Am pulling out of a bad physical slump and have not done too much work, apart from the writing of poems in Spanish, some of which I hope to place sooner or later with Latin-American periodicals. They have been checked over by a good Spanish professor, who did not find too much to correct.

—Clark Ashton Smith to August Derleth, 31 March 1950, Selected Letters of Clark Ashton Smith 364

English was the language of Weird Tales during its first run (1923-1954), though stories might have snippets of any number of languages, natural, artificial, and fictional.

Neither H. P. Lovecraft nor Robert E. Howard were ever fluent in Spanish, though both of them were at least somewhat familiar with it. The evidence for Lovecraft’s knowledge is fairly slight: the two passages in his story “The Mound,” which had been ghostwritten for Zealia Brown Reed Bishop, both of which are largely accurate (the final portion was deliberately designed to appear somewhat crude); Lovecraft’s library included a copy of Ollendorff’s New Method of Learning to Read, Write, and Speak the Spanish Language (Lovecraft’s Library 139), which may have served him as a reference. Lovecraft also used Spanish openings and closings to some of his letters to Bernard Austin Dwyer in 1928 (during the period “The Mound” was written, and when Lovecraft recounted his dream of Roman Hispania), signing himself once “Luis Randolfo Cartero y Teobaldo” (LMM 468)

Robert E. Howard’s knowledge of Spanish was probably more utilitarian. In at least a casual way, he had picked up at least a small stock of Spanish and Mexican words—exclamations, terms of address, names of food and drink. Certainly, when Spanish-speaking characters appear in his stories their English dialogue tends to be sprinkled with a few choice Spanish terms, although sometimes with some peculiarities of spelling; a common technique when Howard wanted to express something of the rural or uneducated nature of the speaker, though it’s hard to tell sometimes if he is doing it on purpose or not, as he seems to have dropped this tendency in Spanish relatively quickly. So, for example, in “Red Shadows” (1928) he writes “Senhor,” in “Winner Take All” (1930) he writes “Senyor,” but in “The Horror from the Mound” (1932) he writes “Señor.”

In late 1948 or early 1949, Smith learned Spanish, made his first translations of Spanish poetry, and wrote his first poems in Spanish.

—Donald Sidney-Fryer, “A Memoir of Timeus Gaylord: reminsicences of Two Visits with Clark Ashton Smith, &c.” in The Romanticist #2 (1978) 3

Smith had already taught himself French from dictionaries and grammars in the 1920s; Lovecraft would praise his translations of Baudelaire. A decade after the death of Howard and Lovecraft, Smith would do the same with Spanish. All three men shared a love of language and poetry, and were autodidacts, but Smith was the only one of the three to attempt anything like fluency in Spanish, at least to the point of translating and composing poetry in that language.

His hopes of being published in that language do not appear to have been fulfilled during his lifetime, although some of his translations of Spanish poetry from Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, José A. Calcaño, and José Santos Chocano (“El Cantor de América”) did see print in zines and his poetry collections, and some of the English translations of his Spanish poems also appeared in his Arkham House poetry collections—including a translation or two of “Clérigo Herrero,” Smith’s Spanish pen-name (“Cleric Smith”—Clark, clerk, cleric).

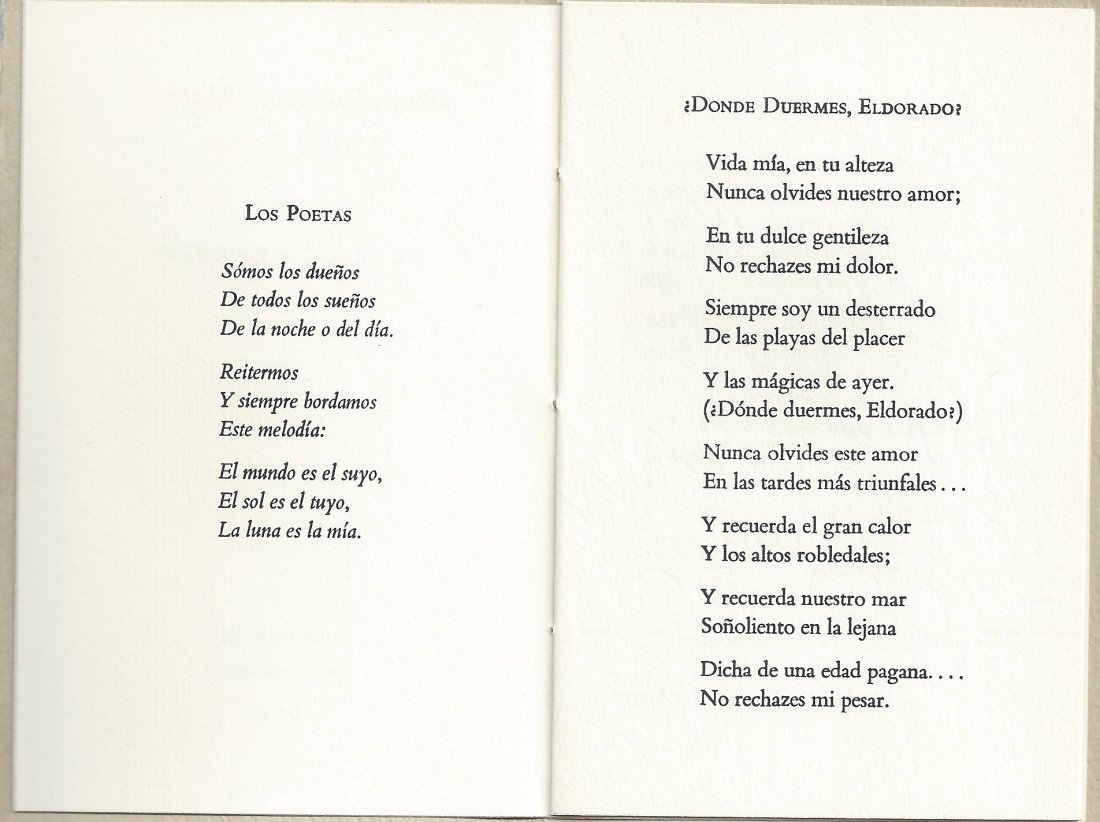

After Smith’s death in 1961, his widow attempted to continue to publish his work, and selling some of his letters and manuscripts in conjunction with letterpress printer and bookdealer Roy A. Squires. One of these projects was the small pamphlet ¿Donde Duermes, Elderado? Y Otros Poemas (1964), done entirely in Spanish, publishing eight of his poems as by Clérigo Herrero. The colophon says this printing was only 160 copies, although the bibliographies say 176.

Typescripts of some of his other Spanish poems, discovered after this printing, were published in Shadows Seen & Unseen (2007), showing something of his process:

For long decades, the Spanish poetry of Clark Ashton Smith was relatively unavailable: published far apart in limited editions. Today it has all been republished as part of the Collected Poetry and Translations of Clark Ashton Smith (2012) …and it is a testament to one of the great voices of Weird Tales to extend himself this way, to explore and express himself in another language. Because there is far more to this world than just the English language.

El mundo es el suyo,

El sol es el tuyo,

La luna es la mía.The world is yours,

The sun is thine,

The moon is mine.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard & Others (2019) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014).

Very interesting. I have greatly enjoyed learning about weird in translation. I would love to see if any other authors explored writing in second languages.

LikeLike

Wow, very impressive! I’ll have to check his Spanish works.

LikeLiked by 1 person