When Lovecraft began to hit his peaks in the late 1920s a young William Burroughs was cultivating a lifetime hatred of authority during his tenure at the Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico. In August 1931, teenage Bill could have gone to a news-stand in Los Alamos town and picked up the latest issue of Weird Tales, there to read about “the monstrous nuclear chaos beyond angled space which the Necronomicon had mercifully cloaked under the name of Azathoth” from Lovecraft’s ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’.

—John Coulthart, Architects of Fear

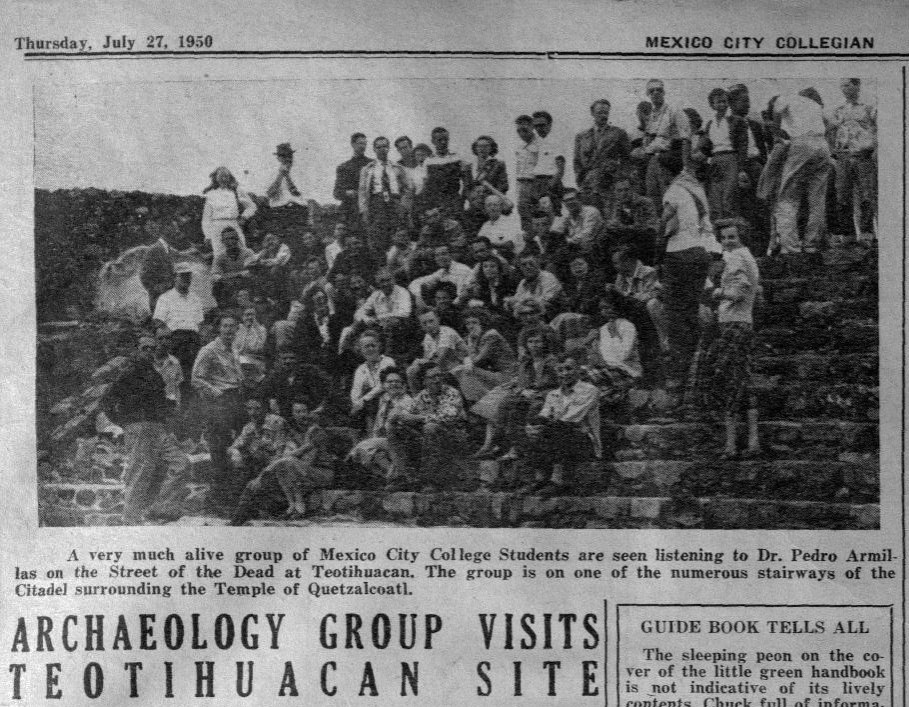

Thirteen years and change after Lovecraft’s death, in Mexico:

Somewhere in that grainy black-and-white photo are William S. Burroughs, who would become the godfather of the Beat generation and punk, and R. H. Barlow, the literary executor of H. P. Lovecraft. After Lovecraft’s death, Barlow had gone to university in Kansas City, MO and Berkeley, CA, before emigrating to Mexico in the 1940s. Barlow became an expert in Nahuatl and Mexica anthropology, a professor at Mexico City College, taught classes on Mayan codices and language.

Low tuition and cost of living combined with the G. I. Bill made Mexico City College a popular destination for American expatriates, including a young William S. Burroughs II, his wife Jean Vollmer, and their children. Burroughs studied the Mayan codices and mythology, suffered opiate withdrawal, experimented with orgone, and engaged in homosexual affairs. On the atmosphere of Mexico City, he remarked:

This is basically an oriental culture (80% Indian) where everyone has mastered the art of minding his own business. If a man wants to wear a monocle or carry a cane he does not hesitate to do it and no one gives him a second glance. Boys and young men walk down the street arm in arm and no one pays them any mind. It is not that people here don’t care what other’s think. It simply would not occur to a Mexican to expect criticism from a stranger, nor would it occur to anyone to criticize the behavior of others.

—William S. Burroughs to Allen Ginsberg, 1 May 1950, The Letters of William S. Burroughs: 1945 to 1959, 69

Despite Burroughs’ assertion, homophobia was still present in Mexico in the ’50s, and many homosexuals remained closeted. It is believed that fear of being “outed” may have been the reason behind the suicide of R. H. Barlow, who took an overdose of sleeping pills after a New Year’s Eve party ringing in 1951. Burroughs remarked:

A queer Professor from K.C., Mo., head of the Anthropology dept. here at M.C.C. where I collect my $75 per month, knocked himself off a few days ago with an overdose of goof balls. Vomit all over the bed. I can’t see this suicide kick.

—William S. Burroughs to Allen Ginsberg, 11 Jan 1951, ibid. 78

This was, as far as is known, the first of Burroughs’ brushes with things Lovecraftian.

The stay in Mexico City was short-lived. On 6 September 1951, Burroughs shot his wife Joan Vollmer in the head and killed her during a party. The children were sent back stateside to live with their grandparents, and after protracted legal proceedings, Burroughs left Mexico and was tried in absentia. Burroughs then spent several months traveling through South America, seeking out the drug yagé (ayahuasca), a fictionalized account of which was published as The Yage Letters (1963).

Burroughs’ writing became more experimental and nonlinear; Naked Lunch (1959) brought something like fame, as the book became the focus of an important 1966 obscenity case in the United States. He traveled: Rome, Tangiers, Paris, London. Mayan codices surfaced in his life again in London, as he sought to collaborate with artist Malcolm McNeill, even arranging to view the Dresden Codex at the British Library, for the work Ah Pook is Here. The complete work never quite came off, though both creators’ parts have been published since.

By 1974 he was back in the United States, in New York City—where just a few years later the Necronomicon by “Simon” was being put together at an occult bookstore called Magickal Childe. As Khem Caighan, the illustrator of the book, put it:

It was about that time that William Burroughs dropped by, having caught wind of a “Necronomicon” in the neighborhood. After going through the pages and a few lines of powder, he offered the comment that it was “good shit.” He might have meant the manuscript too—check out the “Invocation” on page xvii of his Cities of the Red Night. Humwawa, Pazuzu, and Kutulu are listed among the Usual Suspects.

—quoted in The Necronomicon Files 138

The success of the first hardback editions of the Simon Necronomicon gave way to a mass-market paperback. In 1978 Burroughs wrote an essay on this development “Some considerations on the paperback publication of the NECRONOMICON” (ibid. 139), where he said:

With some knowledge of the black arts from prolonged residence in Morocco, I have been surprised and at first shocked to find real secrets of courses and spells revealed in paperback publications for all to see and use. […] Is there not something skulking and cowardly about this Adept hiding in his magick circle and forcing demons to do the dirty jobs he is afraid to do himself, like some Mafia don behind bulletproof glass giving orders to his hitmen? Perhaps the Adept of the future will meet his demons face to face. (ibid)

As Dan Harms and John Wisdom Gonce III note in the Necronomicon Files, Burroughs fails to speak specifically about any edition of the Necronomicon in his essay, but the editors of the paperback edition truncated a quote from the essay and slapped in on the back book anyway. The full and unadulterated version they quote:

Let the secrets of the ages be revealed. This is the best assurance against such secrets being monopolized by vested interests for sordid and selfish ends. The publication of the NECRONOMICON may well be a landmark in the liberation of the human spirit. (ibid, 140)

All of these factors—drugs, homosexual experiences, Mayan codicology and mythology, death and violence, studies in the occult, and travels in South America, Africa, and Europe—came together in the experimental novel Cities of the Red Night (1981). Among those ingredients were Burroughs’ tangential brushes with things Lovecraftian. As Khem Caighan and Harms & Gonce note, the opening invocation to Cities is:

This book is dedicated to the Ancient Ones, to the Lord of Abominations, Humwawa, whose face is a mass of entrails, whose breath is the stench of dung and the perfume of death, Dark Angel of all that is excreted and sours, Lord of Decay, Lord of the Future, who rides on a whispering south wind, to Pazuzu, Lord of Fevers and Plagues, Dark Angel of the Four Winds with rotting genitals from which he howls through sharpened teeth over stricken cities, to Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned […] to Ah Pook, the Destroyer, to the Great Old One and the Star Beast, to Pan, God of Panic, to the nameless gods of dispersal and emptiness, to Hassan I Sabbah, Master of the Assassins.

To all the scribes and artists and practitioners of magic through whom these spirits have been manifested….

NOTHING IS TRUE. EVERYTHING IS PERMITTED.

—Cities of the Red Night xvii-xviii

Harms & Gonce have called Cities of the Red Night a “surrealistic tribute to pulp fiction,” and it may even be that. We know little of what pulps that Burroughs read, but we do know that he read them. The manuscripts for The Yage Letters mention True; Cities of the Red Night includes reference to Amazing Stories, Weird Tales, and Adventure Stories (329); The Place of Dead Roads (1983) includes a short but accurate summary of Frank Belknap Long Jr.’s “The Hounds of Tindalos” from Weird Tales. In one interview, Burroughs said:

I read Black Mask; I remember Weird Tales and Amazing Stories—there were some very good ones in there, and some of them I’ve never been able to find I used some of those in my own work, but I’d like to find the originals, but never could. Who was that guy [who wrote about] “the Old Ones”?

H. P. Lovecraft?

There was somebody else.

Arthuer Machen?

He was another one, too. But anyway, Lovecraft was quite good and earnest. This place right by the—it’s always New England—where there’s vile rural slums that stunk of fish because they’re these half-fish people! It was great.

—”William S. Burroughs: The Final Interview” in Burroughs and Friends: Lost Interviews 66

The book is nonlinear, bouncing back and forth between narratives that interconnect in odd ways, sharing characters, hinting at a bigger picture that never quite resolves. Burroughs had a skill for pulp-style genre fiction, but his greater talent lay in subverting readers’ expectations. Just when you think you know what is going on, the next chapter usually proves you wrong. Plot threads are laid down and then forgotten, or picked up a hundred pages later in a completely different context. The eponymous Cities of the Red Night are simultaneously physical locations that exist before all other human civilizations, places that can be visited, and spiritual stages in a journey of soul improvement.

If you had to give the whole text a label, “experimental novel” works as well as any. The book defies rational analysis because it defies conventions, full stop. The protagonists are almost exclusively violent and homosexual, the sexual situations graphic, genres blend together quickly and easily. Considerable chunks of the text are pure exposition, describing imaginary weapons, occult rites, the structure of a revolution that never happened, cities that didn’t exist, fantastic and impossible combinations of drugs and sexually transmitted diseases, conspiracy theories involving aliens and time travel, and complicated systems of reincarnation.

It is busy book, bursting with ideas and imagery, and quite lavishly indulges in breaking taboos. In many ways, Cities of the Red Night is a regurgitation of long-festering ideas and influences; chunks of the early book seem inspired by the Yage Letters, chunks of the later chapters from Ah Pook Is Here. Those who have read more of Burroughs’ earlier works may get more out of it than those who come in cold, but anyone expecting a trippy read that yet resolves itself into some kind of ongoing revelation a la Robert Anton Wilson’s The Eye in the Pyramid (1975) might want to brace themselves. The end of Cities of Red Night does not resolve; the plot threads are not tied up; characters and ideas are left where dropped, like a child’s playthings.

Maybe next book.

There were two more books, in what is generously defined as a “trilogy”: The Place of Dead Roads (1983) and The Western Lands (1987). There are some nominal connections between the stories, and a great many common themes, but as with Cities of the Red Night there is not really any sort of overarching plot. The scope and characters change, gunslingers in the Old West that seek escape into space, or away from death, and these things are tied together in different ways, but…they are books more suited to sortilege than casual entertainment.

They are also ugly. Burroughs’ sexual tastes at that point in his life were homosexual, and nearly all of the sexual encounters in the book are homosexual, which is fine and maybe to be expected—those squeamish about such things might consider what it is like for a homosexual man or woman to read a book that goes on at length about heterosexual encounters and how they might feel. Yet it is also true that many of the sexual encounters skew young, even to the point of pedophilia; this was noticeable in The Yage Letters and is hard to miss in Cities of the Red Night, which includes teenage prostitutes and sexually-active young boys. Female characters are almost absent, and those present often villainous or included solely for purposes of reproduction. At points in the trilogy this breaks out to straight misogyny where the characters hope to break free of women as essential for reproduction altogether.

Racism is prevalent, although a bit complicated. Burroughs’ protagonists are almost always white and male, like Burroughs himself. Stereotypes based on race and ethnicity are common, often exaggerated for comedic or scatological effect, and racial pejoratives aren’t uncommon. It’s unclear sometimes how much of this is Burroughs’ deliberate taboo-breaking and how much of it is just Burroughs’ own prejudice, the drug-addicted, homosexual gringo globetrotting the world, trying to keep one step ahead of the criminal convictions, carrying the remnants of early 20th century colonial attitudes with him where he went.

Is it Lovecraftian? Is anything of Burroughs? The Simon Necronomicon certainly had its influence, however small, on Cities of the Red Night and its sequels; The Place of Dead Roads has absorbed a chunk of “The Hounds of Tindalos” into its literary DNA. Burroughs even had a story published in a Lovecraftian anthology: “Wind Die. You Die. We Die.” (1968) appeared in The Starry Wisdom: A Tribute To H. P. Lovecraft (1994); it contains not one word in reference to the Mythos or Lovecraft. Yet Ramsey Campbell in the introduction to that book observed:

Burroughs has fun with pulp in very much the same way that Lovecraft parodied such stuff in his letters. (7)

Which is certainly true. Lovecraft and Burroughs were both working with some of the same building blocks—quite literally in the case of “The Hounds of Tindalos”—albeit to different purposes and with a vastly different sense of aesthetics. John Coulthart in his essay “Architects of Fear” draws this comparison as well, and says of Cities of the Red Night:

Burroughs’ cities are brothers to Lovecraft’s Nameless City, and to Irem, City of Pillars, described in ‘The Call of Cthulhu’ as the rumoured home of the Cthulhu Cult. The Cities of the Red Night are invoked with a litany of Barbarous Names, a paean to the “nameless Gods of dispersal and emptiness” that includes the Sumerian deities that Burroughs found catalogued in the ‘Urilia Text’ from the Avon Books Necronomicon, and which includes (how could it not?) “Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned.” In Burroughs work the ‘Lovecraftian’ is transmuted, the unspeakable becomes the spoken and the nameless is named at last, beneath the pitiless gaze of Burroughs’ own “mad Arab”, Hassan I Sabbah, Hashish Eater and Master of Assassins. “Nothing is true, everything is permitted.”

Burroughs remains one of the most influential postmodernist writers of the 20th century. Lovecraft, through however many degrees of contact, was an influence on Burroughs. Distinguishing between the shades of their joint influence on subsequent authors is like trying to put a crowbar under a fingernail to see what lies underneath. That is the creeping nature of literary influence; like one of Burroughs’ fictional viruses, it gets into almost everything, and often comes from unlikely sources at unexpected times.

You don’t have to have even read Lovecraft to be influenced by him.

Which is both a very Lovecraftian and a very Burroughsian thought.

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard & Others (2019) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014).

“Lovecraft is a virus…”

LikeLiked by 1 person

While you did a great job presenting the facts, reading all this about Burroughs makes me want to bathe in bleach…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cronenberg’s “Naked Lunch” captures some of the “Cities of the Red Night” horror vibe despite being a quasi-biographical film sourcing a different novel thought largely unfilmable.

LikeLike