Have you ever heard of the Necronomicon? No? That’s probably because you’ve led a normal life…a life in which that dreaded encyclopedia of evil has never entered…

The Thing #11 (Nov-Dec 1953), 18

1953. The war was over. On the magazine racks, brightly-colored comic books, eager to catch the eye and earn the dimes of children and adults alike. Romances, westerns, a scattering of super-heroes, crime, science fiction, and horror. The pulp magazines are dying, fewer of them on the stands every month, but the comic books are lurid and varied, each outfit competing with the other.

Charlton Comics was a latecomer to the field of horror comics. Their most notable entry was The Thing, a horror anthology comic consciously modeled on EC’s Tales from the Crypt, launched in February 1952 and lasted 17 issues, ending in November 1954; today most notable for the artistic talents of a young Steve Ditko in the later issues. Under the editorship of Al Fago, The Thing sought to distinguish itself in a crowded field with low page rates and relatively lax editorial oversight, with the hope this artistic freedom would provide solid stories and provocative artwork—and unfortunately for them, they succeeded in drawing attention to themselves, though not the kind they wanted. (The Charlton Companion 48, 52-4)

In The Thing #11, released in November 1953. “Beyond the Past” was a short comic in the middle of the issue, only 4 pages. Artist Lou Morales signed the first page, but the writer, letterer, etc. are uncredited, which was typical. Comics in the 50s were often churned out swiftly, in workshop fashion, and individual creators were not always credited. The other stories in the issue (and many issues before and after) were written by Carl Memling, and he may be responsible for the script on “Beyond the Past” as well.

The story itself is relatively direct and minor: an old professor studies the Necronomicon, mumbles an incantation (“Xnapantha..xnapnatha..Chrtlu..xmondii…”), and accidentally calls up that which he cannot put down. Lovecraft had many fans among the early horror comics, as evidenced by “Baby… It’s Cold Inside!” in Vault of Horror #17 (1951), and “Portrait of Death” (1952) in Weird Terror #1 (1952). For the most part, this would be classed as forgettable filler, but for two things.

For one, “Beyond the Past” is an early appearance of the Necronomicon in a comic book. For two, it caught the attention of Frederic Wertham, and became a footnote in the moral panic that led, ultimately, to the institution of the Comics Code Authority and the vanishing of horror comics from the shelves in the United States and other countries.

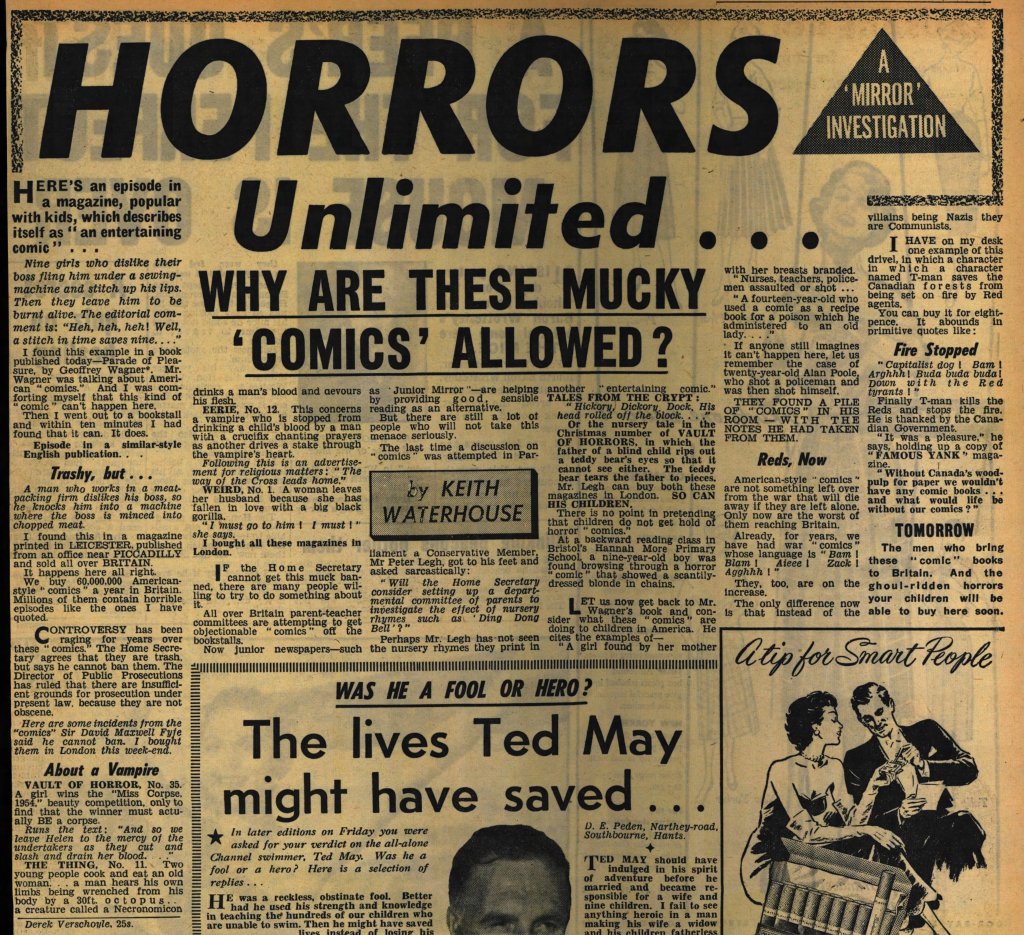

The Thing, No. 11. Two young people cook and eat an old woman. . . a man hears his own limbs being wrenched from his body by a 30ft. octopus . . a creature called a Necronomicon drinks a man’s blood and devours his flesh.

Keith Waterhouse, “Horrors Unlimited” in the London Daily Mirror, 13 September 1954

Nearly a year after The Thing #11 was first published, an article ran in the London Daily Mirror, decrying the comics that kids were buying these days. This was not exceptional; the United Kingdom had been undergoing its own moral panic about comic books, which would eventually result in the Children and Young Persons (Harmful Publications) Act, which was passed into law in 1955. For details see Martin Baker’s excellent A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign; see also John A. Lent (ed.)’s Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-Comics Campaign, which adds important detail.

Keith Waterhouse focused on imported American horror comics and described a handful of issues in a sensationalist style. Never mind the issues he rants about had likely been off the stands (in the United States, at least) for months; and that he could hardly have read them very carefully if he mistook the Necronomicon for the blood-thirsty monster Xnapantha the professor had summoned. No one was likely to fact-check him.

Someone in the United States, however, also read Waterhouse’s article.

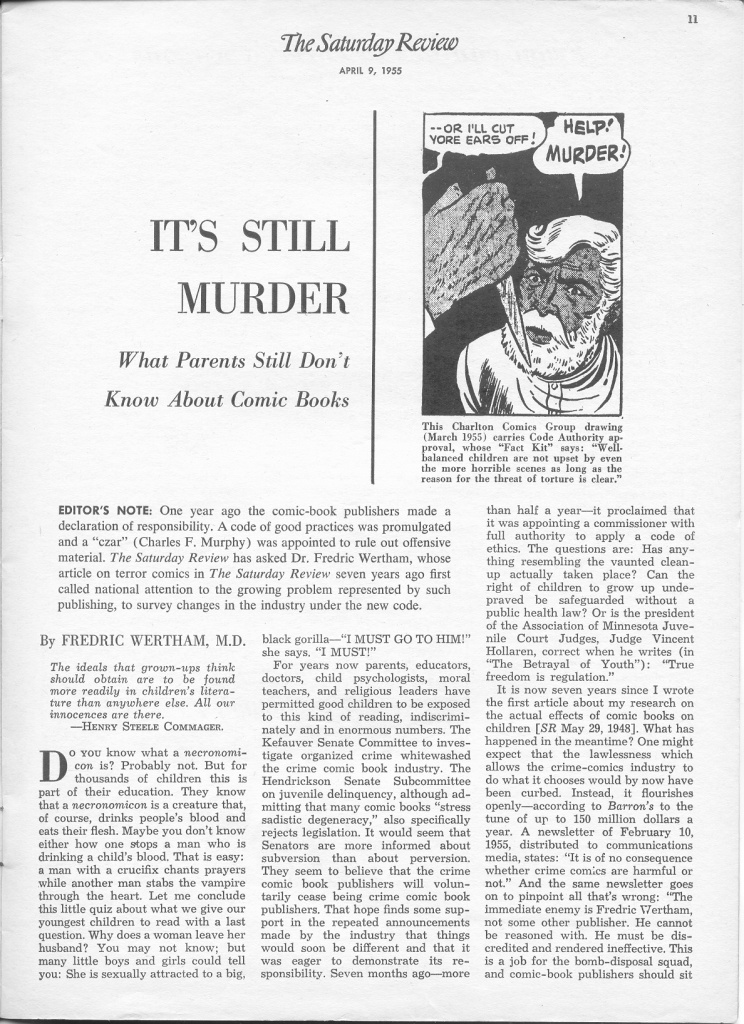

Do you know what a necronomicon is? Probably not. But for thousands of children this is part of their education. They know that a necronomicon is a creature that, of course, drinks people’s blood and eats their flesh.

Frederic Wertham, “It’s Still Murder” in the Saturday Review 9 April 1955, 11

By 1955, Wertham had won. In April 1954 his book Seduction of the Innocent had stirred a moral panic in the United States and abroad to the highest level, he testified before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in April and June, and in September the collective comic book publishers in the United States formed the Comics Code Authority, censoring themselves to stave off government interference. Crime and horror comics vanished from the newsstands, and would have a ripple effect around the world, starting similar moral panics in the United Kingdom and other countries.

Yet Wertham continued to campaign against the deleterious influence of comic books on the youth. Thanks to the research of Carol Tilley, we now know that Wertham faked his research, distorted facts and figures to match his narrative. What most folks don’t acknowledge is that Wertham didn’t stop. He certainly wasn’t above reusing Waterhouse’s garbled idea of what a Necronomicon was to his own benefit.

Wertham used the leading question about the Necronomicon more than once; a 1954 article titled “The curse of the comic books” appeared in the journal Religious Education Vol. 49, No. 6 a few months prior with essentially the same opening, and Wertham may have reused it elsewhere.

There is no surprise in this case that Wertham got the details wrong; there are numerous examples in Seduction of the Innocent where his apparent encyclopedic knowledge of comic characters and plots is shown to be superficial at best. What’s surprising is how he got ahold of a British newspaper article—possibly through a clipping service—and how swiftly and avidly he seized on the word Necronomicon, apparently in complete ignorance of its provenance.

Like a weird game of telephone, the misconception about the Necronomicon, now totally separated from its source material, continued to promulgate through the web of concerned citizens.

Dear Parents:

Isabelle P. Buckley, “Your Child” in the North Hollywood Valley Times, 22 Apr 1955, 11

“Do you know what a necronomicon is? Probably not.[“]

Buckley depended on Wertham’s integrity as a scholar; she took his article as fact as she clutched her metaphorical pearls and told parents to worry about what their kids might pick up down at the corner drug store or newspaper stand. Wertham depended on Waterhouse’s journalistic integrity, that the reporter had gotten his facts correct. Neither of them bothered to investigate for themselves, any more than Lou Morales picked up an Arkham House book to confirm whether it was supposed to be “Chrtlu” or “Cthulhu” in the incantation.

After all, who would notice?

“Beyond the Past,” like many of the stories from The Thing, has relished in relative obscurity. Now in the public domain, it was finally reprinted in Haunted Horror #25 (2016, IDW), and in rougher form in The Giant Readers Thing (2019, Gwandanaland Comics), but the whole story can be read for free at Comic Book Plus.

Addendum: A sharp-eyed reader pointed out that while this might be one of the earliest comic appearances of the Necronomicon by name, the story “Dr. Styx” in Treasure Comics #2 (Aug 1945) includes the writings of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred. Read G. W. Thomas’ article on the story here. The Necronomicon also featured in “The Black Arts” in Weird Fantasy #14 (Jul-Aug 1950).

Bobby Derie is the author of Weird Talers: Essays on Robert E. Howard and Others and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein uses Amazon Associate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Great post! While not discussing comic books, I wonder if the Wertham case inspired Sonia to write her essay, “Juvenile Delinquency”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure, but if it was written 1954-1955, then probably.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just looked and it was not. She gave a speech on Child Delinquency in May 1949, which obviously, her essay must’ve been written prior to the event.

LikeLike

Right. So that’s within the range of the beginnings of the anti-comics campaign, but probably not directly influenced by Wertham (although he had been publishing on the subject for years).

LikeLiked by 1 person

The thing is, in her essay, Sonia doesn’t entirely blame media for juvenile delinquency, but the parents, teachers, and authorities for not being proactive in correcting a child’s behavior.

LikeLike

Keith Waterhouse wasn’t as humorless as his article would make one think. After all, he did found the Association for the Abolition of the Aberrant Apostrophe.

LikeLike