À Suivre (“To Be Continued”, 1978-1997) was one of the major Franco-Belgian comic magazines of the period, publishing such great European comics creators as Alexandro Jodorowsky, Milo Manara, Mœbius (Jean Giraud), François Schuiten, and Guido Crepax, a contemporary of magazines like Métal hurlant and Pilote, focusing on comics for a more mature audience.

“R. H. B,” by Andreas (Andreas Martens) and Rivière (François Rivière) was published in À Suivre 6-7, the July-August double issue for 1978. The title stands for Robert Hayward Barlow, friend and literary executor to H. P. Lovecraft. This coincides with the increased enthusiasm for Lovecraft in France, particularly the publication of LETTRES, 1 (1914-1926), which was published May 1978—a translation of Lovecraft’s letters, taken from volume I and part of volume II of Arkham House’s five-volume Selected Letters series. By comparison, Métal hurlant‘s Lovecraft special issue was published in September 1978.

H. P. Lovecraft received a fan letter from a 13-year-old R. H. Barlow in June 1931; Lovecraft was then 41 years old, and the two continued corresponding for six years, until Lovecraft’s death in 1937. The two met in May 1934, when Lovecraft took a trip down to Barlow’s family home in DeLand, Florida, a visit which lasted seven weeks; they met again briefly in New York during the winter of 1934-1935, where Lovecraft was in the habit of meeting friends for New Years Eve, and Lovecraft repeated his trip to visit the Barlows in Florida in 1935, where he spent ten weeks with his hosts, but begged off the invitation to stay all summer. Their next visit was when Barlow came to visit Lovecraft in Providence, Rhode Island, 28 July 1936, when the teenager stayed more than a month at the boarding house behind Lovecraft’s residence. It was the last time the two would meet; Lovecraft would die of cancer on 15 March 1937. Lovecraft’s “Instructions in Case of Decease,” dating from 1936, named Barlow his literary executor…and it is through Barlow’s efforts that many of Lovecraft’s papers, unpublished stories, and letters were preserved at the John Hay Library.

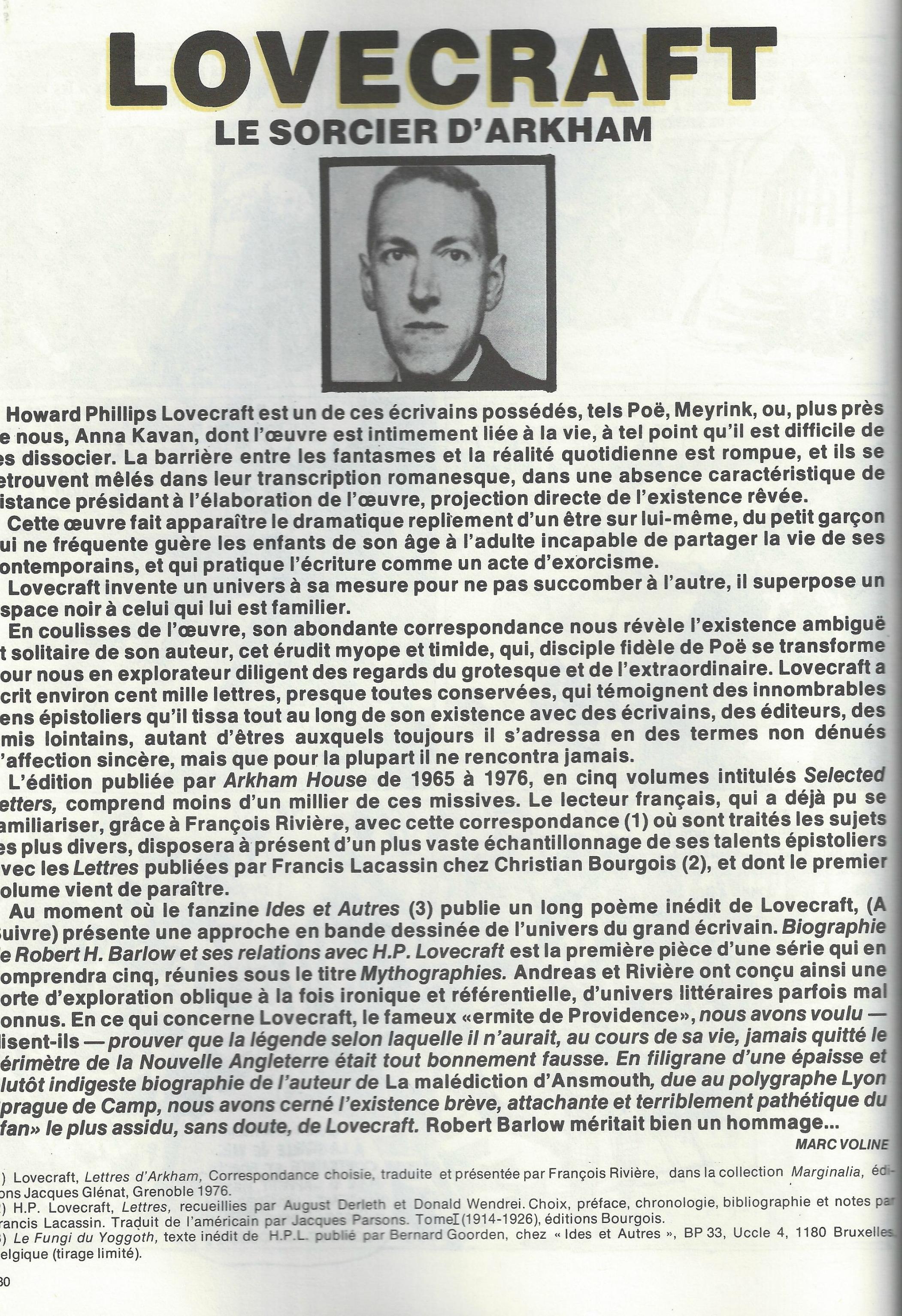

The comic proper is presaged by an introduction by editor Marc Voline:

At the time the Ides et Autres (“Ides and Others”) fanzine published an unpublished poem by Lovecraft (3), (A Suivre) presents a comic strip approach of the great writer universe. “Biography of Robert H. Barlow and his relationship with HP Lovecraft” is the first of a five-part series, collected under the title Mythographies. Andreas and Rivière designed this as a kind of oblique exploration, referential and ironic, of sometimes poorly known literary universe. As for Lovecraft the famous “hermit of Providence,” we wanted—they say—to prove that the legend that he would, during his life, never leaves the perimeter of New England was all simply false. From the thick and rather indigestible biography of the author of La malediction d’Ansmouth (“The Shadow over Innsmouth”) written by Lyon Sprague de Camp, we briefly identify with the existence of an endearing and terribly pathetic “fan” most assiduous without doubt Lovecraft. Robert Barlow well deserved homage …

Marc Voline

Most of the material in the comic would come from L. Sprague de Camp’s H. P. Lovecraft: A Biography (1975); this would not be available in French until 1987 when Richard D. Nolane translated it as H. P. Lovecraft ; le Roman de sa Vie, so the creators of “R. H. B.” were working through some linguistic hurdles and miscommunications. As Lettres 1 doesn’t have any actual letters from Barlow, essentially all of the material for “R. H. B.” was drawn directly from de Camp’s book, with many phrases translated directly from the English edition.

Small issues of translation aside, this is a starkly beautiful comic, with fantastic linework by Andreas, who obviously referenced what photos of Lovecraft were available. Translation of the French above:

Robert’s is not a happy family. There are frequent conflicts between him and his father, who suffers from depression (he is paranoid and continually fears the coming of improbable enemies.) Bernice, the wife of the colonel, spoiled the only son and quarreled with his father.

In spring 1934, Robert makes a profit of the absence of his father to invite Lovecraft to De Land. In April this year, HPL makes this journey. Lovecraft, in contact with the hot climate of Florida, is in an unusual state. He presents himself to Barlow with hatless and coatless.

His first stay in the house of his admirer is as a dream thanks to Bobby, he will see for the first and last time in his life a river full of alligators, at Silver Springs!

By comparison, this is how de Camp described this encounter:

The family home was at De Land, Florida, seventeen miles inland from Daytona Beach. Barlow’s father, Everett D. Barlow, was a retired U. S. Army lieutenant colonel and something of a mental case. Subject to moods of intense depression, he suffered from delusions of having to defend his home against the attacks of a mysterious Them. He was cracked on religion and on sex.

Robert Barlow got on badly with his father. At this time, he told his friends that he hated the colonel; although later, after his parents had been divorced, he carried on a friendly correspondence with him. Robert Barlow’s mother, Bernice Barlow, spoiled and pampered her son (somewhat as Lovecraft’s mother had done with him) and quarreled with her husband over the boy’s upbringing.

In the spring of 1934, Barlow and his mother were at De Land while the father, in the North, recuperated with relatives from one of his attacks. In January, Robert Barlow began urging Lovecraft to come for a visit to Florida. By April, Lovecraft had planned the trip. […] At the Barlows’, the heat stimulated Lovecraft. In high spirits he went hatless and coatless and boasted of the tan he was working up. His one disappointment was in not being able to go on to Havana. He was consoled by a trip with the Barlows to Silver Springs. There he had his first view of a jungle-shaded tropical river and even glimpsed wild alligators.

—L. Sprague de Camp, H. P. Lovecraft: A Biography 393-394

There are some errors in de Camp’s portrayal, which were repeated by Rivière. Lt. Col. Everett D. Barlow had seen action during World War I, and may have suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder; Lovecraft was aware of the elder Barlow’s mental illness and was notably more sympathetic than de Camp:

I surely am sorry that your father remains under the weather psychologically. These depressed states may be troublesome to others, & may seem exasperating when coupled with good physical health, yet they are really every inch as painful & unavoidable as any other form of illness. The victim can’t help himself any more than a victim of indigestion or cardiac trouble can. The more we know of psychology, the less distinction we are able to make betwixt the functional disorders known as “mental” and “physical.”

—H. P. Lovecraft to R. H. Barlow, 10 April 1934, O Fortunate Floridian! 125

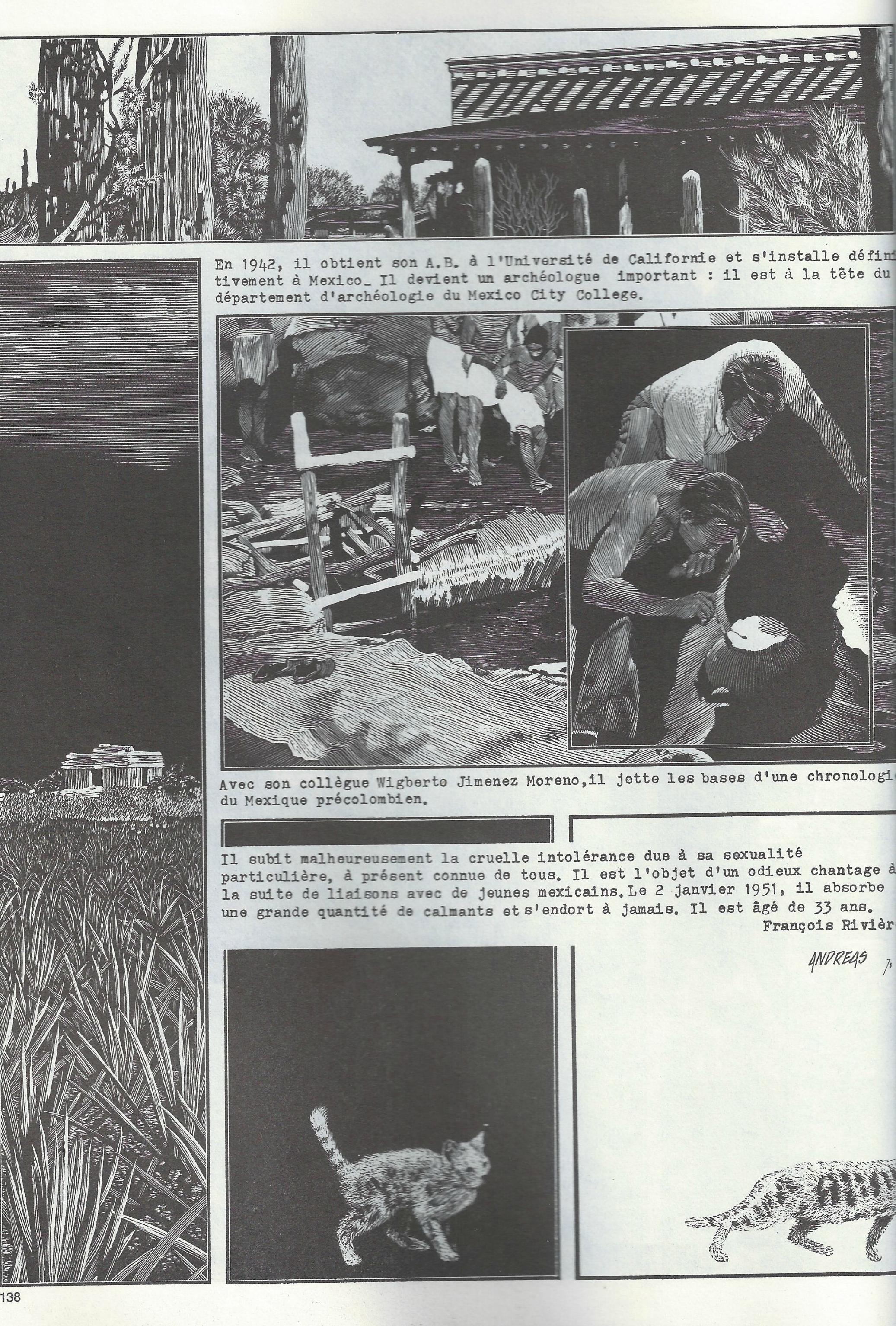

The narrative is, like most biographies, not some action-and-romance-packed account. Artist and writer manage to convey a sense time passing with the arrangement of the panels, particularly an extended shot of a kitten falling through perfect blackness that stretches out over several pages. While Lovecraft is the principal focus of the story because of the narrative, he dies in 1937…and Barlow’s story goes on, to his university education in Kansas, California, and then Mexico.

He unfortunately suffers the cruel intolerance due to his particular sexuality, at present known to all. It is the subject of an odious blackmail as a result of links with a Mexican youth. On 2 January 1951, it takes a large amount of sedatives and falls asleep forever. He is 33 years of age.

There are large parts of Barlow’s life that are not included in this brief but poignant bio-comic, because de Camp was more focused on those parts of Barlow’s life that concerned Lovecraft. We don’t read much about his career as a poet or writer of fiction; the issue of his sexuality and how de Camp came to publicize it was touched on in “The Night Ocean” (1936) by R. H. Barlow with H. P. Lovecraft, and here we see an example of how information spreads.

Notably absent from “R. H. B.” is an accurate depiction of R. H. Barlow himself. De Camp didn’t include any photographs in his biography for Andreas to base his depictions on, and few photos of Barlow at that point had been published.

c. 1935

Left to right: H. P. Lovecraft, R. H. Barlow, Bernice Barlow, unknown cat, Wayne Barlow

“R. H. B.” stands as an artistic achievement, and one of (if not the first) graphic adaptations of Lovecraft’s life to feature R. H. Barlow, who did so much to preserve his legacy. Others appear in Alan Moore & Jacen Burrow’s graphic novel Providence (2015-2017); Henrik Möller & Lars Krantz’s Vägan Till Necronomicon | Creation of the Necronomicon (2017); Sam Gafford & Jason Eckhardt’s Some Notes on a Nonentity (2017); and especially in Alex Nikolavitch, Gervasio, Carlos Aón, & Lara Lee’s H. P. Lovecraft: He Who Wrote in the Darkness: A Graphic Novel (2018), which showcases Lovecraft’s first encounter with Barlow in 1934…and all of these showcase how Barlow’s story has assumed its own mythical proportion, entwined with Lovecraft’s own.

While it was not uncommon for works in À Suivre to be reprinted, other than the publication in À Suivre, the only other publication of “R. H. B.” that I have been able to confirm is in The Cosmical Horror of H. P. Lovecraft: A Pictorial Anthology (1991), a tri-lingual guide to Lovecraft comics published up to that point, which reproduces six of the eight pages of “R. H. B.” and Révélations posthumes (1980), a collection of Rivière and Andreas’ biographical comics from À Suivre.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard & Others (2019) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014).

That brings back memories. I used to read “Wordt verfolgt”, the Flemish version of this magazine (Franco-Belgian comics were always published in both French and Flemish/Dutch) in the 1980s, though I never came across this particular strip.

LikeLike

I didn’t know there might have been a Flemish version! I’ll have to hunt for it to update my Dutch Mythos article.

LikeLike

I wasn’t a fan of the falling cat thing, it looked like unnecessary filler. 😦

Too bad that they didn’t know how Barlow looked like. His actual looks would fit the style of the comic really well.

Huh, I don’t remember him in Providence! It’s been a while since I read that comic. From your list I gather that he doesn’t appear that much in Some Notes on a Nonentity: The Life of H.P. Lovecraft?

LikeLike

The falling-cat thing is an artistic device that helps give a sense of motion and narrative progress in what is otherwise a bunch of still frames – sort of like the Ken Burns effect, where there’s a sense of motion even though nothing is actually happening.

Barlow is in SOME NOTES ON A NONENTITY for about two pages; Gafford and Eckhardt were a bit brisque on their association, but there’s a lot of that kind of thing that was mostly handled in Lovecraft’s correspondence and is hard to go through in detail. I simply forgot to add it to the list.

LikeLike