I have a manuscript that almost beats yours. This is “In the Gulfs of N’Logh” by Hazel Heald. Besides that I’ve got an old poem of Lovecraft’s and another Hazel Heald story. The first story by Heald is composed of Thirty-two typewritten sheets.

—John Weir to Willis Conover, 16 Mar 1937, MSS. John Hay Library

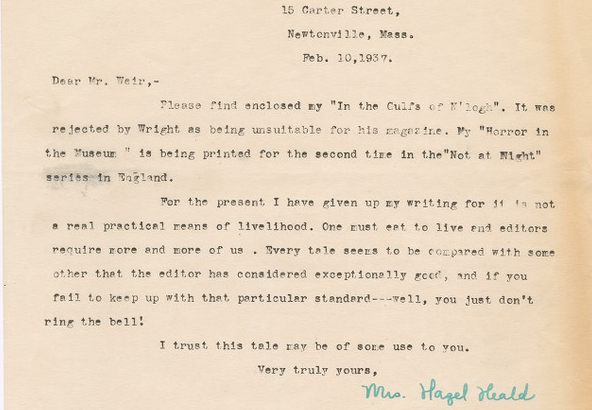

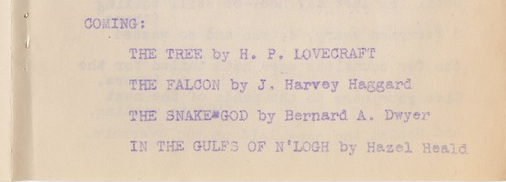

In January 1937, H. P. Lovecraft recommended that John T. Weir solicit material for his new fanzine Fantasmagoria from several of his correspondents, and specifically mentioned his former revision client Hazel Heald, whom he knew had a couple of unpublished manuscripts still in her possession.

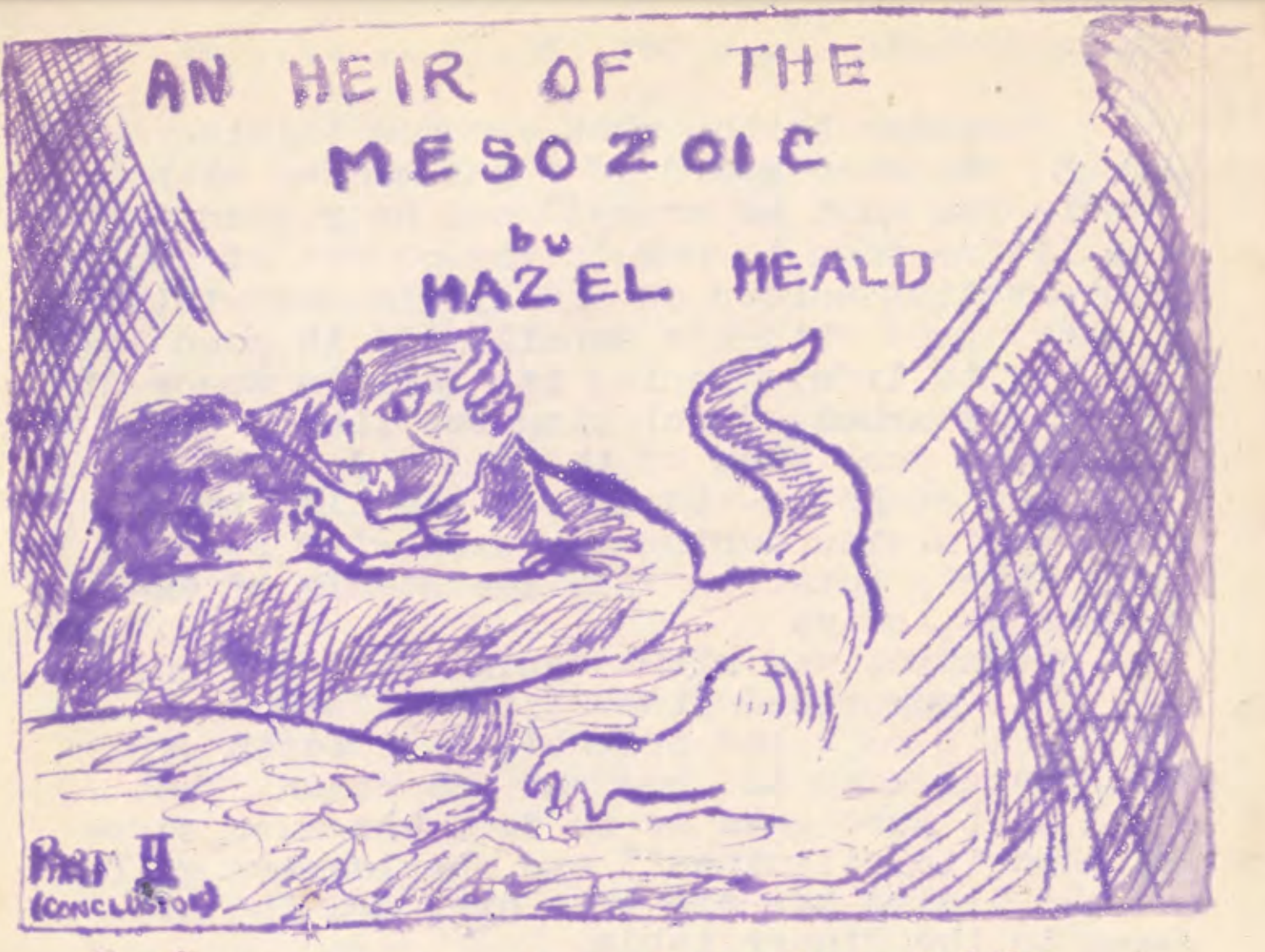

Hazel Heald responded by sending Weir two substantial manuscripts, “In the Gulf of N’Logh” and “An Heir of the Mesozoic.” While “In the Gulf of N’Logh” was too long for Weir to publish, he managed to split “An Heir of the Mesozoic” and publish it across two different issues—which, because of the vagaries of fan publishing, occurred a year after Heald had first submitted the story, and it was two years before the whole thing was published. So much time went by that Heald apparently became confused as to the details of the publication.

I have had several rejected tales I passed on to J. James Weird who is starting a new fan magazine. HPL advised me to keep myself in the public eye as much as possible.

—Hazel Heald to August Derleth, 31 May 1937, MSS. Wisconsin Historical Society

Several years ago a man wrote to me and said he would like some of my unpublished tales for a book he was going to publish, and though he did not pay for them, it would be good advertising. I did not regard them as worth printing, but he insisted. I even forgot his name and thought no more about it until I received a letter saying they would be printed soon. From that day to this I have heard nothing. Do you think he was trying to get plots for stories, and went about it in that way? I did not care anything about the tales as I have carbon copies somewhere, but it seemed like a strange request, didn’t it?

—Hazel Heald to August Derleth, 14 Oct 1944, MSS. Wisconsin Historical Society

Heald had written two letters to Weir asking about the publication in 1937, but she either never heard back or had forgotten this by 1944; it doesn’t seem likely she ever got a chance to see what would be her final story in print—and it has remained out of print since that publication, despite the fact that it was never copyrighted and has been in the public domain since Weir published it. While a few fans speculated that this might be a relatively unknown Lovecraft revision, the rarity of issues of Fantasmagoria prevented most from making any kind of judgment…until now.

The First Fandom Experience, whose outstanding publications include the Visual History of Science Fiction Fandom and facsimiles reproductions of the important early fanzines Science Fiction Digest and Fantasy Magazine were gracious enough to provide scans of “An Heir of the Mesozoic.” The scans have been uploaded to the Internet Archive and can be seen here. However, because the print quality of those early ‘zines was particularly poor, what follows before the review itself is a transcript of the text. A couple of sentences have become illegible over the decades of handling, but the bulk of the story is intact. Corrections and illegible portions are denoted by brackets [e.g].

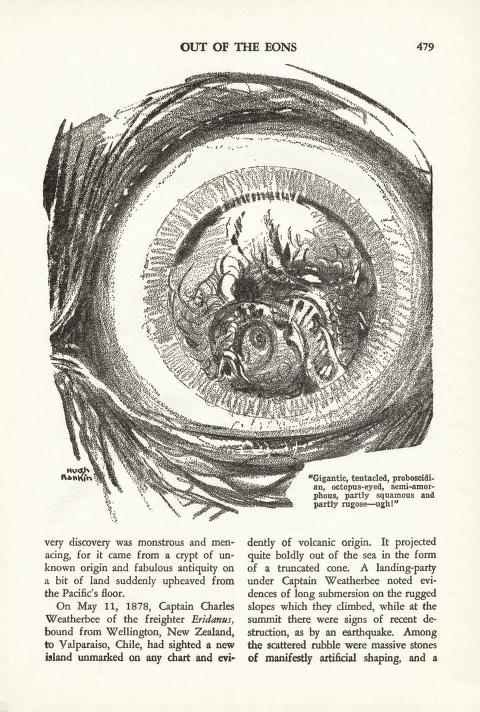

An Heir of the Mesozoic

by Hazel Heald

[Part I]

“So—Burt gave you this measly little thing. Quite a gift from a former admirer, I’ll say!” and Warren Drake looked quizzically at the little creature, half crawling, half-swimming around in the large crystal bowl in the center of the table. “What does he think we want of a salamander?” and he gave vicious poke with his pencil at the saurian, which resulted in a vicious snap from the little jaws. His wife, Veronica, pall’d at his arm and looked at her husband in a half-pleading way.

“Now Warren, leave the poor little thing alone. It’s mine, and I’m NOT going to let you tantalize it. Take something your size instead of that poor little helpless thing—such a mite—” and she switched indignantly from the room leaving her husband in a puzzled frame of mind.

“Helpless, eh?” ejaculated Warren, watching the knife-like tail slash the water, the little snake-like head lifted, with its bright eyes staring into his vehemently. Why the creature seemed almost human! Giving a last look, he left the room to make peace with his wife; who was now [illegible] only two short years before, after much competition with Burt Strout for her affections. Burt had taken it rather hard at the time for it had been a toss-up between them, but finally Veronica had decided in Warren’s favor. When the day of the wedding arrived, Burt drew Warren aside for a few minutes of private conversation.

“Warren,” he said, “In a few minutes you and Veronica will be made one, but I warn you now I will never entirely give her up, even if it is only in my dreams. If it hadn’t been for you, I would have been the lucky man waiting at the altar. And I will always be waiting for her—no matter how interminable the length of time. And when you turn up your toes for the last time, and the lily is placed on your breast, I won’t be shedding any crocodile tears. So you see, Warren, I’ve come clean, and am not hiding my true feelings from you. Be good to her or you’ll hear from me!” and Burt walked away, leaving a rather bewildered Warren.

Since then Veronica had received mysterious packages on special occasions like Christmas and Birthdays, but these always contained trivial gifts that could not be interpreted other wise than friendly offerings. Still it rather rankled in Warren’s consciousness and several rather bitter quarrels with Veronica had been the result. These, he felt, had been communicated to Burt in some way—it almost seemed as if a powerful wireless ran between their two selves. Perhaps he did say rather cruel and aggravating things to Veronica, but Nature had provided him with a rather vile temper, that when aroused, stopped at nothing. There was always a reconciliation and an aftermath to this weakness, but each was a little slower about coming about than the time before.

Burt had dropped in very frequently the first year of their married life, then his interest seemed to dwindle and his visits became rare indeed. but the last few months his lost interest had seemed to rekindle, only the night before he had brought the little dark brown specimen, half-lizard, half-frog, its only color being its spotted vermilion-red belly—thus starting the unpleasantness.

All the next day Warren seemed haunted with a stron[g] intuition of impending evil, as if a vandal had entered his home. Why should a little creature like a salamander fill his thoughts, driving all of the serious perplexities of his office work from him? He would get rid of it—accidentally tip the bowl over, then his heel could do the rest. The sooner it was done the better—Veronica wouldn’t mistrust but what it was accidental. And she might get more attached to the thing as time went on—then it would be more difficult to exterminate it.

So Warren went home that night with a fixed purpose in his mind. Veronica did not meet him at the door as usual, which rather surprised him, but her contagious laughter floated out from the living room to his ears, then a low rumbling voice gave evidence of a visitor. Entering the room he beheld Veronica sitting in a wingback chair with Burt standing in back of her, his arms resting on the back of the chair, while they both were indulging in a heart laugh.

“Why, hello, Warren—Ronnie and I were having a good laugh at your expense. So you didn’t like little Sally, did you? She’s like all the female of the species—more deadly than the male! But you’l like her in time, only don’t feed her too much—she might grow!” and Burt glanced at Warren with a look hard to analyze.

“Don’t lose any sleep worrying about me, Burt. I guess I’ll live through it. But I don’t guarantee that ‘Sally’ will. No little runt of a lizard will bother me long. You and Veronica are having a great laugh about nothing. What if I do abhor slimy things—that’s my business, and that thing crawling over the house isn’t a pleasing spectacle. Gorman has a couple of them always getting out—sometimes he find them crawling on his pillow, for he keeps them in a bowl on a stand near a bed. But you don’t catch me standing that—” and Warren slumped into a chair viciously sweeping a gray tabby-cat from its depths.

“Oh, did I rub your fur the wrong way?” questioned Burt. “I didn’t know I was touching a sore spot. you must be getting old if you can’t stand a little kidding. Ronnie just told me how Sally snapped at you last night. Anyone would think that the little hing had you worried. Better leave her alone—she might be a ticklish customer to handle if she returned to type—” and Burt gave a knowing wink, that was returned with an icy stare.

“Say, you tow, stop that silly scrapping and come to dinner. It will be getting cold,” and Veronica lead the way to the dining-room. An uneventful evening followed, with much bandying of words between Burt and Warren, the former’s conversation seemed to run on a tantalizing string. After a late goodnight he left reluctantly.

“Whew, I’m glad that pest is gone,” said Warren drawing a long sigh of relief. “Two nights in succession is enough to provoke a saint. now I want you to just scrap that friendship with Bert—just forget he rushed you once. As for that salamander—the sewer will be getting her soon—” and he stamped off to bed, leaving irate Veronica to nurse her wrath.

The next morning he arose with an aching head[,] acid stomach, and a general rundown feeling. Even his usual cup of strong coffee did not help, and the sleeping Veronica was mute evidence of last night’s quarrel, for she was usually up bright and early to prepare the morning meal. Glancing up at him with half-closed eyes from its crystal palace, the little saurian lay, its paddling arms crooked at the elbows like a human’s, its four fingers spread fanwise, while the five-toed hind feet were waving gently to keep the small body afloat. Warren could not resist poking it, but drew his fingers away as the little jaws rose to the [illegible] had teeth?

Each night Warren ascertained to kill the loathsome creature, but something always prevented. When he would draw his chair toward the table to read by the table lamp he would feel the little snaky eyes looking at him from their glass prison until he was forced to turn his eyes in their direction. Then the baleful look he was forced meet seemed to hypnotize him—until he was compelled to return to another room, or give up reading. Veronica would watch the scene with a knowing look but not offering any solution to his problem. Anyway, they weren’t too friendly these days—and she seemed to hover like a guardian angle over her pet. Confound the thing—it must be some spawn of the devil! The vicious jabs aimed at the thing when she happened to be absent were many, but they never found their mark. One favorite was a long, old fashioned hat-pin, which he held like a spear, but it never seemed to reach its [mark]. Some day—some day when the little [illegible] saurian got a good puncture his life would become normal again.

At last he decided to ignore the thing entirely, to [f]orget its existence if possible. So for a fortnight he persistently avoided the table where the bowl rested, although he could feel the creature’s eyes boring like gimlets, trying to draw his own in their direction. Then it came—the shock that made his hair rise on his scalp—his blood to run cold. On going past the table one night he looked into the crystal depths to find the saurian resting on a pile of rocks in one corner, its size being increased by one-half! It couldn’t be possible—Veronica must have been feeding it too many flies—or it was an optical illusion. Nothing could grow as swiftly as that in so short a time. But Veronica’s non-committal answers weren’t very enlightening—well, women weren’t very observing anyway!

[Part II]

That night he studied the lizard-like creature under a strong magnifying class, although its repulsiveness jarred on his already shattered nerves. It returned his stares unflinchingly, raising its flat head above the surface of the water, its beady eyes looking into his unwaveringly, the red mouth opening from time to time as if to gnash the imaginary teeth of its ancestors, while the vermilion and black spots underneath glowed with an evil light. The tough skin seemed to be stretched to its greatest extent, and the length of the human-like arms and legs had increased. It seemed to be more vicious than ever—trying to scale the slippery sides of the bowl to get at him.

For another week he kept away from the creature, for the sight of it repulsed and sickened him. Then one night at the dinner table Veronica startled him by saying, “Sally is beginning to cut her teeth. I wonder if they are milk teeth or wisdom? Burt thinks it’s a good joke!”

“Cutting teeth—what are you talking about! Who ever heard of a salamander with teeth—you must be crazy!” and he rushed into the living-room to behold the object of their conversation asleep on his little rock-island. A sharp prod with his pencil made it come instantly to life, opening its jaws in anger at being disturbed, disclosing two little white points on each side of the upper jaw which were unmistakably—teeth! It had also increased in size during the week—its hide fairly bursting with the strain of extended capacity.

Veronica was right behind him, looking at his surprised discomfiture. “Wasn’t I right, big boy? And probably more teeth will come later—and see how she has grown. That food that Burt gave me to feed her must surely have its vitamins!” and she laughed gaily as she linked her arm into his, drawing him back to the dinner table.

After this it was a regular occurrence to be informed that “Sally has a new tooth” or “Sally got out today and I found her under your bed.” All there was to it he must get rid of the pest! One night Veronica went out to a nearby theater to see a special feature, but Warren pleaded a headache. Now was his chance while she was absent to fulfill his plans!

Stealing softly into the room he tip-toed over to the table without turning on a light. He must not awaken the thing for it might be dangerous with all of its mysterious teeth. The bowl seemed extra heavy as he staggered out to the kitchen where he had laid out the ice-pick, hammer and various other tools. The lights shining in from the street made a dim twilight in which to work. Somehow in his over-cautious haste the bowl slipped form his hands into the soapstone sink with a splintering crash, followed by the thrashing of its occupant. Warren’s heart stood still—why it sounded as though the thing weighed pounds! Rushing to the center of the room he pulled the electric light cord, but an empty click was the only result. Confound it all, someone must have removed the bulb to plug in the electric iron and forgotten to have put it back!

A dull splashing in the sink was followed by a sharp thud on the floor as some object it it with a resounding clatter—then a slithering sound on the smooth linoleum gave evidence that the thing was still alive. Warren ran half-stumbling, half-running into the living-room, feeling nervously in the dark for the light switch—at last locating it with trembling fingers, but as before only an empty click was the result. From room to room he staggered, bumping into heavy furniture, scraping the skin from his tortured limbs—each switch being found useless. What could have happened to all of the lights? Something was wrong somewhere. A hurried glance out of the window showed the streets in darkness. A short circuit somewhere must have suddenly plunged the city into darkness! The black devils of all evil seemed leagued with that slimy thing somewhere in the depths of his apartment.

Suddenly, a bright idea penetrated his fear-crazed mind. The creature couldn’t have followed him as far as the bedroom he now occupied—he would just close the door and stay barricaded against its unpleasant presence. It might be inferior in intelligence and size, but those sharp teeth would not offer a pleasin[g] conclusion to his night’s adventure. And Veronica must never find out about this—she would jeer at his cowardice. Sliding over to the door he shut it with a bang that vouched for its staying closed for some time, then locating the bed he tried to make himself as comfortable as possible in its depths, with both ears straining for the slightest sound.

Why had he tormented the little saurian as he had? But it had always seemed to taunt him—its snaky eyes looking defiantly into his as if to draw him on. And to think of the size of the mammal-eating monsters it had descended from! Just lately he hadn’t bothered to even look at it. No knowing how big the creature was now. Anyway it gave a good thud when it landed, and that spelled danger with a capital “D”. And the bowl had seemed larger than usual. Good Heavens had it outgrown the other? This was no trifling matter, for it was unnatural for it to grow as it had. What could be the darn stuff that Burt gave Veronica to feed it? Well, that was an idea—he must inquire tomorrow—there was something fishy somewhere. And Veronica had such a fondness for the thing—almost silly at times. No, it couldn’t be any plot hatched between them although he had said he would never give her up. Strange words to tell a bridegroom! Had had seemed to drop around afternoons quite a bit lately—but anyway, he would take a few winks of sleep before Veronica came. The creature would not harm her—she petted it too much. As for absence of lights—she would speak to him quickly enough when she arrived, for she was a regular child in the dark.

No sound broke the stillness, and presently Warren took off his shoes and crawled in to bed fully dressed. The thing wasn’t in the room or it would have been thrashing around before this after being so long out of water. Probably it was a lot of nonsense anyway to imagine it knew him from anyone else. But how could he explain about the shattered bowl to Veronica?? He could say he was giving it a fresh lot of water—that would be the best explanation. It did not matter if he hadn’t done this before—the always was a first time to everything. it was no use trying to carry out any murderous designs on the creature in the darkness—it was a cinch it would get him first. As his nerves calmed down and the absolute silence of the place deadened his nerves, his eyelids drooped over aching eyeballs, and he was fast asleep.

How long he slept he did not know. Phantoms of the wildest sort flitted through his dreams, culminating in the leap of a monstrous gargoyle toward him as he lay trapped in a cave. When he started awake in a cold perspiration, some obscure instinct threw him into an attitude of intense and agonized listening—though for what he could not tell. Finally he thought he heard a sound—something like scraping of slippery feet over a polished floor. Before he could form a definite image his blood ran cold. Then he knew that this could mean only one thing. After all—in spite of all his confidence—that accursed saurian must be in the room! The utter horror of his helplessness made him draw himself farther under the bedclothes, pulling the quilts over his head. He felt cowardly lying here like this—but what could he do? A man couldn’t fight in the dark—and surely the creature could not get on the bed. If he could only see to kill it. It must be nearly time for Veronica—he must stall it off until then.

He couldn’t have slept long—but these beastly Fall evenings were interminable! The air was becoming stifling—he must get a few gasps, so cautiously removing his head from the covers he gulped it in filling his lungs in great sweeps—but both ears on the alert for any sound. A slight slithering sound near the window renewed his fears—the thing was moving around in a blind search for him! Slowly, noiselessly, eh reached for one of his shoes he had place[d] on the bed near the foot—then taking a careful aim he threw it in the direction of the weird sounds. A crash—then the sound of the thrashing of the thing as if in agony gave evidence that he hit his mark. At last the horrible sounds ceased, and Warren lay back on the bed, the beads of icy sweat making his forehead clammy and cold. He must have killed the thing after all! What a relief after this siege of horror! His hair would be white after this or he’d miss his guess! Now he would lie there until Veronica came—then the lighting system might be restored.

At last he dropped into a troubled sleep, filled with all sorts of prehistoric monsters, dancing in a circle around him, making his head swim with eternal whirling—their avid mouths full of long white teeth—their red tongues dripping with the blood of their victims. The circle was closing in on him—they were crushing his bones, sapping his consciousness—killing him……………

He opened his eyes, the horror of his dream overwhelming him—pulling the covers from his face for air. Then he screamed in terror as a snake-like head reared itself from a loathsome body that was lying full-length on his—eyes like gimle[t]s bored into his in the darkness, lit by a phosphorescent glow—the spicy odor of the saurian filling his nostrils with its loathsomeness. He tried to sit up, to throw the thing from his chest, but the evil jaws snapped at him, getting nearer and neare[r] to his throat. Its hot fetid breath fanned his face, the teeth gnashing in rage, while the blood that was flowing from its wounds, drenched the bedclothes.

His hands clawed at the thing[,] trying to pull it away, but the vicious jaws snapped at his index finger, sinking almost to the bone. The pain from the wound was terrific, he kicked, tore at the humanlike arms and fingers, and screamed desperately for help—but it was useless. The red mouth at last found its mark, the sharp teeth tore at his throat, and windpipe and jugular vein were severed in the hideous gnawing that followed. Then in a spasm of demoniac rage, the little four-fingered hands ripped his staring eyes from their sockets, while the hind feet kicked at his chest till the flesh was a mere pulp of gory laceration. But the creature’s own wounds were gaining on it. The vindictive tearings grew feebler—and at last, with a human-like sob, the grotesque monster sprawled inert—a lifeless lump of hideousness.

When the lights came on a frightful scene would have disclosed to any watcher—a scene in which a man and an abnormally overgrown lizard lay broken and blood-soaked in the grip of relentless death. But there was no one to watch—for hours passed before the hideous discovery was made. The papers dwelt on the horror but no inquest was thought necessary. Everything was so obvious.

But across the city, in a trim flat in Maple Street, the lights had revealed another scene as they flashed on—a scene which might have interested many persons both official and unofficial. There were a man and a woman—the former cool and self-satisfied, the latter white and shaken. The man was coaching and reassuring the woman, and promising great happiness to repay her for something she was going through. He was telling her how superficial the notion of conscience is, and urging her not to be frightened by what she would sooner or later have to face. And he was carefully explaining the glandular extract which, fed to man or reptile, stimulates the processes of abnormal growth.

THE END

“An Heir to the Mesozoic” does not appear to be a lost Lovecraft revision. Perhaps he had seen and commented on it at some point, and perhaps even Heald had submitted it to Weird Tales or Amazing Stories and it had been turned down; both magazines have published material on about this level. It notably contains no reference to Lovecraft’s Mythos, but then neither did Heald’s “The Horror in the Burying Ground” (1937); however unlike that story, none of the personal or place names, or even any of the prose, seem to show any similarities to Lovecraft’s style.

The reference at the end to “glandular extract” marks this as a particular mode of early science fiction known as “gland stories,” based on biochemical discoveries about the effects of hormones on the body (which would lead, eventually, to the production of synthetic hormones, making everything from birth control pills to hormone replacement therapy possible. But in the 1920s and 30s, “glands” were also the domain of noted medical frauds such as Serge Voronoff, who grafted monkey testicles to male patients promising restored virility, and John R. Brinkley, who promised miraculous effects from grafting goat testicles. In the domain of science fiction, glands could achieve almost any effect. An example of such as story is “The Superman of Dr. Jukes” (Wonder Stories Nov 1931) by Francis Flagg, one of Lovecraft’s pulpster peers and correspondents.

Other than that, there’s not a lot else to say. Like “The Man of Stone” (1932), there is a romantic triangle at the heart of this story, and a supernatural/super-scientific resolution. If this was more typical of Heald’s output outside of Lovecraft’s influence, it might explain why she had difficulty getting acceptance in the pulps: the plot isn’t bad, but it is basic; the prose doesn’t exactly sing or grip the reader; and the weird-science angle is a bit weak…despite the title, the unknown reptile never really hits “Age of Reptiles” levels.

Even if “An Heir to the Mesozoic” isn’t a lost Lovecraftian classic, it is still a rare weird story from one of Lovecraft’s revision clients. For those who wonder whether Hazel Heald could write, or what she would write outside of Lovecraft’s revision or ghostwriting—well, here we have an answer to that.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard & Others (2019) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014).

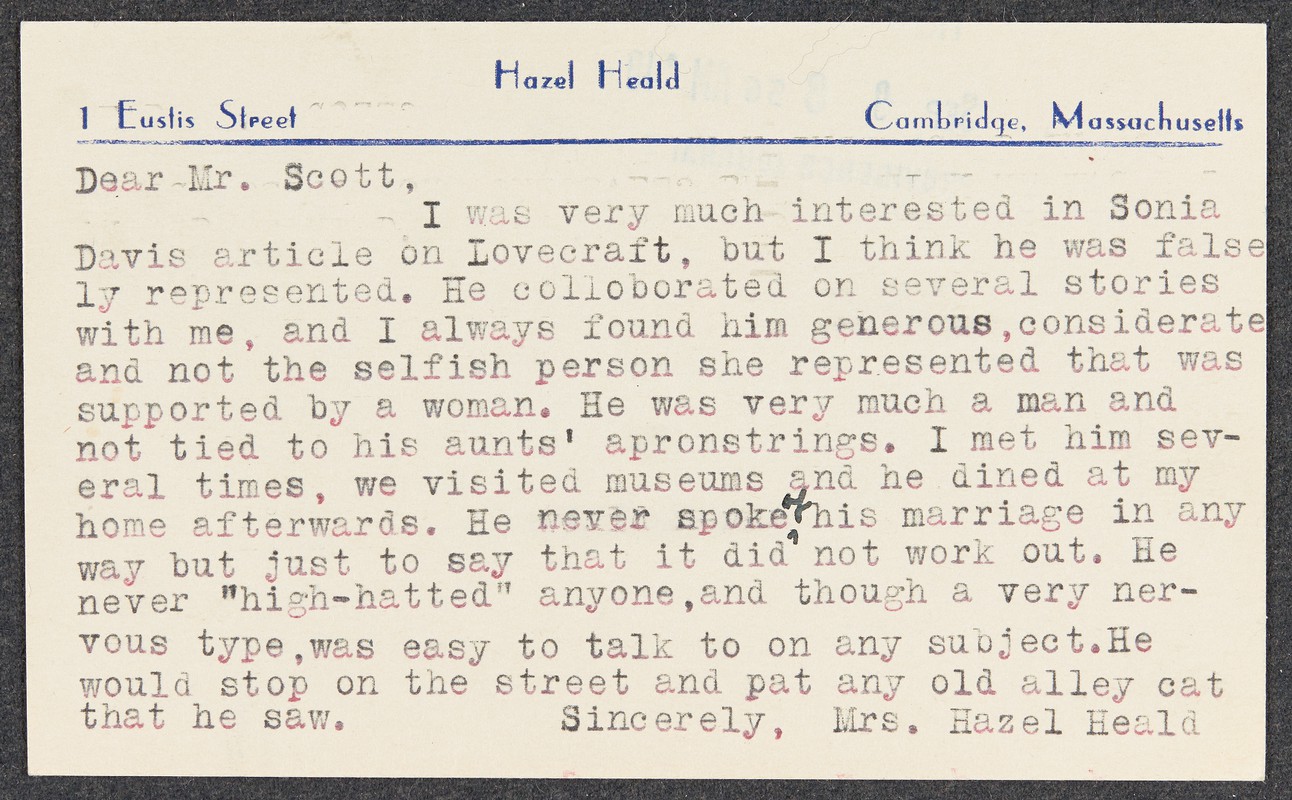

Hazel Heald to Winfield Townley Scott, 8 Sep 1948,

Hazel Heald to Winfield Townley Scott, 8 Sep 1948,