| Antarya traverse une crise des plus graves depuis que la reine Nawell a perdu la raison. Lors d’une trahison de haut vol, elle fait exécuter ses soldats. L’orc Kronan, capitaine de sa garde en réchappe. Pour lui, celle qui dit se nommer Nawell est une usurpatrice et il compte bien le prouver mais aussi se venger. Et quand Kronan se venge, il trace toujours un sillon de sang sur son chemin. | Antarya is going through a serious crisis since Queen Nawell lost her mind. In a high-level betrayal, she has her soldiers executed. The orc Kronan, captain of his guard, escapes. For him, the woman who says her name is Nawell is a usurper and he intends to prove it but also take revenge. And when Kronan takes revenge, he always leaves a trail of blood in his path. |

| Back cover copy for Orcs et Gobelins T11: Kronan | English translation |

The publication of J. R. R. Tolkien’s works The Hobbit (1937), The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955), and The Silmarillion (1977, with Christopher Tolkien and Guy Gavriel Kay) fundamentally changed the landscape of contemporary fantasy. Not just because of what J. R. R. Tolkien created and its enduring popularity, but because his approach to fantasy races and world-building set a high standard which many writers then took as a template for their own works. While Tolkien was not alone in creating fantasy worlds—Lord Dunsany’s The Gods of Pegāna (1905), E. R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros (1922), and Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword (1954) all preceded The Lord of the Rings—Tolkien’s conception of elves, dwarves, hobbits, ents, orcs, goblins, et al. strongly influenced the public imagination. This can especially be seen in tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons and Warhammer Fantasy, computer games inspired by those works such as World of Warcraft, and novels such as Dennis L. McKiernan’s Mithgar series.

Robert E. Howard’s fantasy in the pages Weird Tales in the 1920s and 30s represents a very different kind of fantasy. There are fewer distinct fantasy races in Howard’s work; there are no elves and goblins per se. The Children of the Night from “Worms of the Earth” (Weird Tales Nov 1932) and other tales are inspired by the Little People stories of Arthur Machen, but shaped by Howard’s correspondence with Lovecraft, have taken a very different form. They are not servants of a Satanic Morgoth or Sauron, nor are they corrupted elves or even inherently evil in a purely good-and-evil sense. The morality of Howard’s tales is always murkier, the racial politics more complicated, and that tarnished air, that hardboiled sensibility where there is no true good and evil, no ultimate victory for the forces of light or darkness, just men and women and things beyond human ken interacting according to their own needs and desires is part of what sets Howard’s fantasy distinctly apart from Tolkien.

Whether you call it sword & sorcery, heroic fantasy, or something else, Howard’s bloodier, grimier, but very approachable brand of fantasy had an equal influence with Tolkien on later writers. Tolkien may have helped define orcs, elves, and dwarves for a few generations, but Howard helped define the thief, barbarian, and mercenary man-at-arms as iconic roles. They both had their own contributions in terms of magic rings and magic swords, and they had a penchant for taverns and themes of kingship. While their ethos and style sometimes clash, their joint influence on fantasy is undeniable…and sometimes more strongly felt together.

In 2013, French comics publisher Soleil began producing a series of bandes dessinées: Elfes Tome 1: Le Crystal des Elfes Bleus was published in 2013, and became popular enough to become an ongoing series. These were set in a very generic Dungeons & Dragons-derived fantasy world called Arran. The series was popular enough to merit several spin-off series of various levels of popularity: Nains (Dwarves, 2015), Orcs & Gobelins (Orcs and Goblins, 2017), Mages (2019), Terres d’Ogon (Lands of Ogon, 2022), and Guerres d’Arran (Wars of Arran, 2023). As with D&D itself, this is very specifically riffing off of the popular conception of fantasy races derived from Tolkien, but the world is grimier, more visceral, a bit more hardboiled—Tolkien as filtered through Howard, in a sense.

Jean-Luc Istin is a veteran of the series, having written several of the preceding volumes of Elfes and Orcs & Gobelins, and for the 11th tome in the O&G series, he partnered up with Sébastien Grenier (artist) and J. Nanjan (colorist) to produce something kind of special: a re-telling of Robert E. Howard’s “A Witch Shall be Born” (Weird Tales December 1934) set in the world of Arran, and starring not Conan the Cimmerian, but Kronan the Orc.

Copyright law in France works a little differently than in the United States. During Robert E. Howard’s lifetime, the Berne Convention would guarantee his works would remain under copyright for at least 50 years after his death (since Howard died in 1936, that would mean 1986); in France, the general term is 70 years after the author’s death (i.e. 2006). Either way, Howard’s works are generally considered in the public domain in France (although international trademarks may still apply). Even if copyright was an issue, Kronan might still pass as an homage…but not a parody.

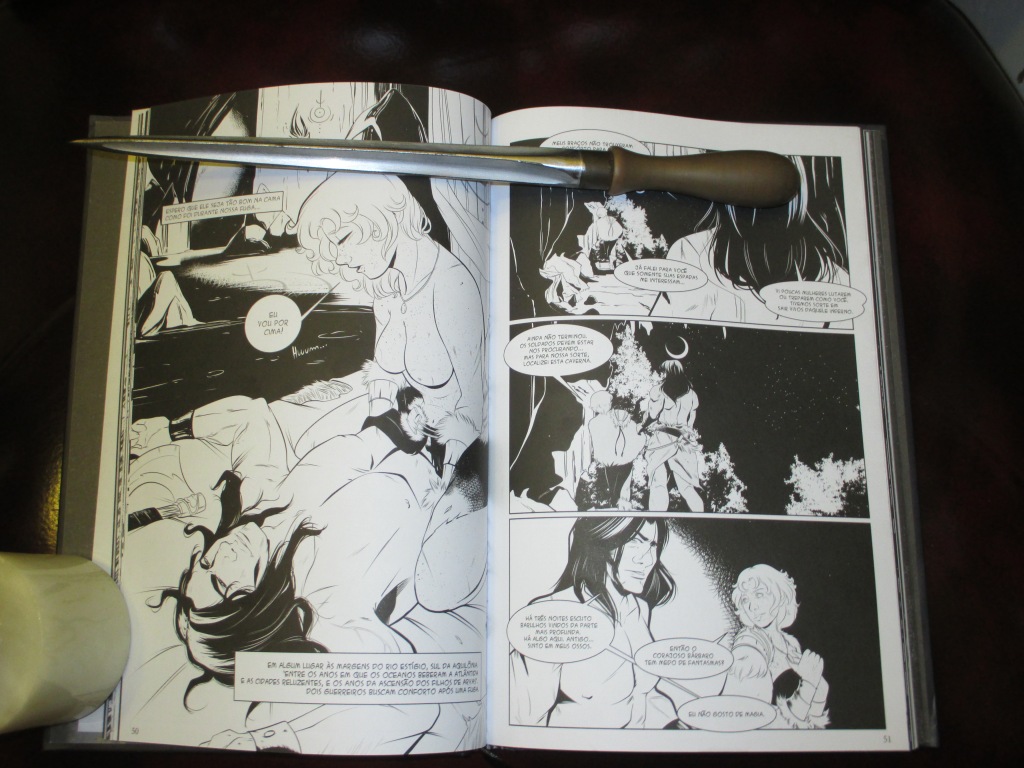

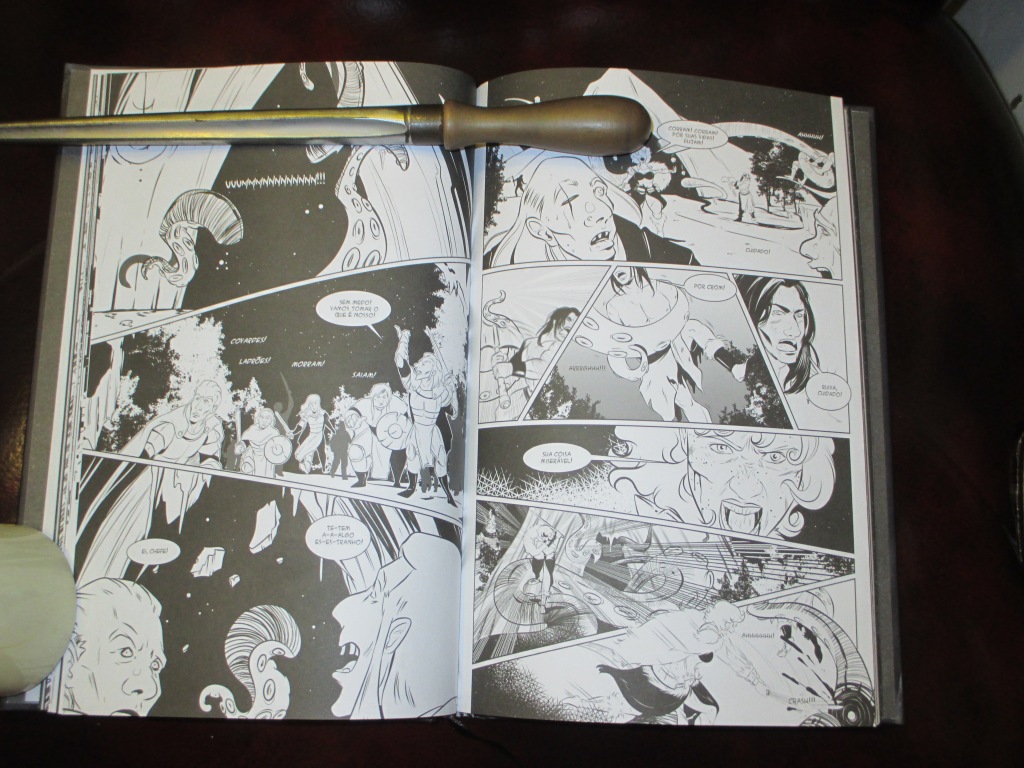

While the concept of Conan as an orc might sound silly, the creative team between Kronan plays it very straight. Kronan is a hulking, musclebound figure that takes very strong artistic influence from the fantasy bodybuilder culture that Frank Frazetta’s paperback covers, John Buscema’s comic book Conan for Marvel, and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s turn as Conan in Conan the Barbarian (1982) all helped to inspire, and readers can clearly see in the absolutely ripped muscles, the deep-set eyes, and long hair various influences from all three mashed together. Yet this is not just Conan with tusks and green face paint.

While Kronan follows the general outline of Howard’s story, and includes adaptations of many of the famous scenes—including Kronan on the cross, which was borrowed into the 1982 film—in adapting the story from Hyboria to Arran, the creators have shifted many of the details to fit the new setting. Instead of Crom, Kronan swears by the Orc deity Gor, for one example. In adapting the prose text to comic format, they’ve also veered away from some of the hallmarks of Howard’s narrative style in this story.

It is a weird penchant in Howard’s works that in several of the Conan stories, Conan himself takes a while to appear. The first chapter of “A Witch Shall Be Born” doesn’t mention Conan at all; it features Queen Taramis in her bed chamber, confronted by her twin sister. When Conan is first mentioned in chapter two, it is just that—a mention. The soldier Valerius is telling his sweetheart what happened. So we don’t actually see Conan in the story proper until he is crucified and on the cross.

In Kronan, by contrast, the narrative device is shifted: it is an older orc on a throne that is telling the story. We skip the bedroom scene with the queen (Nawell in place of Taramis) and see her attack her loyal army and citizens, and has Kronan crucified (as seen in a flashback-within-a-flashback). Where Howard had chapter 3 as a letter written to Nemedia about what all has happened, in the comic Kronan meets someone who tells him some these things, and we get a glimpse of Kronan doing some investigations of his own, breaking into a library to learn a bit of eldritch lore at knife-point.

Some aspects of the story are removed or simplified; we don’t actually see Kronan pull the nails out of his own flesh, as we did when Roy Thomas and John Buscema first adapted “A Witch Shall Be Born” to comics in Savage Sword of Conan #5 (1975); the crystal ball and acolyte by which the witch surveys the battle doesn’t feature either. Much of the architecture and landscaping is, for lack of a better term, more generically fantasy in aspect, with huge towers and walls, vast arched libraries carved into the solid earth, huge domed chambers like pagan cathedrals, etc. Arms and armor are likewise much more generic fantasy in design, less realistic than Howard’s descriptions, but more in keeping with the setting of Arran.

However, we do get some rather inspired artistic decisions. Kronan is the only Orc in the entire book, much as Conan was the only Cimmerian in Howard’s series; the one greenskin among a group of otherwise human characters makes him stand out all the more. Also, the occasional epic page-spread that really gives a sense of scale worthy of the series.

Taken together, the changes streamline the story and focus it more on Kronan himself. A lot of the exposition where a character talks about Conan become tales told to Kronan, or scenes that the reader sees directly; Kronan takes a more active and central role in unraveling the central mystery of the witch in the narrative, and there are fewer secondary characters to keep track of. The bones of Howard’s story are there, but Kronan is much more the focus, and the world is much more one familiar to gamers and Tolkienian fantasy fans than the Hyborian Age.

Yet for all that, it’s fun. There’s never been an adaptation quite like this, and never one that didn’t veer into winking at the reader or lapsing into parody, as when Mark Rogers adapted Howard’s Conan tale “Beyond the Black River” (Weird Tales May-Jun 1935) as “Beyond the Black Walnut” in The Adventures of Samurai Cat (1984). It is faithful to the mood and tone of Howard’s story, and Howard’s conception of Conan, while also making allowances for the different medium, the different setting, and the artistic allowance where a fantasy orc barbarian can ride a massive horned ox into battle while wielding a fifty-pound sword one-handed.

Perhaps needless to say, this is also fun. Sébastien Grenier’s art hits that sweet spot between the almost self-parody of Warhammer Fantasy and the more realistic tone or the Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition Player’s handbook. J. Nanjan’s coloring work is solid; while I might like to see what a black & white version looks like some day, the vividness of the colors used on the cover really makes the banners pop, and the use of light and darkness on the interiors in muted tones really works. I think a different colorist would have been tempted to make things brighter or darker, which would have ruined the effect and made the whole work much too cartoonish.

While the series has begun to be translated into English, Orcs & Gobelins Tome 11: Kronan is still available primarily in French.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein uses Amazon Associate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.