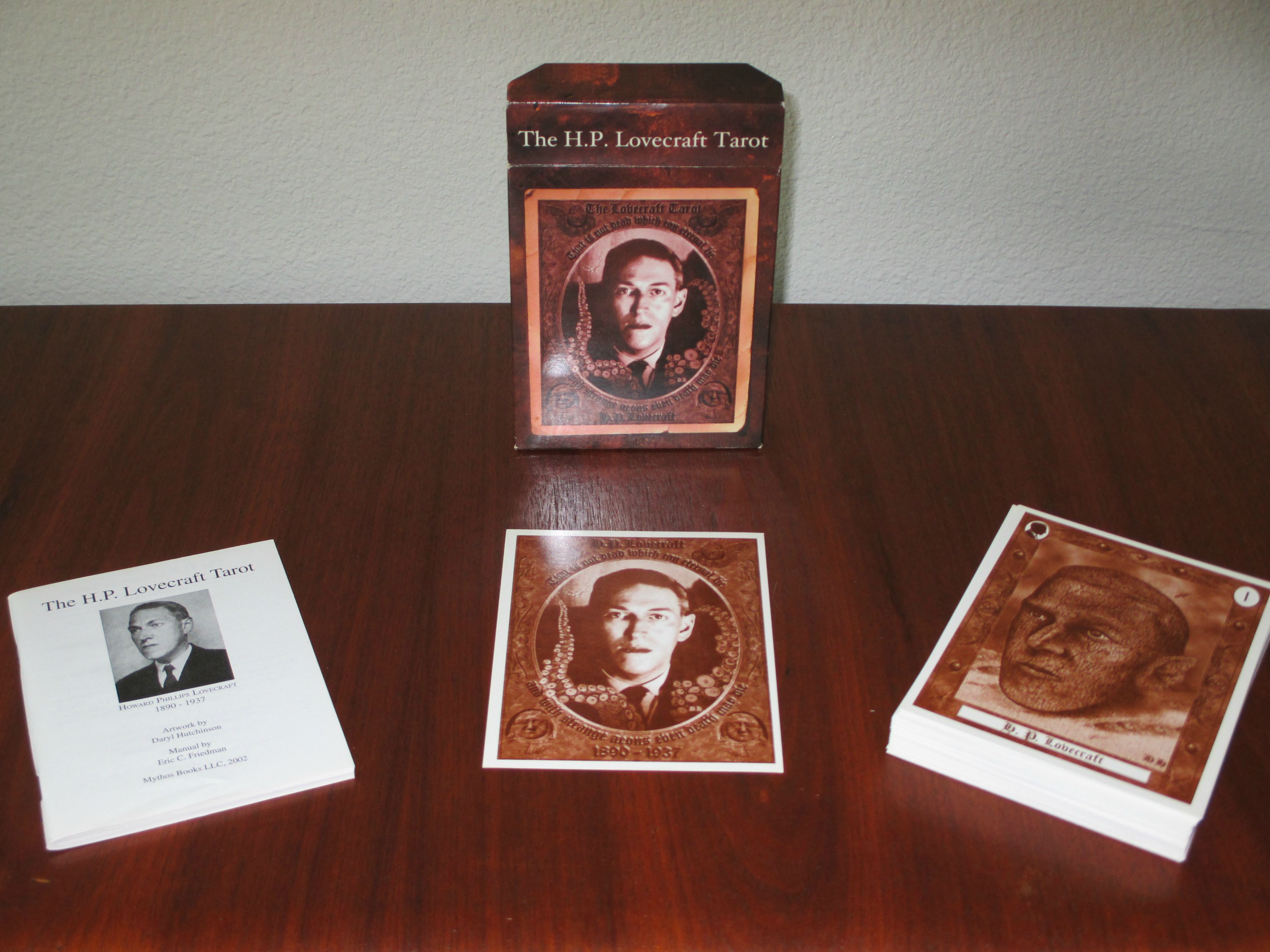

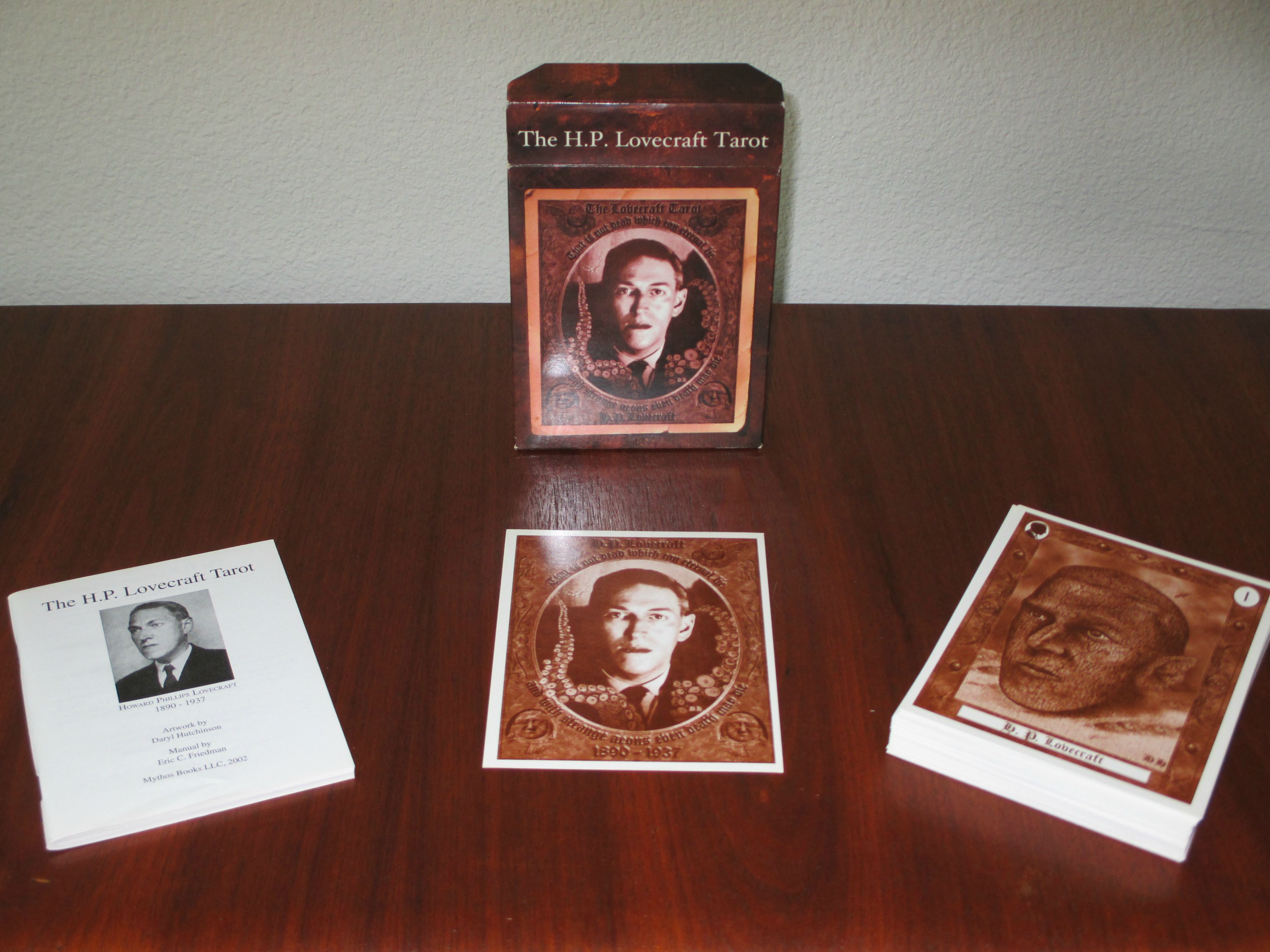

The H. P. Lovecraft Tarot

By the 1990s, would-be occultists could find mass-market paperback copies of the Simon Necronomicon and copies of the Waite-Smith deck in the New Ages shelves of their local bookstore, but there wasn’t really a Lovecraft-specific deck until David Wynn and Daryl Hutchinson came together to publish The H. P. Lovecraft Tarot (Mythos Books LLC, 1997/2002) in two limited editions, which now command high prices on the secondary market. This tarot largely follows the format of the Waite-Smith tarot in geneal form: there are 22 trumps, and the other cards are numbered in descending order and divided into four suits (Man, Artifacts, Tomes, and Sites), with each card depicting something from Lovecraft’s stories. The manual (by Eric C. Friedman) gives readings and a suggested spread, not disimilar from various Attellier-derived popular fortune-telling books. As a deck, it’s obviously intended as a bit of fun without any of the Waite-Smith style symbolism, opting instead for sepia-toned images, and is a product of New Age occultism married to popular culture—but still representing a lot of work!

The H. R. Giger Tarot

Swiss artist H. R. Giger named two of his art collections Necronomicon, and although its particular subjects took little inspiration from Lovecraft, that connection between their work has continued (as discussed in “Elder Gods” (1997) by Nancy Collins). In 1992, the occultist Akron adapted 22 of Giger’s famous paintings into Baphomet: Tarot der Unterwelt, which was released as the H. R. Giger Tarot in English. These cards consist of only the trumps/Major Arcana, as well as a fold-out poster for the spread and a 224-page booklet (in the English edition, the German hardback is 408 pages) on potential spreads and interpretations of the cards. Akron had previously worked on The Crowley Tarot (1995), and shows the influence of Kenneth Grant in designating this a “shadow tarot,” but the purpose is more mystical than magical, less New Age in the sense of occult fun-and-games and more intended as a serious (and very cool-looking) tool for personal introspection and spiritual growth.

The Necronomicon Tarot

In the mid-2000s occult publisher Llewellyn published the “Necronomicon Series” by Donald Tyson, a series of pop-occult books with a Lovecraftian theme, including Tyson’s novel Alhazred: The Author of the Necronomicon (2006), a specious magical biography of Lovecraft, some ersatz grimoires, and in collaboration with artist Anne Stokes a tarot deck and manual: the Necronomicon Tarot (2007). This is a full tarot of 22 trumps and four suits (Discs, Cups, Wands, and Swords). While Stokes’ artwork stands out as effective and creative, this is really little more than a re-skin of the Waite-Smith tarot; so that even though the Minor Arcana all bear full illustrations, the system of planetary and elemental correspondences, the suggested readings, etc. are all basically a version of Arthur Edward Waite’s The Pictorial Key to the Tarot (1911). Any tarot-reader already familiar with other systems can pretty much pick this deck up and use it. In this, Tyson’s tarot is totally in keeping with the rest of his work on the Necronomicon Series: pure pop-occultism.

The Dark Grimoire Tarot

By this point it was easier than ever before for basically anyone to print their own tarot, in a consistent size and relatively high quality. Which is why in 2008 the The Dark Grimoire Tarot by Michele Penko and Giovani Pelosini was published by Lo Scarabeo in Italy. Despite the unassuming English name, this is in fact a multi-lingual deck and three of the alternate titles are Tarocchi del Necronomicon, Tarot del Necronomicon, and Tarot du Necronomicon, just in case you had any doubts what they were about. This is quite literally just the Waite-Smith deck with different art; all the trumps and suits are the same. The book of instructions is split into six languages, and so only amounts to twelve pages for the English text, offering a very simple pentagram-inspired spread and some concise interpretations. If you don’t already know how to interpret tarot cards, this book won’t give you much to go on—but other than that, it isn’t really very different from the Necronomicon Tarot, and both are pretty much just tarot decks as product, rather than a showcase for art or a legitimate attempt at a useful occult tool.

The Book of Azathoth Tarot

The 18th century French occultists declared the tarot deck the Book of Thoth, a legendary tome of magical lore which was encoded into the trumps of the deck; in this postmodern world, an occultist called Nemo has reworked this material into the Book of Azathoth Tarot. The first edition of these cards in 2012 had a really ugly back, but the subsequent edition has a much nicer design. Compared to the previous examples, this might be considered the most “serious” of the Lovecraftian tarots to date. It is a full tarot strongly inspired by the Waite-Smith tarot deck, right down to the same suits and trump names and numbers, and even moreso as it incorporates Hebrew letters, astrological symbols, and Zodiac signs into the iconography, and is obviously closely following some of Smith’s iconic designs, with a Mythos twist.

Which kind of works in its favor, oddly enough. The artwork has a design like medieval woodcuts, with a stark but uniform yellow-and-black color scheme that gives a very clean appearance, and combined with the more classic design gives the deck a more traditional and authentic feel, even though the materials are all completely contemporary. The guidebook (2020) that goes with the deck is sold separately, hardbound and in full color. It is, again, very traditional. This is closer to what a Lovecraft tarot might have looked like if it was made during his own lifetime than anything else yet produced.

Cthulhu’s Vault Tarot Card Set

Released in 2019 with art by Jacob Walker, the Cthulhu’s Vault Tarot Card Set is possibly the ipsissimus of cheap, lazy, and uninspired Lovecraftian reskins of the Waite-Smith tarot. While some of the art isn’t bad and this is a full 78-card deck, that’s damning with faint praise. In the era of cheap printing as sales move away from brick-and-mortar locations and to online marketplaces, this is also the future of Lovecraftian tarot. Anybody with enough raw art and a minimum of design skill can throw together a tarot deck…and have! You can buy the Cthulhu Dark Arts Tarot, Old Whispers Tarot, and the Forbidden Tarot, and no doubt more that I haven’t run across yet.

In an increasingly competitive marketplace, we might expect that a lot of these tarots will fail commercially, and sink out of sight—maybe to reappear on auction websites at fabulous prices, maybe to be remaindered or gather dust at used bookstores and in basements and attics. But with the barrier for entry so low, we might also see a slew of these cheap decks published for the considerable future. While it is ridiculous to assume that any commercial tarot deck is made without an eye toward profit, the lack of care evident in some of today’s tarot decks illustrates how far we’ve come from the roots of the occult tarot, and how seriously folks like Gébelin, Alliette, Éliphas Lévi, Mathers, and Crowley took them. Tarot really has become just a toy for most people.

The Eldritch Tarot

Which brings us to The Eldritch Tarot by Sara Bardi, successfully crowdfunded and published in 2021. Bardi is an Italian artist, perhaps best known for her webcomic Lovely Lovecraft. The Eldritch Tarot comes with no manual, no key to interpretation, but what it does come with is a lot of heart. The occult DNA of the Waite-Smith tarot deck is still there in the names and numbers of the Major Arcana, but that’s largely where it ends. The four suits are denoted by symbols for The Call of Cthulhu (tentacle), Under the Pyramids (broken chalice), The Dunwich Horror (wavy dagger), and At the Mountains of Madness (the pentagram version of the Elder Sign), and every one of the 78 cards features art in Bardi’s characteristic style.

This is closer to the H. P. Lovecraft Tarot than anything else, but there are no pretenses to occultism in Bardi’s tarot. This is the kind of deck where, if you want to dig out the rules for a tarot trick-taking game, you could sit down at a convention and play a couple hands with friends and have a good time. Or if you want to lay out a spread and tell some fortunes, look up the guidelines on the internet or pick up a cheap book from the library. This is a deck that is mostly shorn of tradition, but the art is clean, detailed, and maybe best of all relevant: this is a deck made by a Lovecraft fan, for Lovecraft fans.

Lovecraft and Tarot

Meaningless spotted pasteboards […]

—H. P. Lovecraft to James F. Morton, 3 Feb 1932, Letters to James F. Morton 294

It’s not clear if H. P. Lovecraft ever saw a tarot deck; I’ve yet to find any direct mention of tarot or cartomancy in his published letters or essays. This isn’t vastly surprising: the global popularity in tarot didn’t start to rise until after World War II, long after he was dead; Lovecraft was not given to esoteric knowledge of card games; and his few occult-minded friends such as E. Hoffmann Price and William Lumley do not appear to have had any knowledge of tarot, or at least none is mentioned.

At the same time, we can be fairly certain that Lovecraft was aware that tarot existed, and that cartomancy was a form of divination. Lovecraft had read Lévi’s History of Magic (translated by A. E. Waite), with its references to the tarot; he had also read fictional works like The Golem by Gustav Meyrink (translated by Madge Pemberton), which includes its tarot scene. So it is reasonable to assume that Lovecraft was at least vaguely aware of tarot, its purported occult history, and their use in both games and divination. Certainly, Lovecraft may have been thinking of tarot when he wrote:

One day a caravan of strange wanderers from the South entered the narrow cobbled streets of Ulthar. Dark wanderers they were, and unlike the other roving folk who passed through the village twice every year. In the market-place they told fortunes for silver, […]

—H. P. Lovecraft, “The Cats of Ulthar”

Yet this could also have meant palm-reading, or some other form of divination. Lovecraft may have known little solid about tarot until fairly late in life: there is no direct reference to tarot in his early articles attacking astrology, or his outline for The Cancer of Superstition, a book he had planned to write for Harry Houdini, but which was scuttled by the magician’s death. Weird Tales did advertise books of cartomancy, but most of these would have used a standard playing card deck, not tarot.

Weird Tales May 1935

It is doubtful that Lovecraft would have any strong belief in either the occult history of the tarot, and no belief at all in its value in divination. He was, as the he mentioned to fan Nils Frome in 1937, not a believer in fortune-telling; too much the mechanist materialist. Nor, for all that he read up somewhat on occultism, does Lovecraft appear to have been generally aware of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn or Crowley’s system of Thelema—which is understandable; Lovecraft was no more an occultist than he was a card player.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein uses Amazon Associate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.